Architecture of the Cosmos

Trisha Singh, December 23, 2025

A Hindu temple does not serve just as a place of worship but as a three-dimensional map of the universe, rendered in stone. Every line, proportion, and orientation of the building is shaped by sacred geometry, a symbolic language that expresses not just both how the cosmos is ordered and how human beings may move within it. Rooted in ancient Indian philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and ritual practice, Hindu temple architecture transforms space itself into a spiritual path. To understand a Hindu temple is to see how form can guide the devotee from the outer plane toward inner realization.

At the core of this tradition lies the Hindu understanding that the universe is not random or inert, but an ordered, intelligible, and alive entity, replete with consciousness. This order is known as ṛta, the cosmic principle that governs both natural law and moral harmony. Sacred geometry is a visible expression of ṛta, translating metaphysical truth into spatial form, and architecture actively participates in the rituals it hosts.

Central to Hindu philosophy, particularly in the Vedic and Upanishadic traditions, is the idea that the universe (brahmāṇḍa) mirrors the human being (piṇḍāṇḍa). The macrocosm and the microcosm reflect one another, like the old adage of ‘as above, so below’. Sacred geometry serves as the bridge between these two scales of existence. As one enters a temple, they symbolically enter the cosmos, and as they walk through that cosmic journey, move inward toward the Self (ātman), which Hindu philosophy identifies with ultimate reality (Brahman). The temple becomes both a map of the universe and a guide for inner transformation.

The formal principles governing this sacred space are articulated in Vāstu Śāstra, the ancient Indian science of architecture. Vāstu Śāstra integrates geometry, astronomy, directional alignment, and metaphysics, treating space as a living field of energies rather than an empty container. Land itself possesses consciousness, embodied in the figure of the Vāstu Puruṣa, a cosmic being who lies within the square grid of the temple plan. Each part of his body corresponds to specific directions, deities, and natural forces. Constructing a temple is therefore an act of biological creation —aligning human intention with cosmic order.

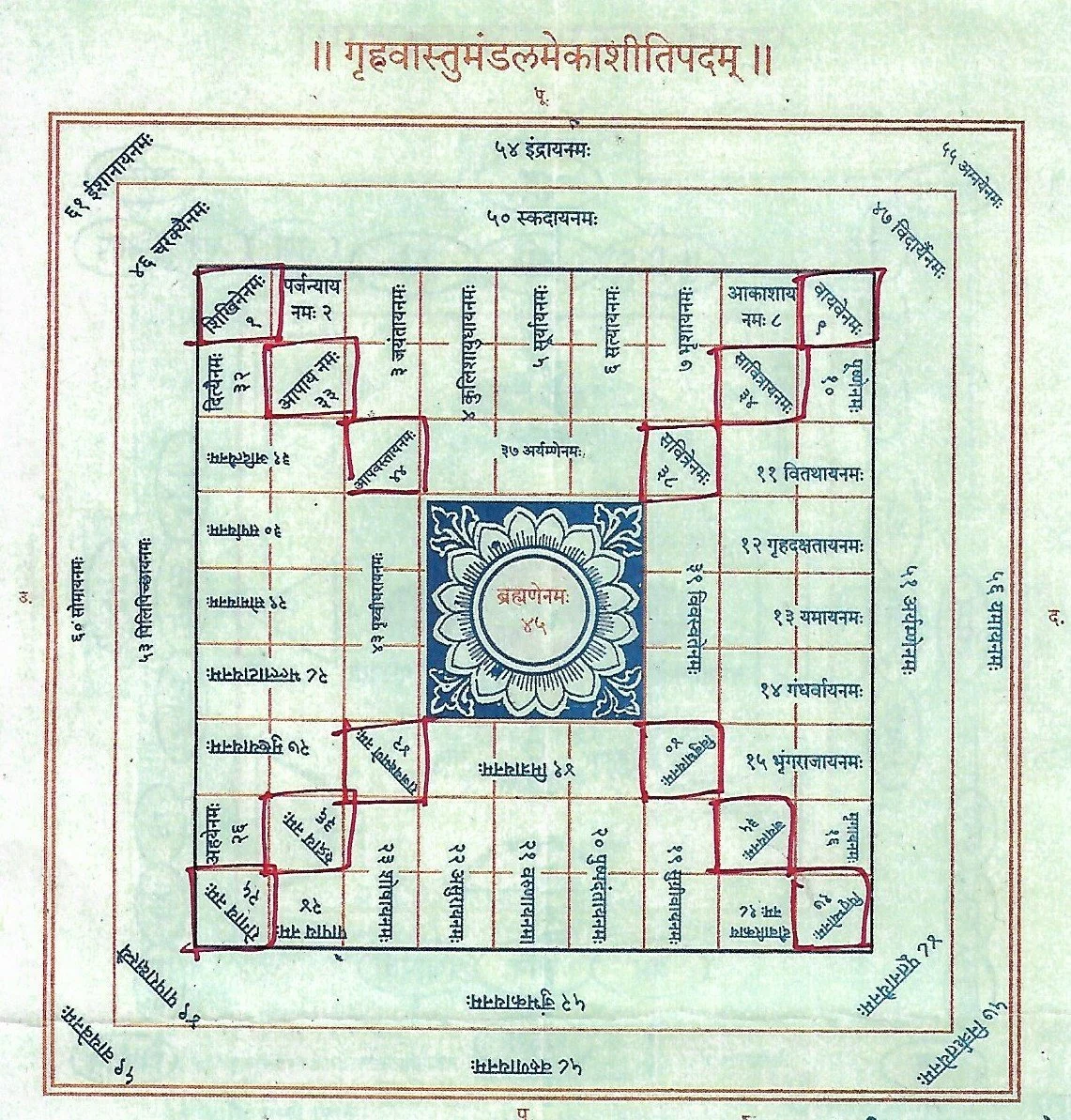

This alignment is most clearly expressed through the Vāstu Puruṣa Maṇḍala, a geometric blueprint that underlyes Hindu temple design. The mandala is both a cosmological diagram and a map of consciousness, taking the form of a geometric grid divided into sixty-four or eighty-one smaller squares, organised around a center. The central square, the Brahma Pada, represents the source of creation: pure, undifferentiated consciousness. The temple’s innermost sanctum, the garbhagṛha, is placed precisely here.

Surrounding this center, the remaining squares are assigned to various deities and cosmic forces, arranged so that energy symbolically flows inward. As we move through the structure, this can be felt tangibly and observed. Complexity of design and adornment gradually gives way to simplicity and a sense of unity. The devotee is a necessary participant in the architecture, moving towards the divine and returning to the source of all.

The geometric language of the temple is built upon two fundamental forms: the square and the circle. The square represents stability, order, and the material world, its corners corresponding to the cardinal directions and the grounded nature of human experience. As such, the square dominates the temple’s plan.

The circle, by contrast, symbolizes infinity, wholeness, and the cosmic order. It represents time, cycles, and the divine. Although temples are rarely circular in structure, their conceptual design often begins with a circle that is “squared.” The boundless reality of Brahman can take form within the finite world without being diminished.

“Unity within diversity, order within complexity, and the presence of the infinite within the finite.”

The system of measurement contributes further to this symbolic system. Hindu temple architecture employs precise units such as the aṅgula and the tāla, as dimensions follow harmonious ratios rather than arbitrary scale. These proportions resonate with cosmic order, much like musical intervals produce harmony through mathematical relationships. Space, like sound, becomes a medium through which balance and coherence are experienced.

We see this attention to proportion most clearly in the temple’s vertical dimension. The rising tower above the sanctum is designed to appear as an organic ascent and evoke the soul’s movement from the earthly realm toward higher planes of existence.

At the base of this ascent lies the garbhagṛha, the inner sanctum and “womb chamber” of the temple. Small, dark, and deliberately austere, it is a perfect square or cube, symbolizing completeness and stability. The absence of natural light and lack of ornamentation draws attention inward, towards our consciousness. As we approach the sanctum, we leave behind the sensory richness of the outer halls and enter a space of stillness and potential, with the architecture mirroring the meditative journey.

Vertical symbolism of the temple extends beyond the tower. Hindu temples are often conceived as representations of Mount Meru, the mythological axis of the universe. The temple’s central vertical line, sometimes called the brahma sūtra, aligns earth and sky, creating a conduit for cosmic energy. At the summit, the kalaśa finial signifies abundance, immortality, and the union of the earthly and the divine.

Most Hindu temples face east, greeting the rising sun as a symbol of knowledge, life, and awakening. In many temples, architectural alignment allows sunlight to illuminate the deity at specific times of the year, linking ritual practice to astronomical cycles. The temple, then, functions not only as a sacred enclosure, but as a calendar and observatory that synchronizes human worship with celestial movement.

Ultimately, the purpose of Hindu temple geometry, as with sacred geometry across cultures, is not about mathematical precision for its own sake. Instead, it functions as a symbolic language, communicating philosophical truths that words alone cannot convey: unity within diversity, order within complexity, and the presence of the infinite within the finite. The temple becomes a mirror and a participant of the universe

Hindu temple’s architecture reveal a worldview in which art, science, and spirituality are inseparable. These structures are designed not only to house deities or inspire awe, but to guide consciousness toward harmony with cosmic order. To walk through a Hindu temple is to traverse a cosmic diagram, moving from the outer world of form and multiplicity toward the silent center of being. The building becomes our teacher.

Trisha Singh is an architect and writer.