Building with Music: Sound is a Spatial Force

Promises for the 1872 Jubilee.

Robin Sparkes September 4, 2025

Architecture and music offer distinct but interconnected ways of shaping space. A building’s design directs how sound travels, influencing what people hear, how intensely they perceive it, and the atmosphere it creates. Music, on the other hand, constructs space from within, manipulating acoustic variables in real time. From recording in a bedroom, singing in a karaoke bar, performing in a warehouse or amphitheater, music has the power to transform how a space feels and how we move within it. Just as light waves can brighten a room, sound waves shape the emotional and atmospheric essence of a space.

We can shape the reverberation and resonance of a room by carefully positioning sound sources to guide how the sound unfolds. Subwoofer arrays and delay stacks allow us to synchronize sound across different areas and control how far the bass travels. Using EQ and level adjustments, we can direct the listener’s focus, concentrating frequency similarly to light waves, like a beam of sunlight cutting through a window to illuminate a single point in space. Bodies in a crowd act as moving absorbers and diffusers, continually reshaping the sound field. Through rhythm and spatialized playback, we can influence how these people move and connect, making circulation itself a medium in the psychoacoustic design of space. Sound design, then, acts as a form of spatial agency, granting us the power to reshape the architecture around us in real time.

Music changes how a space feels, the beat drives the room, making it feel entirely different than it would in silence. Sound waves bounce off surfaces, enter the body, and shift perception. A static building hosts sound, and when music activates its acoustics, the architecture responds in real time, becoming embodied and alive. Sound can be a tool for restructuring architecture and redefining our relationship to the environments around us.

Reclaiming Space: Underground Music

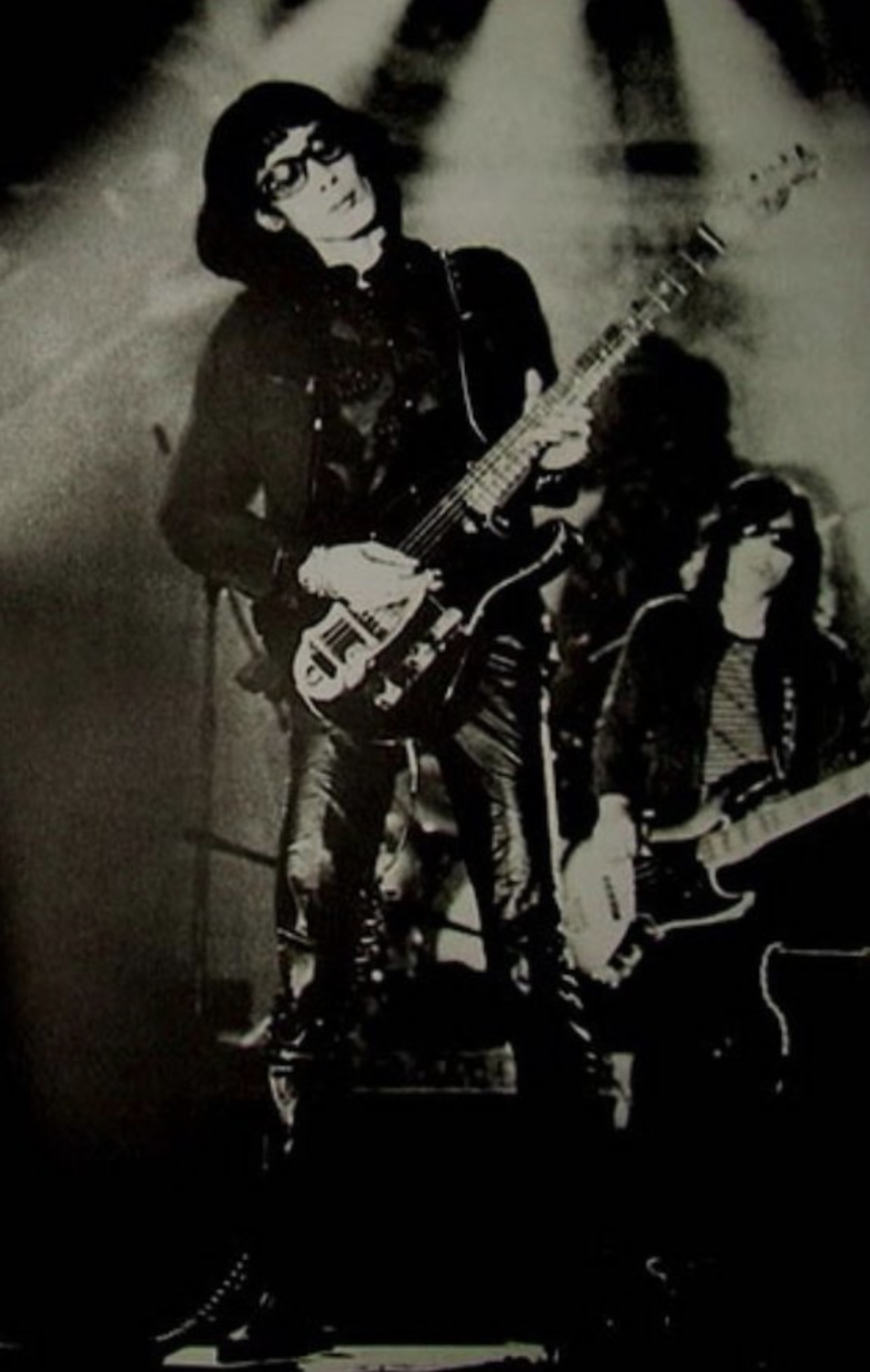

Les Rallizes Dénudés.

The acoustic elements of architecture often serve systems of bureaucracy and control. Underground music has the power to reclaim both historical and physical spatial narratives, turning architectural constraints into opportunities, transforming neutral or neglected spaces into sites of shared meaning and protest. By tuning into how music architects space through sound, we can engage in spatial activism to reaffirm presence, build community, and reimagine the built environment. Underground music reclaims space by asserting temporal agency, shaping how time is experienced and shared, and creating moments that resist permanence. A dance floor becomes a blueprint to reimagine the boundaries of time. The audience, moving as one, reshapes the space in real time.

Les Rallizes Dénudés, a psychedelic noise band that emerged in late 1960s Kyoto, were defined by their uncompromising use of volume and repetition in live performance. The only recordings they left behind came from these shows, where protest was enacted in real time and space. By rejecting mediated formats of releasing music, they made the audience’s presence inseparable from the music itself. Through this approach, Les Rallizes Dénudés transformed live performance into a spatial archive. Their music redefines agency by centering presence, activating space as part of the work itself, and imprinting sound directly into a collective experience.

In a similar way, through an evolving ensemble of musicians, performers, and visual artists, Parliament-Funkadelic activated space through collective rhythm. Working across Detroit, Washington D.C., and Philadelphia, they transformed venues into full sensory worlds. The Mothership was a structure of frequencies, basslines and layered harmonies constructing a space of communion.

George Clinton directed these experiences as both bandleader and maker of space. He expanded perception and invited participation into P-Funk's expansive sonic environments. In Good Thoughts, Bad Thoughts, Clinton offers a manifesto: “Every thought felt as true… blossoms sooner or later into an act and bears its own fruit.” In live performances Clinton points to a spatial principle of a “higher vibration”, where thought, sound, and growth are all forces that shape experience. His invocation of vibration echoes both acoustics and the metaphorical language of quantum theory, where energy and matter are understood as forms of oscillation.

Funkadelic used vibration to tune the room beyond the limits of sight. In Mothership Connection, Clinton’s chants and performances collapsed the boundary between artist and audience. As Gascia Ouzounian states, controlling sound is a way of controlling presence. P-Funk, however, designed presence as an open system—alive, communal, and bound together. This is the “higher vibration.

“Bowed fragments scrape into industrial resonance, while sustained tones blur into the hiss of air and the drone of engines. In this juxtaposition, nature and industry collide.”

In the early 1970s, Martin Rev and Alan Vega emerged from New York City's underground scene, pioneering a fusion of punk energy and electronic experimentation. Rev’s synthesizer, driven by an arpeggiator, generated a continuous cascade of notes, cycling through repeating patterns that created a hypnotic, trance-like effect, enveloping the audience. Rev’s drum machine pulsed with a heartbeat-like rhythm, imposing time on the audience while space seemed to collapse and expand around them. Vega’s presence on stage was commanding. His voice cut through the pulsating rhythm, turning individuals into subjects through the power of address, transforming the call into music itself and folding the audience into the performance. Through this hypnotic, repetitive beat, Rev and Vega cast spells over the spaces they performed in.

Reclaiming Space: Loud Sound

A Crowd Almost Dwarfed by Performers, National Peace Jubilee, Boston, June 1869.

Sound travels through the ear and floods the body with vibration. Depending on tone and frequency, it reflects, lingers, or presses against surfaces. Live performance can manipulate space through sound, creating environments where amplification and presence reorganize how bodies relate to one another. Tim Hecker expands this approach in his essay In the Era of Megaphonics (2007), tracing the rise of amplified sound from the 1880s onward. He examines how emerging technologies of the industrial revolution, such as megaphones, gramophones, and PA systems, transformed public address and performance. These tools shifted sound from embodied, proximate speech toward projected volume, redirecting attention from verbal meaning to sensory force. He situated this transformation within mass political rallies, religious revivals, and stadium-scale concert sites, in sound saturated space and intensified collective experience.

Amplification became a method for restructuring power relations, turning sound into an immersive field that conditioned behavior and expanded public presence. Distortion and amplification emerged as techniques for redrawing spatial experience. Hecker’s music practice and performances bring these principles to life, transforming venues into immersive soundscapes. His music employs deep drones, dissonant harmonies, and fluctuating frequencies to create a sense of vast, shifting space. Layered textures and industrial tones evoke tension and transcendence, while fog, darkness, and sustained sounds suspend time. In this way, Hecker sculpts space with sound, transforming the room into an instrument itself.

Reclaiming Space: Returning to Nature

Sound can trace the contours of the earth, bending industrial intensity toward the rhythms of wind, water, and foliage, shaping how we inhabit and feel the world around us. London-based artist Damsel Elysium’s music inhabits this intersection, weaving textures of industrial noise and the natural environment into sonic landscapes that reclaim both presence and place. Their work positions sound as a living medium, where body, space, and collective experience resonate together. Damsel reimagines the use of classical instruments, violin and cello, as tools for spatial experimentation. Beyond the traditional orchestral roles, these instruments become vehicles for evoking sounds of wind, machinery, and elemental textures. Bowed fragments scrape into industrial resonance, while sustained tones blur into the hiss of air and the drone of engines. In this juxtaposition, nature and industry collide.

Their performances extend beyond conventional venues into ritualistic encounters with natural environments. At Clandestino in Sweden, Damsel arranged flowers into a semicircle between themselves and the audience. The ritual culminated in the distribution of flowers to each participant, a gesture that carried the performance into the lives of the listeners. The ritual becomes a spatial act of reclamation, an invitation to experience the presence of nature together.

By blending the timbres of string instruments with industrial textures and natural soundscapes, Damsel activates a living dialogue between ecological memory and urban sound. Their work proposes new ways of feeling powerful in space through communion with the environment. Sonic environments, older than human architecture and music, remind us that sound has always been building the world around us.

Robin Sparkes, is a spatial designer, studying the kinesthetic experience of architecture. Her design, research, and writing practice traverses the relationship between the body, temporality, and the acoustics of space.