From Cynicism to Sincerity

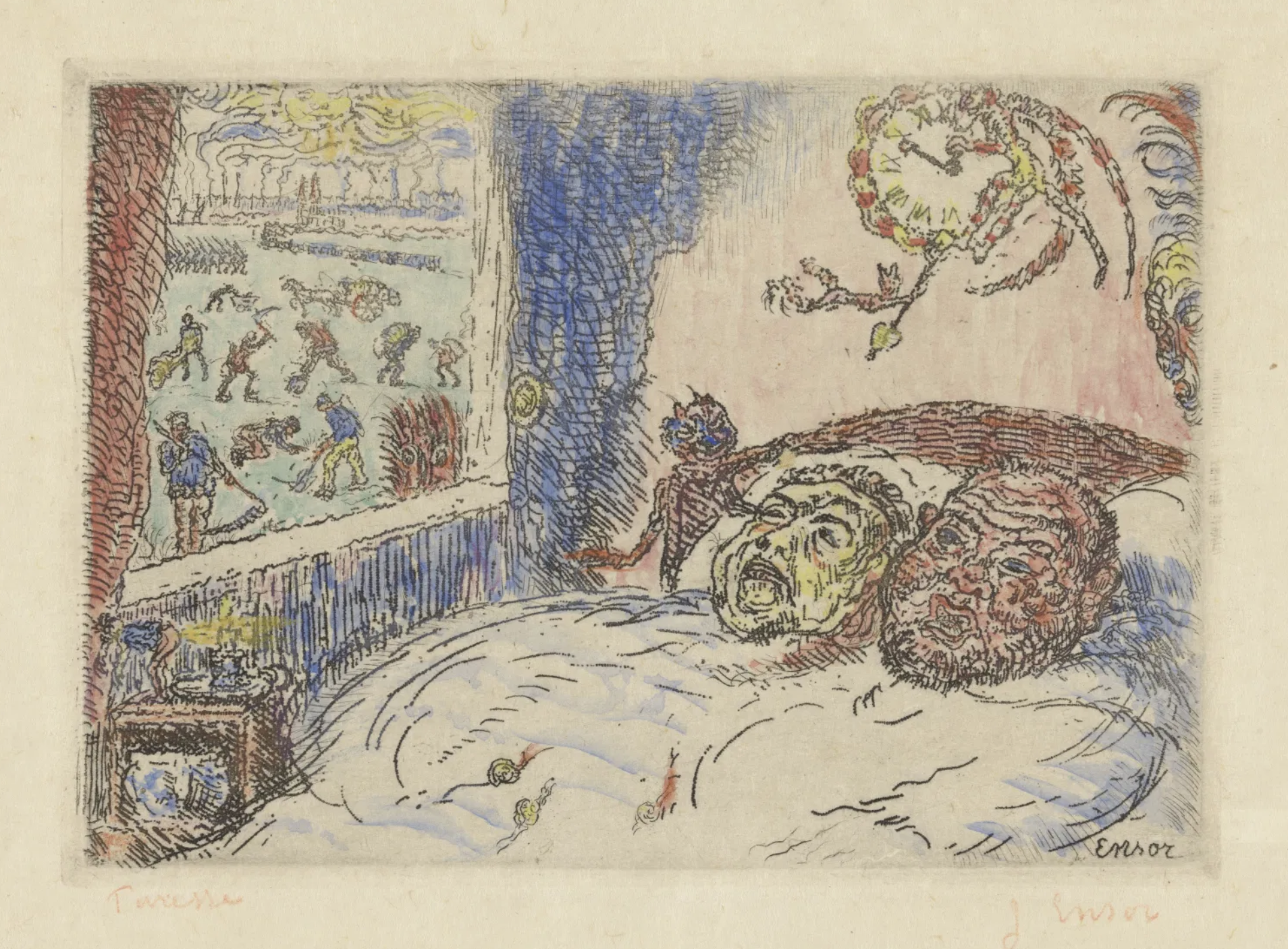

Sloth, James Esnor. 1904.

Noah Gabriel Martin January 27, 2026

The key feature of what I’ll call the 90s West Coast slacker accent is that the tone dips at the end of a phrase, like an inverse question. It doesn’t indicate conviction, however. Instead, the slacker tone is all about ironic detachment; it allows the speaker to say something while signalling that they don’t care about saying it, each claim a candy wrapper thoughtlessly dropped to the floor as they keep on walking.

The purpose of the slacker tone is to distance the speaker from what they’re saying, to show that they can’t be found in their words, that the things they say can’t be used to identify them, who they are, or how they feel. The arc of the pitch descends just as each sentence concludes, like a slash crossing it out as it tumbles off their tongue.

That’s not to say that what they’ve said isn’t true, or even that they don’t believe what they’re saying, just that what they’ve said doesn’t matter to them, and the fact that they’ve said it shouldn’t be taken to mean that that’s how they feel. In short, the slacker tone is a disclaimer that alienates sincerity.

Why say things if they don’t care about them? It’s a puzzle, but the greater mystery is why a whole generation might adopt a tone of voice contrived to undercut each expression, signaling that the things we say are of no importance and shouldn’t be taken seriously. What would motivate us to systematically undermine the power of our own speech?

The slacker tone of voice has frequently been conflated with sarcasm. In fact, the quintessential example of slacker voice is from a 1996 episode of the Simpsons - one punk says “Are you being sarcastic, dude?” to another, who responds “I don't even know anymore.” He doesn’t know, because he hasn’t decided to be sarcastic; to reject as false and even worthy of ridicule the position he’s aping. The slacker voice is more ambiguous than sarcasm, it doesn’t reject the thing being said, thereby actually taking an affirmative position contrary to it; it refuses to take any position at all. If sarcasm announces, with ridicule, that you don’t agree with the semantic content of what you’re saying, a slacker tone makes it impossible to tell what you believe in, or if you believe in anything at all.

The Simpsons’ calling attention to this voice is a distraction from the fact that this snark was the entire style of The Simpsons; the undecided, un-pin-downable position which disowns everything and affirms nothing was characteristic of its era, and The Simpson epitomised it. It treated the mainstream with irreverence, without actually taking up a position against it. It dismissed all seriousness as equally ridiculous, refusing to look at whether some positions might be more worthwhile than others.

The Marxist cultural critic Frederic Jameson, called this style of speech ‘pastiche’, and it was marked by a refusal to sign onto any political project and fight for it. He identified it with a postmodern rejection of commitment to the truth and value of any political cause. Jameson described the kind of parody that isn’t motivated by belief in something, exactly the kind of parody we see in The Simpsons, as ‘parody without a vocation’ or ‘parody with no target’ and nothing to defend. “It is a neutral practice of such mimicry”, he said, “without any of parody’s ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any conviction that alongside the abnormal tongue you have momentarily borrowed, some healthy linguistic normality still exists.”

Growing up as a precociously jaded teenager on the Westcoast, the freewheeling, mainstream, equal opportunity cynicism of The Simpsons was exciting. Maybe we didn’t need a programme; maybe it was enough to satirically lay waste to the corrupt pieties of earlier generations. I didn’t think the onus was on us to replace it with a platform of our own. In fact any positive ambition seemed arrogant; indulgence in the hubristic naivety of thinking you’ve got all the answers. The important thing didn’t seem to be to change things, the important thing was not to fall for the bullshit.

“The fear of being a dupe makes us stupid, because it gets in the way of our sensitivity to differences between more and less dangerous errors.”

What I didn’t understand then was how well this callow nihilism plays into the hands of the status quo. Established power is victorious by default, and the fight against it is an uphill battle. All that’s necessary for those in power to maintain their privilege is for nothing to change, they have inertia on their side. Cynicism, scepticism, and nihilism, even if it takes swipes at the status quo, always ultimately reinforces it.

To have a chance, the side of change needs to offer something. It’s not enough to destroy. To become real, the will to change must create.

That’s why, far from bringing down the system, the snarkiness of the 90s could only engender nastier and nastier iterations, from Family Guy to the Pepe and Soyjak memes on 4chan and 8kun image boards. Because it eschewed sincerity as “cringey” from the start, this caustic sense of humour could never give rise to hope. However, it could curdle into a politics that used jokes to conceal a very real lust for the free expression of cruelty and hatred.

90s slacker indifference also served a deeper political and social need: ego defense. Its linguistic detachment is there to protect the speaker. But to protect against what? What could pose so general a threat that any sincerity, no matter how righteous, would leave one open to it.

The American Pragmatist philosopher William James criticised undue skepticism as the ‘fear of being a dupe’.

The problem, according to James, with the ‘fear of being a dupe’, or what most philosophers would call ‘epistemological responsibility’, is that trying to make sure we never fall into error gets in the way of a tremendous amount of learning, discovery, and even of finding truth. Many of the most urgent and momentous questions we face in life - whether and who to marry, what career to pursue - cannot be decided one way or the other, so we frequently find ourselves in a position of having to take leaps of faith, or to put it more ecumenically, to form beliefs and make choices on insufficient grounds. To do that, we’ve got to let go of the fear of error, lest we remain paralysed by it.

The fear of error, in James’ interpretation, is a kind of phobia. It might be understood as a sort of psychosocial autoimmune disorder, and like any autoimmune disorders, it’s a dysfunction in our self-defenses that not only directly harms us, but makes it hard for us to protect ourselves when we have to. Fear of error produces a kind of autonomic stupidity that destroys the body and mind’s ability to distinguish between what’s harmless and real threats.

The fear of being a dupe makes us stupid, because it gets in the way of our sensitivity to differences between more and less dangerous errors. Not all errors are equally dangerous; an unjustified belief in the stability of nuclear détente is more dangerous than an unjustified belief in the benefit of community, but if we’re overly concerned with avoiding any error at all, it makes it a lot harder to appreciate the difference.

The detachment of the slacker tone is a similar kind of disordered autoimmune response, motivated by an even more fundamental paranoia than James’ ‘fear of being a dupe’ - an abject terror of vulnerability. For the paranoid, the problem with being a dupe isn’t really the error, it’s that one has failed to defend oneself, allowed oneself to be taken advantage of, made oneself vulnerable. Besides being a dupe, there are many other ways of being vulnerable, and we have learned to avoid them all.

The terror of vulnerability, like the fear of being a dupe, is paranoid; it’s got nothing whatever to do with any particular threat. It mistakes defensiveness itself for the point, forgetting that defense should be defense of or against something. As Robert Frost writes:

“Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,”

If we’ve always got our defenses up, there’s no way for us to peek over the parapets to tell if there’s actually something out there to defend against.

It’s this terror of vulnerability that lay beneath the Simpsons’ snark, and 90s slacker culture in general. On the face of it, this kind of detachment might look cool, but when we look under the hood we can see the shaking, timid reality that it’s covering up.

What culture needs instead is the courage to be sincere, to stand up for something, to risk the vulnerability it takes to say clearly, with care and feeling: “this is what I believe in.”

Dr. Noah Gabriel Martin lectures in philosophy at the University of Winchester and runs the College of Modern Anxiety, a social enterprise that promotes lifelong learning for liberation. He recently began to study dance, which has taught him a lot about being an absolute beginner.