Happiness, the Nine of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 16, 2025

The Nine of Cups holds the sweetest water in the suit. As a nine, it is given to Yesod, the Unconscious, so this is the Lethean water of forgetfulness, the drink that puts you in a stupor…

Name: Happiness, the Nine of Cups

Number: 9

Astrology: Jupiter in Pisces

Qabalah: Yesod of He

Chris Gabriel August 16, 2025

The Nine of Cups holds the sweetest water in the suit. As a nine, it is given to Yesod, the Unconscious, so this is the Lethean water of forgetfulness, the drink that puts you in a stupor.

In Rider, a large man sits smugly in front of a table, upon which rests his horde of 9 cups. His arms are crossed and his face holds a haughty smile. He wears a white robe and a red turban. The table is draped with a watery table cloth.

In Thoth, we have Happiness; three rows of three pink cups flow into one another and golden lotuses move the water about the card through their orange stems. The card is given to Jupiter in Pisces, the domicile of Jupiter. As such, the Happiness of this card relates to religious ecstasy, fantasy, and metaphysics.

In Marseille, we have another matrix of cups, three by three, around which vegetation grows. At the bottom row of cups, the plants are wilting, atop they are growing strong. Qabalistically, the card is the ‘Foundation of the Queen’.

Happiness is a very pleasantly named card, and indeed the zodiacal placement which is attributed to it is one of the best. This is a restorative step in the suit of Cups where water returns to its essential nature after a difficult detour.

As Jupiter in Pisces, it brings to mind the dreams and promises offered by religion in its most base form. The promise of eternal life, paradise, and reunion with loved ones. Phrases like “pie in the sky” or “pipe dream” are particularly apt, and we can consider the root of the latter phrase being opium. The water in these cups is akin to Marx’s idea of religion as the ‘opium of the people.’ While the masses are tormented and oppressed, they hold onto the promises of the church to keep them going, rather than changing their material conditions. The pleasing water held in these nine cups is a spiritual opiate.

Many people drink and do drugs to attain this manner of dreamy hopefulness. In this state one can escape the misery and drudgery of reality, but it is ultimately temporary. The Happiness of this card is ephemeral and finite, and any attempts to make it prolong it lead to the rotting roots shown in Marseille.

The perfect image of this is the Lotus Eaters of The Odyssey, a people entirely dependent on their drugs and indifferent to the world. Many belief systems function this way as well; as numbing anesthetics for the body. The afterlife of the Greeks required the magical Lethean waters of forgetfulness to reach the end. An eternity being dumb and numb.

When we pull this card, we can expect a pleasant time, good dreams, and shared comfort. We may have a very strong imagination at this time or have sprawling dreams. Even in a reverie, we must ask ourselves: who is the dreamer? Are we in a dream of our own, or has someone trapped us in theirs?

The Soul Star Activation Protocol

Molly Hankins August 14, 2025

The Soul Star Activation Protocol was nearly lost to the world of the 21st century. A metaphysical technology passed down from Tibetan Master Djwhal Khul to Theosophical Society founder Helena Blavatsky to esoteric writer Alice A. Bailey, it was preserved in The Rainbow Bridge published in 1975…

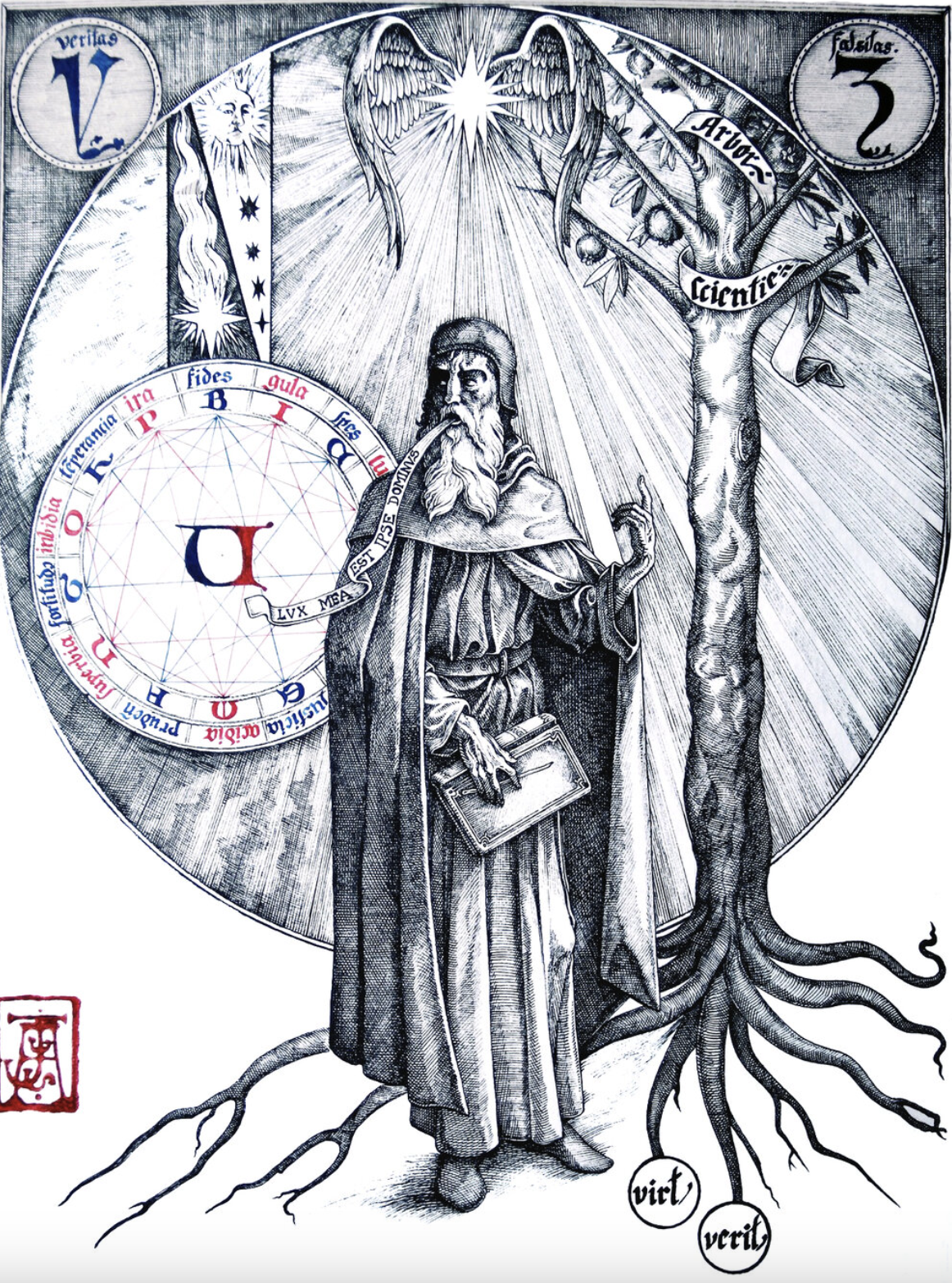

De Occulta Philosophia, Heinrich Agrippa.1533.

Molly Hankins August 14, 2025

The Soul Star Activation Protocol was nearly lost to the world of the 21st century. A metaphysical technology passed down from Tibetan Master Djwhal Khul to Theosophical Society founder Helena Blavatsky to esoteric writer Alice A. Bailey, it was preserved in The Rainbow Bridge published in 1975. It explains in elegantly simple detail how to build connection with our higher self beyond the world of form, expanding our consciousness, creativity, and magical capacity in the process. Inspired by The Kybalion, a book of Hermetic principles authored by three anonymous initiates, The Rainbow Bridge was anonymously published by two dedicated students of Theosophy and the transmission of this sacred knowledge continues.

The Rainbow Bridge describes an energetic thread “or vibration between states of consciousness” connecting our Earthly consciousness in third density to the totality of our soul’s consciousness beyond form. This thread is like a low-bandwidth data stream between worlds, that can be expanded by consciously working with this connection. The more data moving through the connection, the higher our state of consciousness and the more broad our capacity to respond to stimulus is. As it expands through effort, it hits critical mass,the bandwidth is suddenly expanded exponentially, and the connection is no longer a low bandwidth thread, but what the authors refer to as a “rainbow bridge”. When this happens, our soul star is activated.

“As consciousness moves from point to point or level to level from Earth upward, man’s nature changes even though his form appears to be the same; in reality it becomes more refined in the substance and energy of which it is composed. There comes a time when centers above the physical body are touched, and man finds himself in a state of being which, although new, seems to be the very essence of his being and somehow, strangely and wonderfully the essence of all being,” the introduction states. “At first there appears to be no difference in his outer vehicles or life, but, in time, he becomes something different, and he does not need to die to experience Heaven. Such experience is one of the goals of all occult teachings and practices.” When the centers above the physical body become activated, so does our soul star.

Master Djwhal Khul’s protocol has four qualifying requirements to build this connection and activate their soul star. Khul believes undertaking this work requires integration of the following principle beliefs into our consciousness before beginning the protocol:

The is one all inclusive, original source of consciousness also known as God, Intelligence, the Absolute, etc.

There is a law of rebirth, reincarnation or cyclic return.

Karma is a law of cause and effect we all live within.

There is a law of unification on the path of return from form back to the original source of consciousness, all souls are part of the one soul.

Once the above tenets are accepted and integrated, students may begin the Soul Star Activation Protocol. The soul star, the book tells us, is a bright, white indicator light that sits about 6 inches above the top of our heads and can be seen by energetically sensitive people when the data stream between our human and higher selves sufficiently expands. Activating it requires us to consciously build the connection within our physical and energetic bodies, referred to as the “central channel.” This channel runs through our heads and into the Earth. Those who are called to this work have at least a minimally activated soul star, and consciously engaging with it will begin the activation.

“Activating our soul star burns off so much psychic debris, as well as that accrued through traumas and the stress of daily life.”

To begin the Protocol, we must speak or sing the following soul mantram:

I am the soul, I am the light divine, I am love, I am will, I am fixed design.

The final phrase refers to the idea that our soul makes a plan for the lessons they need to learn in every incarnation, in order to reap the most benefit of being in form. The soul and personal self’s objectives are not the same, but part of this work is to begin identifying with the soul as much as possible. After vocalizing the soul mantra, the protocol begins by fixing our attention on our soul star and using triangulation to consciously move the star at a 45 degree angle in front of our forehead. Next we inhale to consciously move our soul star to our third eye, then exhale to move it along the pathway of the central channel and back to its resting place six inches above our heads. The conscious movement of our soul star is in the shape of a triangle.

“By this mental direction of energy, a student is enabled to clear away a channel for the continuous flow of spiritual energies through the lower vehicles or bodies,” the book says. “This is a slow and gradual process because it must be done under control and without haste or carelessness.” Students are advised to begin working just with the single triangulation through the third eye, practising l daily for at least two weeks before adding the second triangle, which moves the soul star just as before at a 45 degree angle in front of the throat then brings it back into the body and up the central channel. With each new triangle, spend two weeks practicing before moving on and introducing more. It takes four months to develop a central channel that fully utilizes the protocol, and the final two triangles through our feet into the Earth must be completed from a standing position.

Activating our soul star burns off so much psychic debris, as well as that accrued through traumas and the stress of daily life. After each session working the protocol we must clean our energy bodies using what’s called the ‘spiritual whirlwind’. You can imagine and concentrate on a tornado-like energy coming down above our heads and into the Earth, moving clockwise to remove all psychic debris. This part of the exercise should be performed for at least three minutes and be included as part of the protocol for those first four months. After that, the spiritual whirlwind may be used as needed, but most of the debris can be burned off in those early months through diligent practice. Recognizing when the whirlwind is no longer necessary is part of becoming more energetically sensitive from this training, so only individual intuition can inform the right time to remove it from the protocol.

Working with the central channel via triangulation, students typically find they don’t want to stop. Building the connection feels so good and is such a supercharge to our personal magic, most of those working with the Soul Star Activation Protocol find themselves integrating it into daily meditations and rituals. Not only does this work benefit our individual, Earthly lives, it also accelerates the evolution of planetary consciousness. “Effects increase with time, application and progressive purification,” the book promises, and as alignment with our soul increases, so does our personal and collective enjoyment of the human experience.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

Against Fluency

Arcadia Molinas August 12, 2025

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you…

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Arcadia Molinas August 12, 2025

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you. A book can instantly transport you to cities, countries and worlds you’ve never set foot on. A book can take you to new climates, suggest the taste of new foods, introduce you to cultures and confront you with entirely different ways of being. It is a way to move and to travel without ever leaving the comfort of your chair.

Books in translation offer these readerly delights perhaps more readily than their native counterparts. Despite this, the work of translation is vastly overlooked and broadly underappreciated. In book reviews, the critique of the translation itself rarely takes up more than a throwaway line which comments on either the ‘sharpness’ or ‘clumsiness’ of the work. It is uncommon, too, to see the translator’s name on the cover of a book. A good translation, it seems, is meant to feel invisible. But is travelling meant to feel invisible – identical, seamless, homogenous? Or is travelling meant to provoke, cause discomfort, scream its presence in your face? The latter seems to me to be the more somatic, erotic, up in your body experience and thus, more conducive to the moral component of the vice of reading.

French translator Norman Shapiro describes the work of translation as “the attempt to produce a text so transparent that it does not seem to be translated. A good translation is like a pane of glass. You only notice that it’s there when there are little imperfections— scratches, bubbles. Ideally, there shouldn’t be any. It should never call attention to itself.” This view is shared by many: a good translation should show no evidence of the translator, and by consequence, no evidence that there was once another language involved in the first place at all. Fluency, naturalness, is what matters – any presence of the other must be smoothed out. For philosopher Friedreich Schlerimacher however, the matter is something else entirely. For him, “there are only two [methods of translation]. Either the translator leaves the author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him.” He goes on to argue for the virtues of the former, for a translation that is visible, that moves the reader’s body and is seen and felt. It’s a matter of ethics for the philosopher – why and how do we translate? These are not minor questions when considering the stakes of erasing the presence of the other. The repercussions of such actions could reflect and accentuate larger cultural attitudes to difference and diversity as a whole.

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Lawrence Venuti coins Schlerimacher’s two movements, from reader to author and author to reader, as ‘foreignization’ and ‘domestication’ in his book The Translator’s Invisibility. Foreignization is “leaving the author in peace and moving the reader towards him”, which means reflecting the cultural idiosyncrasies of the original language onto the translated/target one. It means making the translation visible. Domestication is the opposite, it irons out any awkwardness and imperfections caused by linguistic and cultural difference, “leaving the reader in peace and moving the author towards him”. It means making the translation invisible, and is the way translation is so often thought about today. Venuti says the aim of this type of translation is to “bring back a cultural other as the same, the recognizable, even the familiar; and this aim always risks a wholesale domestication of the foreign text, often in highly self- conscious projects, where translation serves an appropriation of foreign cultures for domestic agendas, cultural, economic, political.”

The direction of movement in these two strategies makes all the difference. Foreignization makes you move and travel towards the author, while domestication leaves you alone and doesn’t disturb you. There is, Venuti says, a cost of being undisturbed. He writes of the “partly inevitable” violence of translation when thinking about the process of ironing out differences. When foreign cultures are understood through the lens of a language inscribed with its own codes, and which consequently carry their own embedded ways of regarding other cultures, there is a risk of homogenisation of diversity. “Foreignizing translation in English”, Venuti argues, “can be a form of resistance against ethnocentrism and racism, cultural narcissism and imperialism, in the interests of democratic geopolitical relations.” The potential for this type of reading and of translating is by no means insignificant.

To embrace discomfort then, an uncomfortable practice of reading, is a moral endeavour. To read foreignizing works of translation is to expand one’s subjectivity and suspend one’s unified, blinkered understanding of culture and linguistics. Reading itself is a somatic practice, but to read a work in translation that purposefully alienates, is to travel even further, it’s to go abroad and stroll through foreign lands, feel the climate, chew the food. It’s well acknowledged that the higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view. And to get the bigger picture is as possible to do as sitting on your favourite chair, opening a book and welcoming alienation.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer, editor, and translator from Madrid. She currently works as the online editor of Worms Magazine and has published a Spanish translation of Virginia Woolf’s diaries with Funambulista.

Page and Princess of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 9, 2025

The Page of disks is the lowest court card, the earthiest part of the earth. It is the seed, small in size but immense in potential…

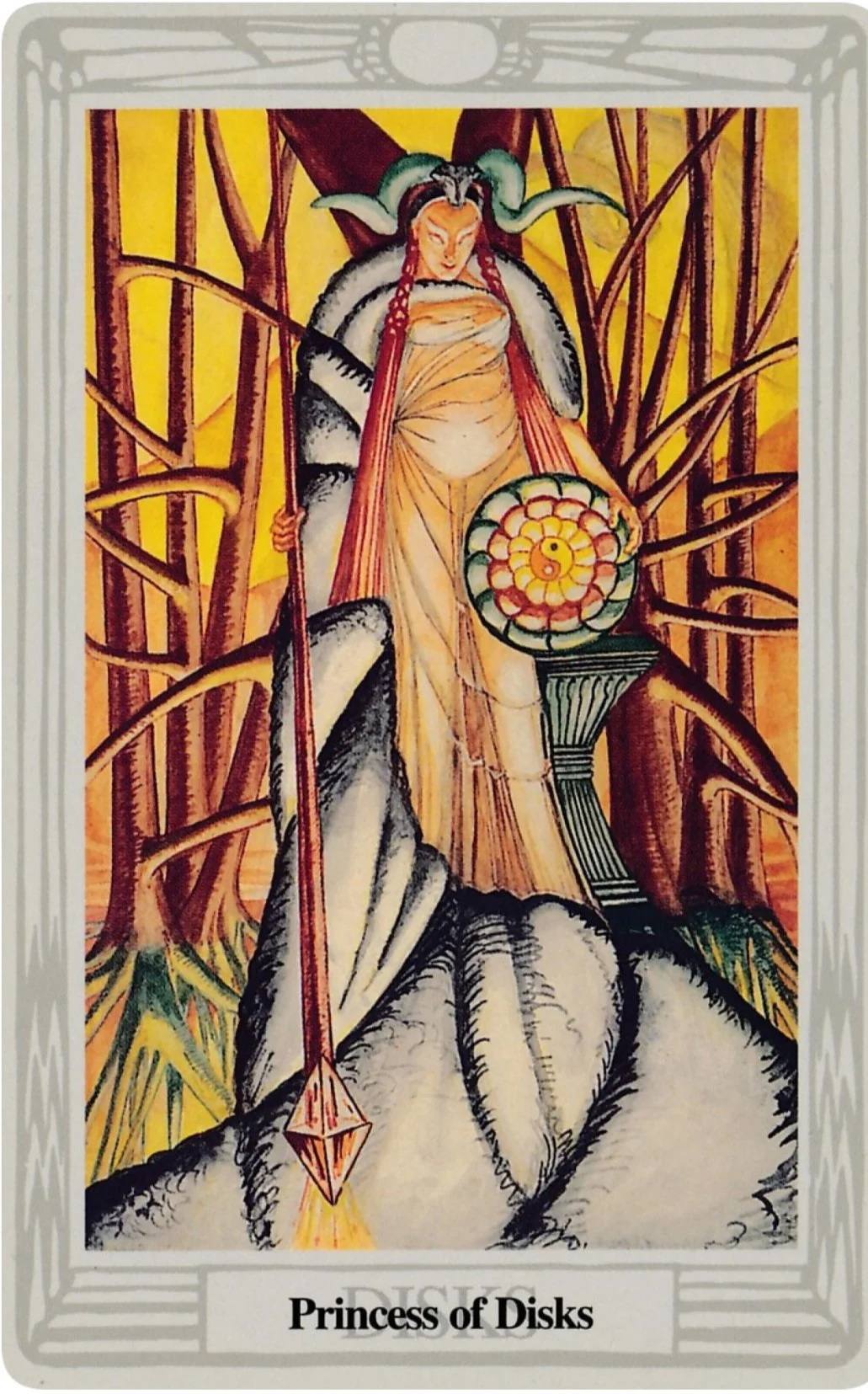

Name: Page/Princess of Disks

Number: 4

Astrology: Earth of Earth

Qabalah: He of He

Chris Gabriel August 9, 2025

The Page of Disks is the lowest court card, the earthiest part of the earth. It is the seed, small in size but immense in potential. In each depiction, the young figure holds a disk which they look upon carefully.

In Rider, the Page is a young man wearing a simple green tunic with tan undergarments. He dons a red turban, gently upholds his disk with both hands, and looks upon it happily. Little wildflowers grow at his feet.

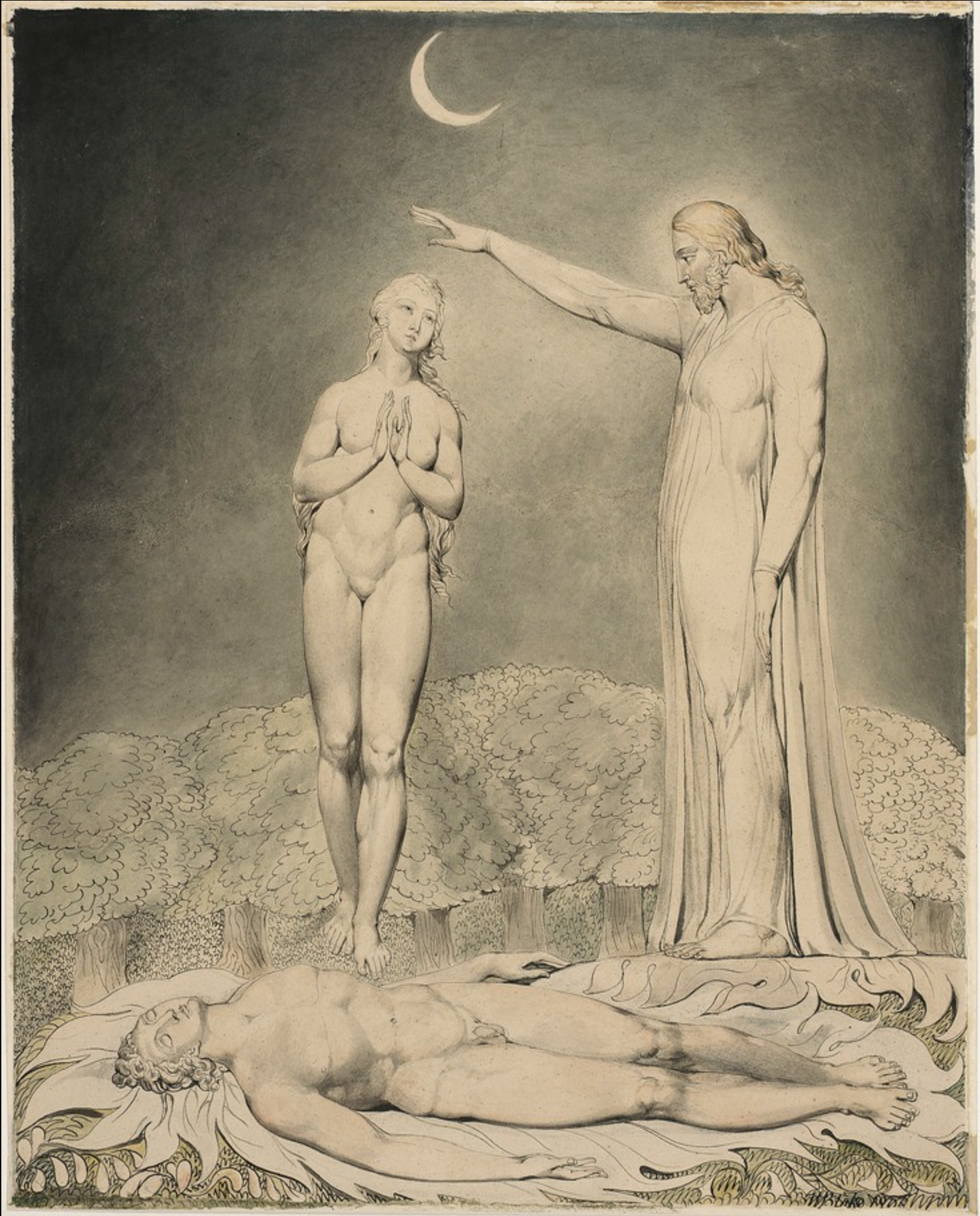

In Thoth, the Princess wears a diaphanous gown and a great fur. She is crowned by a goat’s skull. Her disk is a flower whose center is a Tajitu, a Yin and Yang symbol. She holds a scepter, with its crystal base towards the ground. She smiles, looking down at her pregnancy and blossoming disk.

In Marseille, the Valet is a stern young man. He grips his belt with one hand, and carefully inspects the disk he holds in the other. His feet are pointed in each direction upon barren soil. A few scrubs grow in the waste, but his duty is to bring the earth to life.

The role of this card is to restore life to the barren Earth. Each year, we see plant life die in the winter and begin to blossom again in the spring: this is the place of the Page, themselves the fertile earth.

This fertility extends beyond the flora and to the animal in Thoth. The Princess of Disks is in fact the only card in the deck which features a pregnant woman. In my experience, this card has directly indicated a real pregnancy multiple times. Beyond the physical, this is the natural mind of man, untouched and fertile, ready for inspiration.

It can help to understand this card alongside a concept from the Tao Te Ching: Pu 樸

The characters in this name are Tree and Forest, and is commonly known as “Uncarved Wood”; the wood still in the forest. This is akin to a slab of marble still held in a quarry, not yet sculpted. In the west we have similar concepts, like “Carte Blanche”, a blank paper with which we can dictate freely.

The Page is a person given a blank check, a blank piece of paper, a block of wood, or a slab of marble. It is what they do with this tabula rasa that matters. In this way, the Princess as a future mother and her unborn child are perfect symbols of infinite potential.

When pulling this card, we are to be given something that we must work upon. One may have to build from the ground up or start a grassroots project. We may become increasingly receptive to inspiration, or, indeed, become literally pregnant.

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas

Ursula Le Guin August 7, 2025

With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city Omelas, bright-towered by the sea…

Un Autre Monde, J. J. Grandville. 1844.

A masterpiece of philosophical fiction, Le Guin’s story has reverberated across generations since it was first published in 1973. At once readable as an allegory for Christ’s sacrifice and as a questioning of the very premise of utilitarianism, ‘Omelas’ is above all else a vivid parable of the modern age. In a world where happiness relies on the abject misery of a single person, we can see clearly the inequality and be disgusted by the injustice - Le Guin creates this world and asks us to look deeper into our own, where the same moral issues are happening everyday yet so few of us choose to walk away from our ‘Omelas’.

Ursula Le Guin August 7, 2025

With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city Omelas, bright-towered by the sea. The rigging of the boats in harbor sparkled with flags. In the streets between houses with red roofs and painted walls, between old moss-grown gardens and under avenues of trees, past great parks and public buildings, processions moved. Some were decorous: old people in long stiff robes of mauve and grey, grave master workmen, quiet, merry women carrying their babies and chatting as they walked. In other streets the music beat faster, a shimmering of gong and tambourine, and the people went dancing, the procession was a dance. Children dodged in and out, their high calls rising like the swallows’ crossing flights, over the music and the singing. All the processions wound towards the north side of the city, where on the great water-meadow called the Green’ Fields boys and girls, naked in the bright air, with mud-stained feet and ankles and long, lithe arms, exercised their restive horses before the race. The horses wore no gear at all but a halter without bit. Their manes were braided with streamers of silver, gold, and green. They flared their nostrils and pranced and boasted to one another; they were vastly excited, the horse being the only animal who has adopted our ceremonies as his own. Far off to the north and west the mountains stood up half encircling Omelas on her bay. The air of morning was so clear that the snow still crowning the Eighteen Peaks burned with white-gold fire across the miles of sunlit air, under the dark blue of the sky. There was just enough wind to make the banners that marked the racecourse snap and flutter now and then. In the silence of the broad green meadows one could hear the music winding through the city streets, farther and nearer and ever approaching, a cheerful faint sweetness of the air that from time to time trembled and gathered together and broke out into the great joyous clanging of the bells.

Joyous! How is one to tell about joy? How describe the citizens of Omelas?

They were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy. But we do not say the words of cheer much any more. All smiles have become archaic. Given a description such as this one tends to make certain assumptions. Given a description such as this one tends to look next for the King, mounted on a splendid stallion and surrounded by his noble knights, or perhaps in a golden litter borne by great-muscled slaves. But there was no king. They did not use swords, or keep slaves. They were not barbarians. I do not know the rules and laws of their society, but I suspect that they were singularly few. As they did without monarchy and slavery, so they also got on without the stock exchange, the advertisement, the secret police, and the bomb. Yet I repeat that these were not simple folk, not dulcet shepherds, noble savages, bland utopians. They were not less complex than us. The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain. If you can’t lick ’em, join ’em. If it hurts, repeat it. But to praise despair is to condemn delight, to embrace violence is to lose hold of everything else. We have almost lost hold; we can no longer describe a happy man, nor make any celebration of joy. How can I tell you about the people of Omelas? They were not naive and happy children – though their children were, in fact, happy. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched. O miracle! but I wish I could describe it better. I wish I could convince you. Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale, long ago and far away, once upon a time. Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids, assuming it will rise to the occasion, for certainly I cannot suit you all. For instance, how about technology? I think that there would be no cars or helicopters in and above the streets; this follows from the fact that the people of Omelas are happy people. Happiness is based on a just discrimination of what is necessary, what is neither necessary nor destructive, and what is destructive. In the middle category, however – that of the unnecessary but undestructive, that of comfort, luxury, exuberance, etc. – they could perfectly well have central heating, subway trains,. washing machines, and all kinds of marvelous devices not yet invented here, floating light-sources, fuelless power, a cure for the common cold. Or they could have none of that: it doesn’t matter. As you like it. I incline to think that people from towns up and down the coast have been coming in to Omelas during the last days before the Festival on very fast little trains and double-decked trams, and that the train station of Omelas is actually the handsomest building in town, though plainer than the magnificent Farmers’ Market. But even granted trains, I fear that Omelas so far strikes some of you as goody-goody. Smiles, bells, parades, horses, bleh. If so, please add an orgy. If an orgy would help, don’t hesitate. Let us not, however, have temples from which issue beautiful nude priests and priestesses already half in ecstasy and ready to copulate with any man or woman, lover or stranger who desires union with the deep godhead of the blood, although that was my first idea. But really it would be better not to have any temples in Omelas – at least, not manned temples. Religion yes, clergy no. Surely the beautiful nudes can just wander about, offering themselves like divine souffles to the hunger of the needy and the rapture of the flesh. Let them join the processions. Let tambourines be struck above the copulations, and the glory of desire be proclaimed upon the gongs, and (a not unimportant point) let the offspring of these delightful rituals be beloved and looked after by all. One thing I know there is none of in Omelas is guilt. But what else should there be? I thought at first there were no drugs, but that is puritanical. For those who like it, the faint insistent sweetness of drooz may perfume the ways of the city, drooz which first brings a great lightness and brilliance to the mind and limbs, and then after some hours a dreamy languor, and wonderful visions at last of the very arcana and inmost secrets of the Universe, as well as exciting the pleasure of sex beyond all belief; and it is not habit-forming. For more modest tastes I think there ought to be beer. What else, what else belongs in the joyous city? The sense of victory, surely, the celebration of courage. But as we did without clergy, let us do without soldiers. The joy built upon successful slaughter is not the right kind of joy; it will not do; it is fearful and it is trivial. A boundless and generous contentment, a magnanimous triumph felt not against some outer enemy but in communion with the finest and fairest in the souls of all men everywhere and the splendor of the world’s summer; this is what swells the hearts of the people of Omelas, and the victory they celebrate is that of life. I really don’t think many of them need to take drooz.

“They feel disgust, which they had thought themselves superior to. They feel anger, outrage, impotence, despite all the explanations. They would like to do something for the child. But there is nothing they can do.”

Most of the processions have reached the Green Fields by now. A marvelous smell of cooking goes forth from the red and blue tents of the provisioners. The faces of small children are amiably sticky; in the benign grey beard of a man a couple of crumbs of rich pastry are entangled. The youths and girls have mounted their horses and are beginning to group around the starting line of the course. An old woman, small, fat, and laughing, is passing out flowers from a basket, and tall young men, wear her flowers in their shining hair. A child of nine or ten sits at the edge of the crowd, alone, playing on a wooden flute. People pause to listen, and they smile, but they do not speak to him, for he never ceases playing and never sees them, his dark eyes wholly rapt in the sweet, thin magic of the tune.

He finishes, and slowly lowers his hands holding the wooden flute.

As if that little private silence were the signal, all at once a trumpet sounds from the pavilion near the starting line: imperious, melancholy, piercing. The horses rear on their slender legs, and some of them neigh in answer. Sober-faced, the young riders stroke the horses’ necks and soothe them, whispering, ”Quiet, quiet, there my beauty, my hope…” They begin to form in rank along the starting line. The crowds along the racecourse are like a field of grass and flowers in the wind. The Festival of Summer has begun.

Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing.

In a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, or perhaps in the cellar of one of its spacious private homes, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window. A little light seeps in dustily between cracks in the boards, secondhand from a cobwebbed window somewhere across the cellar. In one corner of the little room a couple of mops, with stiff, clotted, foul-smelling heads, stand near a rusty bucket. The floor is dirt, a little damp to the touch, as cellar dirt usually is. The room is about three paces long and two wide: a mere broom closet or disused tool room. In the room a child is sitting. It could be a boy or a girl.It looks about six, but actually is nearly ten. It is feeble-minded. Perhaps it was born defective or perhaps it has become imbecile through fear, malnutrition, and neglect. It picks its nose and occasionally fumbles vaguely with its toes or genitals, as it sits haunched in the corner farthest from the bucket and the two mops. It is afraid of the mops. It finds them horrible. It shuts its eyes, but it knows the mops are still standing there; and the door is locked; and nobody will come. The door is always locked; and nobody ever comes, except that sometimes-the child has no understanding of time or interval – sometimes the door rattles terribly and opens, and a person, or several people, are there. One of them may come and kick the child to make it stand up. The others never come close, but peer in at it with frightened, disgusted eyes. The food bowl and the water jug are hastily filled, the door is locked, the eyes disappear. The people at the door never say anything, but the child, who has not always lived in the tool room, and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice, sometimes speaks. ”I will be good,” it says. ”Please let me out. I will be good!” They never answer. The child used to scream for help at night, and cry a good deal, but now it only makes a kind of whining, ”eh-haa, eh-haa,” and it speaks less and less often. It is so thin there are no calves to its legs; its belly protrudes; it lives on a half-bowl of corn meal and grease a day. It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually.

They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas. Some of them have come to see it, others are content merely to know it is there. They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.

This is usually explained to children when they are between eight and twelve, whenever they seem capable of understanding; and most of those who come to see the child are young people, though often enough an adult comes, or comes back, to see the child. No matter how well the matter has been explained to them, these young spectators are always shocked and sickened at the sight. They feel disgust, which they had thought themselves superior to. They feel anger, outrage, impotence, despite all the explanations. They would like to do something for the child. But there is nothing they can do. If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms. To exchange all the goodness and grace of every life in Omelas for that single, small improvement: to throw away the happiness of thousands for the chance of the happiness of one: that would be to let guilt within the walls indeed.

The terms are strict and absolute; there may not even be a kind word spoken to the child.

Often the young people go home in tears, or in a tearless rage, when they have seen the child and faced this terrible paradox. They may brood over it for weeks or years. But as time goes on they begin to realize that even if the child could be released, it would not get much good of its freedom: a little vague pleasure of warmth and food, no doubt, but little more. It is too degraded and imbecile to know any real joy. It has been afraid too long ever to be free of fear. Its habits are too uncouth for it to respond to humane treatment. Indeed, after so long it would probably be wretched without walls about it to protect it, and darkness for its eyes, and its own excrement to sit in. Their tears at the bitter injustice dry when they begin to perceive the terrible justice of reality, and to accept it. Yet it is their tears and anger, the trying of their generosity and the acceptance of their helplessness, which are perhaps the true source of the splendor of their lives. Theirs is no vapid, irresponsible happiness. They know that they, like the child, are not free. They know compassion. It is the existence of the child, and their knowledge of its existence, that makes possible the nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music, the profundity of their science. It is because of the child that they are so gentle with children. They know that if the wretched one were not there snivelling in the dark, the other one, the flute-player, could make no joyful music as the young riders line up in their beauty for the race in the sunlight of the first morning of summer.

Now do you believe in them? Are they not more credible? But there is one more thing to tell, and this is quite incredible.

At times one of the adolescent girls or boys who go to see the child does not go home to weep or rage, does not, in fact, go home at all. Sometimes also a man or woman much older falls silent for a day or two, and then leaves home. These people go out into the street, and walk down the street alone. They keep walking, and walk straight out of the city of Omelas, through the beautiful gates. They keep walking across the farmlands of Omelas. Each one goes alone, youth or girl man or woman. Night falls; the traveler must pass down village streets, between the houses with yellow-lit windows, and on out into the darkness of the fields. Each alone, they go west or north, towards the mountains. They go on. They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.

Ursula K. Le Guin ( 1929 – 2018) was an American author, best known for her science fiction works The Hainish Cycle and The Earthsea Cycle. Over the course of her life, she wrote more than twenty novels and more than a hundred shrot stories, as well as seminal works of literary criticism.

Enfolded in Living Reality Pt. 1

Tuukka Toivonen August 5, 2024

Our modern understanding of reality is a curious thing…

Plate from Oculus Artificialis, Johann Zahn. 1685.

Tuukka Toivonen August 5, 2025

“…reality is not an animated version of our re-presentation of it, but our re-presentation a devitalised version of reality. It is the re-presentation that is a special, wholly atypical and imaginary, case of what is truly present, as the filmstrip is of life […].”

-Iain McGilchrist in The Matter with Things (2021)

Our modern understanding of reality is a curious thing. We have all been told, at one point or another, to “get real” or to “live in the real world”, lest we veer too far from the parameters of a typical, ordained life course. We are called to engage in regular “reality-checks”, in order to recognize that not all of the ideas and trajectories we choose can succeed in realistic conditions. Exhortations and assumptions of this kind are what our familiar social universe is composed of, and how it gets maintained. And then we have the physicists, from Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking to Michio Kaku and Carlo Rovelli, who approach reality and the ways it is constituted as the ultimate question for science. Their mind-bending quantum theories suggest that reality is only produced when particles that simultaneously exist in multiple locations become observed, taking specific properties and therefore becoming real. The infinite possibilities that exist as a wave function suddenly collapse into matter made of tangible particles — although even particles themselves have been shown to become fuzzy under close analysis.¹ Some physicists and philosophers even postulate that we exist inside a simulation, or that reality constantly keeps splitting into parallel worlds, creating infinite copies of us without our awareness. We are, it seems, still far from having reality all figured out.

Being perched between these two extremes — treating reality rather casually and narrowly within familiar social contexts while acknowledging the discoveries of physicists that fundamentally challenge our assumptions of what is real — makes exploring the topic of reality difficult. Theories of how reality is socially constructed, always contested and ever-changing, were useful within sociology in an earlier era, but now seem complicit in flattening our existence by reducing it — indeed confining it — to language, symbols and institutions.² The conceptual world of quantum physics, despite a considerable number of thinkers who have explored how it might intersect in ways that affect day-to-day lives, starting with Carl Jung’s ideas on synchronicity, often feels disconnected from human experience.) Perhaps, then, there is a terrain between those two poles that, regardless of our relative inattention to it, might be just the right starting point for questioning human reality in the 21st century. What is it, exactly, that we have been missing due to our polarized take on reality?

This gap is perhaps the space of a rarely-articulated living reality, a subtle experiential dimension right there before our eyes (and other sense organs), but that we normally overlook and under-value. Artists such as Yuko Kurihara, whose paintings transform the wonderfully uneven, vibrant surfaces of pumpkins, bananas and oranges into an absorbing universe of their own,³ remind us of the hidden layers of reality and the potential we have to perceive them quite readily, given time and the right quality of mind. Contrary to our belief that the words we employ correspond to an actual reality in the moment that we gesture toward it, what seems to occur instead is that the words themselves come to form their own — superficial and simplified, relationally diminished — world. Perceptual reality, meanwhile, slips away from view in all its unspoken richness, receding to the background as mere potential. We are far too quick to “collapse” the infinite possibilities, depths and textures of reality into an impoverished stand-in. This is, of course, partly unavoidable for it would surely be impossible to navigate daily life if we stopped to perceive every single thing anew each time. Yet it is troubling all the same how unaware we are of our casual reductive habits and how easily they can obscure the living nature of reality and our awareness of it, relegating us to live a substitute for a real human existence.

It seems to me that contemporary technological society has not merely inherited our perceptual poverty but appears to be hell-bent on further reducing our reality to fixed categories, prescriptions, images and algorithms. The powerful cognitive technologies we are in a rush to develop and disseminate build directly on our already-impoverished version of reality. It is logical to assume that they will only entrench this thinnest of realities, locking us more firmly within its confines, or specific regimes of power, as foreseen in Yuval Noah Harari’s⁴ ominous reading of the situation. Many of these technologies will impose progressively stricter and stricter limits on what we can experience and how, drawing our attention to those slivers of presumed reality, based on arbitrary choices, that we think can be easily measured and quantified. Health comes to be appraised and understood through wearables and apps, while the ever-evolving creative process becomes reduced to mere “content”. Unique human voices — our most intimate of expressive instruments — become synthesized into digital production tools deprived of subtlety and immeasurably precious and intrinsically interwoven ecosystems come to be regarded as worthless if they fail to bend to the needs of scalable business and investment. Whatever still survives within this arid, flattened universe of controlled reality could be easily starved to death as the forces of reductionism accelerate at the expense of the kind of expanded, life-giving, delicate awareness I described above.

We have, thankfully, not yet arrived at a full culmination of these developments. There is still time to counter the forces that overwhelm us with artificial stimuli and that try to lock us into realities that are narrower and narrower in character. It is still possible, I like to believe, to cultivate and maintain a kind of supple, open awareness and quality of mind that allows us to remain in touch with living, pulsating reality. The second part of this essay will delve further into this profoundly important challenge, which ultimately asks us to choose between two radically different understandings of reality: one as a fragmented patchwork of representations, the other as complex, continuous, alive and whole.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Cossins, D. (ed.) (2025) How to think about reality. New Scientist, London.

² Berger, P.L., Luckmann, T., 1966. The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Garden City, New York, Anchor Books.

³ Some of Kurihara’s works can be viewed on her Instagram account: https://www.instagram.com/kuri_nihonga/

⁴ Harari, Y.N., 2024. Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI. Fern Press, London.

Justice/Adjustment (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 2, 2025

Justice holds a sword and scale. Traditionally, the sword is in her right hand, while the left holds the balance. She is seated and crowned. This is the Roman goddess Justitia and the Egyptian goddess Maat…

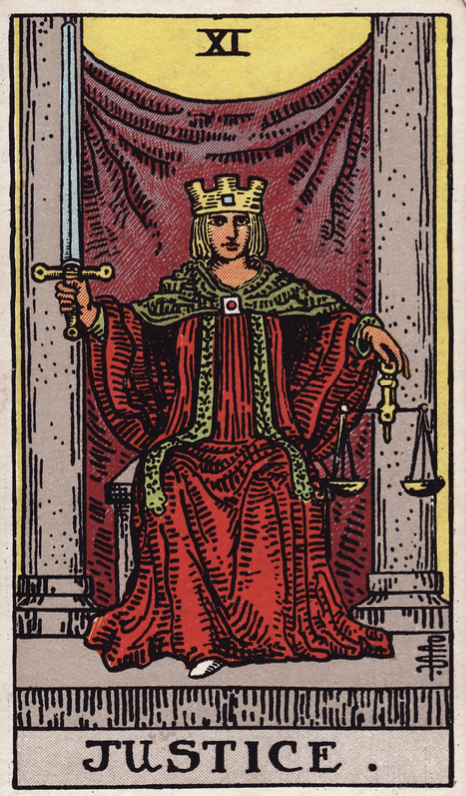

Name: Justice or Adjustment

Number: XI or VIII

Astrology: Libra

Qabalah: Lamed, the Crook or Staff

Chris Gabriel August 2, 2025

Justice holds a sword and scale. Traditionally, the sword is in her right hand, while the left holds the balance. She is seated and crowned. This is the Roman goddess Justitia and the Egyptian goddess Maat.

In Rider, Justice is young, blonde, and androgynous. Their robes are red with golden trim, and

they wear a simple gold crown. They sit on a stone chair between two columns. Their right hand

holds the sword aloft, level to their neck, while the scales are hung down. They look ahead

stoically.

In Thoth, we have a very different image. Here Justice is “Adjustment”

, and the figure is the

Egyptian goddess Maat - consort to Thoth, divinity of balance. She stands, holding her sword to

the ground with both hands. She herself forms the scale, which holds the symbols for Air and

Libra. Her body is green with streaks of blue.

In Marseille, the Queen is blonde, she looks upon her sealed cup and holds a wavy dagger, ready to defend what is hers.

In each depiction we are given a very different form of Justice: the worldly institutions and human judgments of Marseille, the praeter-human divine Justice of Rider, and the embodied balance of Maat in Thoth.

Justice, as a concept, has not been with man from the beginning. It was invented by Plato and Aristotle in the first century and, as Nietzsche points out, has little basis in nature. The idea of equality is political and utopian; it is an ideal rather than an achievable state. Marseille shows this clearly. Rider believes in a divine law, and a fair administration of it. With Maat, we get a very different view.

The Egyptians did not strive for justice, but for maintaining balance and equilibrium. Maat is the goddess not only over the moral affairs of mankind, but the very cosmos too. She wages an endless battle against Chaos. The ordered nature of the celestial cycles, the seasons, and the flooding of the Nile, were all thanks to her. She was depicted as an Ostrich, and her feathers were the symbol of balance. The hearts of men would be set on a scale and measured against one of her feathers in the afterlife.

Often, the legal system is disappointing and imbalanced, and few people feel that justice is consistently served. Religious thinkers generally believe that God will administer justice in the end. With Maat, and adjustment, one can embody balance, and in doing so help to bring the world into homeostasis.

The Hebrew letter Lamed, the Crook, is given to this card. The crook of a shepherd helps to direct sheep, or catch them when they stray from the path. This is an ideal image of Justice, sitting beyond punishment or morality. There is a balanced path forward which mankind must follow. To stray is to fall into chaos.

When pulling this card, we may be met with the consequences of our actions, good or bad. This can be a “reality check” if one has been feeling too high, or a boost, if one has been feeling too low. This can also be pleasant social interaction.

Inside Reality Center's Harmonic Resolution Mission

Molly Hankins July 31 2025

The paradox at the heart of Reality Center in Los Angeles, which offers a comprehensive nervous system reset via “digital psychedelics,” is that the experience allows us to drop reality entirely for a little while before optimizing performance upon return…

The Splash of a Drop, Professor A. M. Worthington.1895.

Molly Hankins July 31, 2025

The paradox at the heart of Reality Center in Los Angeles, which offers a comprehensive nervous system reset via “digital psychedelics,” is that the experience allows us to drop reality entirely for a little while before optimizing performance upon return. Both reality itself and our performance within it feel like they’ve elevated following a session, akin to playing a freshly tuned musical instrument. While the term digital psychedelics is technically correct to describe how light and sound are used to mimic an altered state, it hardly captures the full essence. Walking into their neon-lit facility inside an old brick building that once housed Santa Monica’s municipal offices in the early 20th century, it’s unclear whether you’re arriving at a law office or an underground rave.

Past the reception room, where your shoes are removed and your Reality Management Technician greets you, lies a large, dark, high-ceiling room with a massive projection screen in front of four sound-wave table beds. Inside one of the smaller rooms surrounding the main hall, filled with more sound-wave beds and post-experience integration areas, is where your voice is sampled to create custom binaural beats in real time. Reality Center’s proprietary software, InTune, does just that, as well as map your voice to generate data for 12 different emotional biomarkers represented onscreen by different colors. This is not first generation technology, it’s something neuroscientist Don Estes has been working on for over 40 years that has now been simplified and brought to life with Reality Center’s Millennial co-founders.

He describes a successful session as resulting in, “…a state of mind that occurs when the survival mechanism is turned off and the mind can experience feelings of peace and well-being, connectedness, faith, trust and communion with the higher self.” In Don’s essay, he describes the intended benefits of the digital psychedelic experience, which he calls a harmonic resolution. “All human suffering”, he writes, “stems from the difference between who a person says they are and who they really are. This difference creates a tension that functions like a black hole, drawing in resonant people, places, events, circumstances, and situations in an attempt to resolve the tension. This is the theme of the current universal age. The whole of the universe cannot be united until every individual part has integrated its own self.” Integration of self is effortless when our nervous system is entrained using vibration, and this is the basis for a theory he developed called sensory resonance. It posits that there are both resonant and dissonant effects on our autonomic nervous system created by the choices we make.

Enter the Raj brothers, Tarun and Pranab, who were already engaged with sensory resonance practices, making binaural beats together since they were kids. In his role as a Reality Center co-founder, Tarun brought his software-developer brother Pranab into the project to build the InTune software. It’s used both in-session and on your own after the session, which Tarun calls a “digital supplement” using personalized binaurals to re-establish nervous system entrainment after the experience. Vocal samples are recorded after you’ve been put into a meditative state and while talking about what brings you joy, so the custom binaural generated contains your highest vibrational states of being. A graph with the 12 emotional biomarkers are displayed on a projection screen before you, so as you speak in real time you can see data about what’s going on emotionally in your own subconscious mind. After that it’s time to get on a sound-wave table and have a full body experience of resting in your own frequency.

Tarun explained, “We’re making sure people that have no experience can achieve these states, which haven’t been available, especially in a personalized way. We’re really focused on making something fine tuned to your specific needs, which is why it’s called InTune. Our voice is a great biometric, it carries with it what you’re thinking, what you’re feeling.” The harmonic data is compared to the words being used, and clusters of information are tracked, which is what becomes the 12 emotional biomarkers. “On a very basic level we have different algorithms that find the fundamental frequency of the tones of your voice. You can say the same word 100 times and it might have a different tone depending on when you said it, how you’re feeling that day, how much sleep you got or what you’re goal state is,” he added about the customization. “We’re looking for the most harmonic parts of your statements, where that tonality is most aligned, that gives us a metric we can use to create instant, personalized biofeedback.”

There’s a delightful balance between science and esoteric philosophy in Reality Center’s approach to sessions, which are intended to empower clients’ psyches so they can make the changes needed to adjust reality to their preferences. Tarun described how our souls form on Earth with no instruction manual, thrown into the gameplay of the human experience. It can take many lifetimes to acquire learn the knowledge needed to get the best out of being here. “But we’re in a time in which we need dramatic shifts to happen quickly, so this is a tool to create agency for transformation,” he said. As kids, he and Pranab had turntables and were pushing Schumann Resonance standing wave binaural beats through their subwoofers to align themselves, calling themselves “neuro-DJs.” Tarun was clearly the right person to meet Don and put the founding team together, alongside combat veteran and commercial media director Jonathan Chia.

“After we forgive or let go, what do we actually want to wake up and do everyday now that those things aren’t holding us back?”

Treating veterans is a core function of Reality Center, which they’re able to do free of charge thanks to grant funding. After losing countless friends during and after his military service to drugs and suicide, Jonathan had a psychedelic experience that left him certain of life after death and solidified his mission to bring this experience to his fellow servicemen and women. Once the nervous system reset takes place, he explained, the experience of expanded consciousness and integration begins. “If you feel like you have to protect yourself all the time, you never really sleep that well and if you don’t sleep well you never get reset. We reset, expand then use the experience to elevate your life. We try to move people as fast as possible to the human performance side of it. After we forgive or let go, what do we actually want to wake up and do everyday now that those things aren’t holding us back?” There are countless reports from clients who have experienced that level of emotional release from a session.

All Reality Center clients have access to their session technician beyong their appointment to provide integration support, providing ongoing access to a community who’ve shared the experience that positively influences the state of neuroplasticity clients find themselves in. Technicians are extremely open-hearted and minded when it comes to helping clients integrate every aspect of their experience. “We don’t approach this from just a new age wellness perspective,” Pranab explained, “There’s a lot of science that goes into this, but also a lot of comfort. This is not a sterile, clinical building. We’re not trying to be anyone’s guru - we’re peers.”

Witnessing the peer-to-peer healing dynamic in action between Jonathan and 73-year-old client, veteran and original Source Family member Zarathustra Aquarian, opened up another dimension of Reality Center - the multigenerational collaboration powering the project. Born the same year as Don, Zarathustra lived through the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s and watched the cultural tides turn from the imprisonment of Timothy Leary in 1970 to the decriminalization of psilocybin in American cities 50 years later. They both lived through the technological revolution of computers and smartphones becoming ubiquitous, and even though Don developed the tech decades ago, he needed Millennial design and marketing to bring harmonic resolution therapy to its full iteration. Zarathustra is a computer scientist by training and he came to Reality Center looking for the deep relaxation and connection to his higher self that he gets from a sensory deprivation floatation tank.

“After working with John, I realized that sensory deprivation is a special case of my theory of sensory resonance, wherein all of the senses are given nothing instead of being synchronized together in a coherent experience as we do at the Reality Center,” said Don. “ Both, all or nothing seem to distract the normal mind from the clutches of the reticular activating system's survival mode that blocks access to those higher states of mind and assists in achieving altered or non-ordinary states of mind.” In many ways the experience of being put into harmonic resolution via light, sound and vibration stimulus is exactly the opposite of floating in a dark saltwater tank, yet both can yield psychedelic experiences. Don and his co-founders believe our consciousness can more readily separate from the physical body and experience a psychedelic-level of awareness with an entrained nervous system, which is why connecting with dead loved ones is so common.

In an expanded state of consciousness the veil between dimensions, including that of life and death, become thin. “The difference between your current state and ideal state is where suffering lies,” Tarun reminds us, and having an experience of consciousness beyond death is sometimes the only bridge needed to close the gap between one’s current and one’s ideal state.

We wrapped up at Reality Center with a final, albeit obvious, question: does anything strange ever happen? Stories began pouring out from Tarun and Pranab about equipment turning on when the power was out, glitches coinciding with moments of personal revelation, seeing beings in the room through closed eyes, and an endless list of synchronicities and coincidences. For instance, back-to-back clients with no exposure to each other will use the same word to describe their state of being. Apparently this usually happens in threes, like three consecutive clients who don’t know each other all being from the same town. It’s a rather flirtatious pattern of reality Terence McKenna might characterize as the universe nodding in approval.

Tarun thinks a synchronicity is just a vibrational correlation, which is precisely the type of data being generated by InTune and the nature of nervous system entrainment facilitated in the session. With all that vibrational correlation percolating in Reality Center’s Morphic field, of course they’re resonant with ongoing instances of correlation. Check out RealityMgmt.com and get InTune here.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

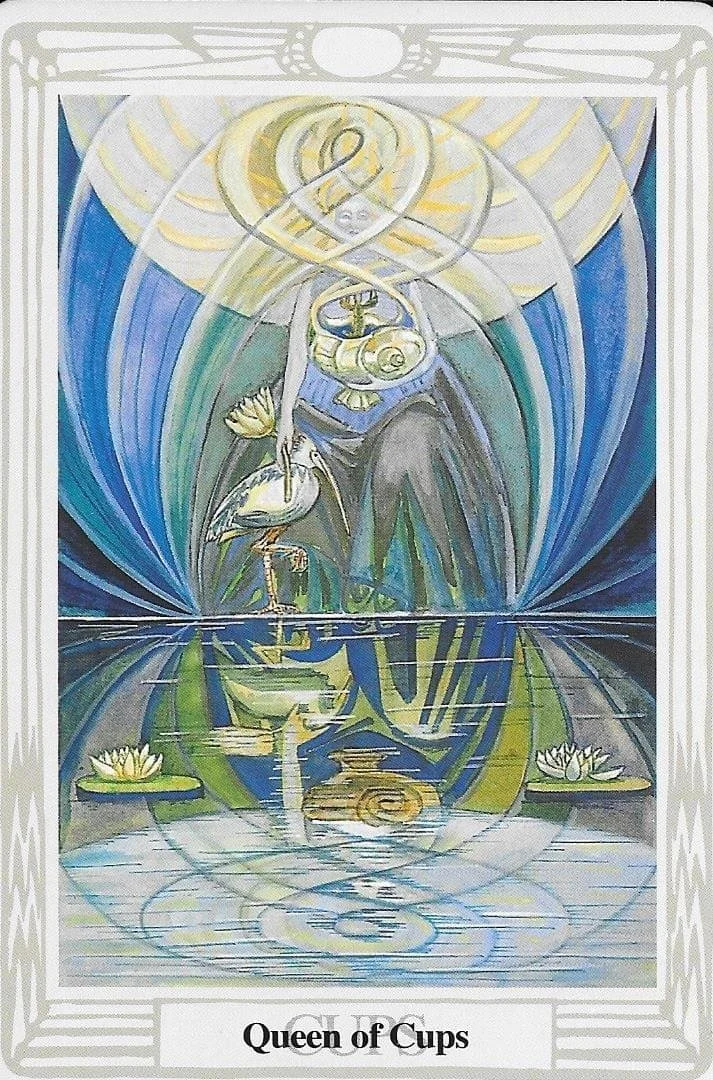

Queen of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 26, 2025

The Queen of Cups is the wateriest card in the deck and the quintessence of the element. She is the Mother enthroned, holding her precious womblike grail. She is both guarded and receptive…

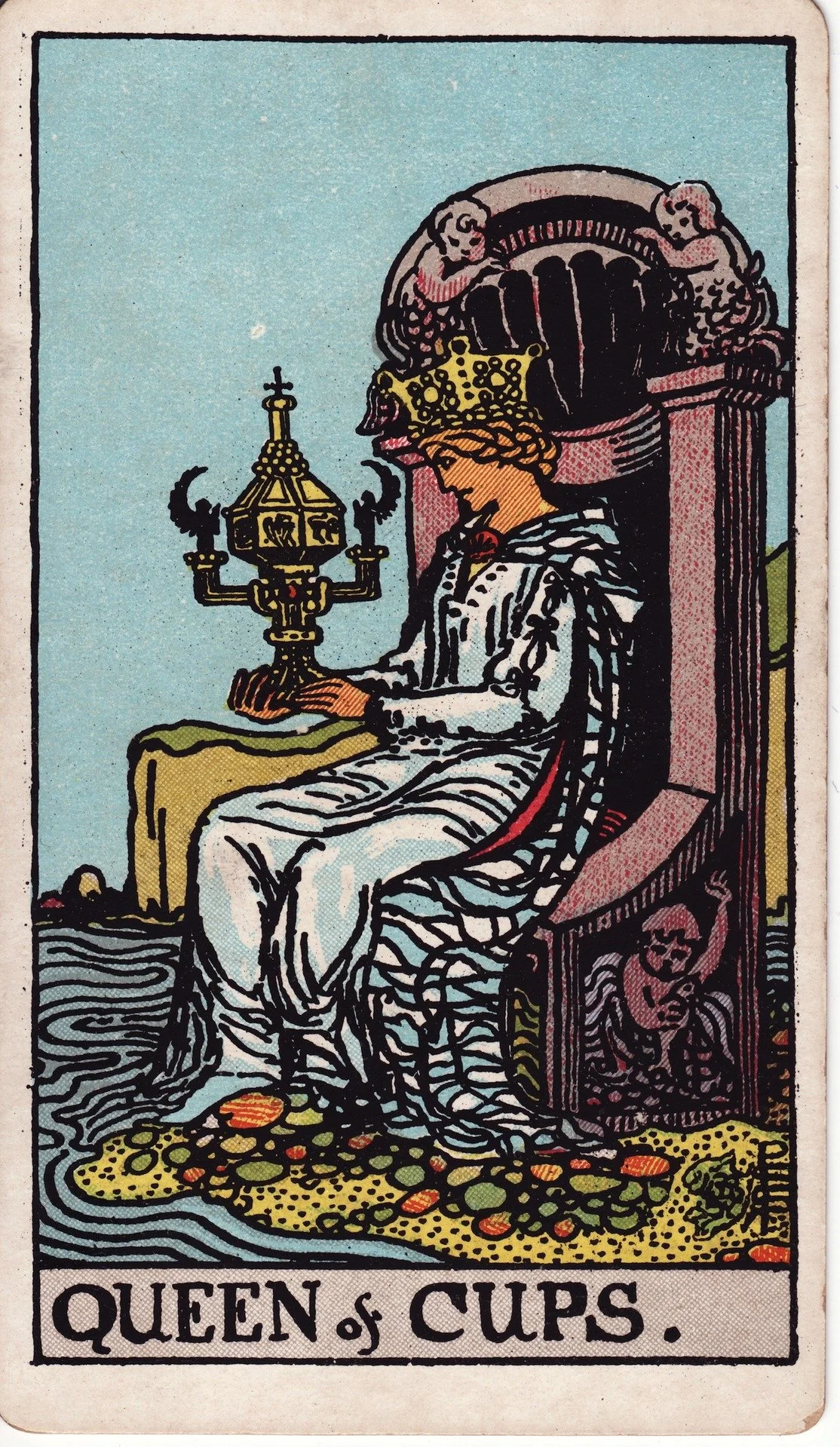

Name: Queen of Cups

Number: 2

Astrology: Cancer, Water of Water

Qabalah: He of He

Chris Gabriel July 26, 2025

The Queen of Cups is the wateriest card in the deck and the quintessence of the element. She is the Mother enthroned, holding her precious womblike grail. She is both guarded and receptive.

In Rider, we have a blonde Queen in a diaphanous gown that melds with the water at her feet. Her throne is adorned by cherubs and shells, and set upon a stony beach. The Cup she holds is closed and complex in its design. Like the Ark of the Covenant it is sealed and guarded by angels. It is topped by a cross and she looks intensely at it.

In Thoth, the Queen is barely visible; her skin is blue, and her face is obscured by the water which flows about her. She holds a lotus in one hand, and in the other, a large shelllike cup from which a little crustaceans peeks out. She is petting an Ibis. The pool she stands in has two lotuses.

In Marseille, the Queen is blonde, she looks upon her sealed cup and holds a wavy dagger, ready to defend what is hers.

As the Queen of Cups is given to Cancer, we see the contradictory nature of the card: a cup is meant to be open, to receive water and wine, but the crab of the zodiac is armored and defensive, so her cup is closed off.

She is protecting what is hers. The Mother who is fiercely protective of her children, or in a negative aspect, a smothering, over protective, and controlling matriarch. She is a lover who sits ready with her dagger to ward off those who would enter her heart or womb.

An image that arises in Thoth is that of the woman who “loses herself” in love, whether romantic or maternal. Her identity and individuality is secondary to her role. These are universal problems: how do we exist as individuals when surrounded by others? When does defensiveness veer into alienation? How do we let the right people in and keep the wrong people out?

These are the same issues that concern the Chariot, though on a smaller scale. He protects the nation, but the Queen of Cups, another form of Cancer, protects herself and her family. These are the same energies operating on different wavelengths.

Each Queen depicted seems to have a different solution. Rider holds her Cup tightly with both hands - she keeps it sealed, and under constant surveillance. Marseille holds it with one hand, but is ready with a dagger in the other to keep it safe. Thoth hides and disguises herself, she keeps it open, but with a guardian.

Each solution comes with its own problem, but they all lead the queen to become a “homebody”, a crab happy to live in the same pool forever. Their attention is fixed so strongly upon what is theirs and how to keep it safe that they fail to explore. This is clear when we compare with the opposite card, the Capricornian Queen of Disks, who wants to rise and gain greater power over more space.

When we pull this card, we may be called on to protect what is ours, to mother and care for someone. It may also directly indicate a Cancer that we know.

The Sea and the Wind That Blows

E.B. White July 24, 2025

Waking or sleeping, I dream of boats - usually of rather small boats under a slight press of sail. When I think how great a part of my life has been spent dreaming the hours away and how much of this total dream life has concerned small craft, I wonder about the state of my health, for I am told that it is not a good sign to be always voyaging into unreality, driven by imaginary breezes…

Sailing a Dory, Winslow Homer. 1880.

A meditation on ageing and an elegy for passion, as E.B. White approached his twilight years in 1963 he looked back on his defining love in this piece first published in ‘Ford Times’. What begins as a dream of boats becomes a study of memory, solitude, and the strange pull of the water. Written as a way to say goodbye as he retire from his hobby, White questions whether he can even leave behind that which seems to define him - his strange, lifelong entanglement with the sea.

E. B. White July 24, 2025

Waking or sleeping, I dream of boats - usually of rather small boats under a slight press of sail. When I think how great a part of my life has been spent dreaming the hours away and how much of this total dream life has concerned small craft, I wonder about the state of my health, for I am told that it is not a good sign to be always voyaging into unreality, driven by imaginary breezes.

I have noticed that most men, when they enter a barber shop and must wait their turn, drop into a chair and pick up a magazine. I simply sit down and pick up the thread of my sea wandering, which began more than fifty years ago and is not quite ended. There is hardly a waiting room in the East that has not served as my cockpit, whether I was waiting to board a train or to see a dentist. And I am usually still trimming sheets when the train starts or the drill begins to whine. If a man must be obsessed by something, I suppose a boat is as good as anything, perhaps a bit better than most. A small sailing craft is not only beautiful, it is seductive and full of strange promise and the hint of trouble. If it happens to be an auxiliary cruising boat, it is without question the most compact and ingenious arrangement for living ever devised by the restless mind of man - a home that is stable without being stationary, shaped less like a box than like a fish or a bird or a girl, and in which the homeowner can remove his daily affairs as far from shore as he has the nerve to take them, close-hauled or running free -parlor, bedroom, and bath, suspended and alive.

Men who ache allover for tidiness and compactness in their lives often find relief for their pain in the cabin of a thirty-foot sailboat at anchor in a sheltered cove. Here the sprawling panoply of The Home is compressed in orderly miniature and liquid delirium, suspended between the bottom of the sea and the top of the sky, ready to move on in the morning by the miracle of canvas and the witchcraft of rope. It is small wonder that men hold boats in the secret place of their mind, almost from the cradle to the grave.

Along with my dream of boats has gone the ownership of boats, a long succession of them upon the surface of the sea, many of them makeshift and crank.

Since childhood I have managed to have some sort of sailing craft and to raise a sail in fear. Now, in my sixties, I still own a boat, still raise my sail in fear in answer to the summons of the unforgiving sea.

Why does the sea attract me in the way it does: Whence comes this compulsion to hoist a sail, actually or in dream? My first encounter with the sea was a case of hate at first sight. I was taken, at the age of four, to a bathing beach in New Rochelle. Everything about the experience frightened and repelled me: the taste of salt in my mouth, the foul chill of the wooden bathhouse, the littered sand, the stench of the tide flats. I came away hating and fearing the sea. Later, I found that what I had feared and hated, I now feared and loved.

I returned to the sea of necessity, because it would support a boat; and although I knew little of boats, I could not get them out of my thoughts. I became a pelagic boy. The sea became my unspoken challenge: the wind, the tide, the fog, the ledge, the bell, the gull that cried help, the never-ending threat and bluff of weather.

Once having permitted the wind to enter the belly of my sail, I was not able to quit the helm; it was as though I had seized hold of a high-tension wire and could not let go.

I liked to sail alone. The sea was the same as a girl to me I did not want anyone else along.

Lacking instruction, I invented ways of getting things done, and usually ended by doing them in a rather queer fashion, and so did not learn to sail properly, and still cannot sail well, although I have been at it all my life. I was twenty before I discovered that charts existed; all my navigating up to that time was done with the wariness and the ignorance of the early explorers. I was thirty before I learned to hang a coiled halyard on its cleat as it should be done. Until then I simply coiled it down on deck and dumped the coil. I was always in trouble and always returned, seeking more trouble. Sailing became a compulsion: there lay the boat, swinging to her mooring, there blew the wind; I had no choice but to go. My earliest boats were so small that when the wind failed, or when I failed, I could switch to manual control-I could paddle or row home. But then I graduated to boats that only the wind was strong enough to move. When I first dropped off my mooring in such a boat, I was an hour getting up the nerve to cast off the pennant. Even now, with a thousand little voyages notched in my belt, I still I feel a memorial chill on casting off, as the gulls jeer and the empty mainsail claps.

The Cat Boat, Edward Hopper. 1922.

Of late years, I have noticed that my sailing has increasingly become a compulsive activity rather than a source of pleasure. There lies the boat, there blows the morning breeze-it is a point of honor, now, to go. I am like an alcoholic who cannot put his bottle out of his life. With me, I cannot not sail. Yet I know well enough that I have lost touch with the wind and, in fact, do not like the wind any more.

It jiggles me up, the wind does, and what I really love are windless days, when all is peace. There is a great question in my mind whether a man who is against wind should longer try to sail a boat. But this is an intellectual response-the old yearning is still in me, belonging to the past, to youth, and so I am torn between past and present, a common disease of later life.

When does a man quit the sea? How dizzy, how bumbling must he be? Does he quit while he's ahead, or wait till he makes some major mistake, like falling overboard or being flattened by an accidental jibe? This past winter I spent hours arguing the question with myself. Finally, deciding that I had come to the end of the road, I wrote a note to the boatyard, putting my boat up for sale. I said I was "coming off the water." But as I typed the sentence, I doubted that I meant a word of it.

If no buyer turns up, I know what will happen: I will instruct the yard to put her in again-"just till somebody comes along." And then there will be the old uneasiness, the old uncertainty, as the mild southeast breeze ruffles the cove, a gentle, steady, morning breeze, bringing the taint of the distant wet world, the smell that takes a man back to the very beginning of time, linking him to all that has gone before. There will lie the sloop, there will blow the wind, once more I will get under way. And as I reach across to the black can off the Point, dodging the trap buoys and toggles, the shags gathered on the ledge will note my passage. "There goes the old boy again," they will say. "One more rounding of his little Horn, one more conquest of his Roaring Forties." And with the tiller in my hand, I'll feel again the wind imparting life to a boat, will smell again the old menace, the one that imparts life to me: the cruel beauty of the salt world, the barnacle's tiny knives, the sharp spine of the urchin, the stinger of the sun jelly, the claw of the crab.

E.B. White (1899–1985) was an American essayist, poet, and author best known for Charlotte’s Web and his nearly 60 year career as a writer, then contributing editor, for The New Yorker, from its founding until his death.

How Old Is The Sky? A Brief History Across Philosophies

Sander Priston July 22, 2025

Despite the ancient sounding ring to this rather abstract question, the first sign of an attempted answer in Western philosophy came only with the Moderns. Not the Stoics with their eternal return, nor the Christians with their metaphysical hesitations, it wasn’t until the 17th and 18th Centuries that two very different philosophers emerged with two very different answers to the question…

Sander Priston July 22, 2025

Despite the ancient sounding ring to this rather abstract question, the first sign of an attempted answer in Western philosophy came only with the Moderns. Not the Stoics with their eternal return, nor the Christians with their metaphysical hesitations, it wasn’t until the 17th and 18th Centuries that two very different philosophers emerged with two very different answers to the question.

The first came from a bishop named James Ussher, who in 1650 published Annales Veteris Testamenti - a chronology of the world using the Bible as a historical record. In this, he declared that the creation of the world — including the heavens and sky — occurred on

Sunday, 23 October, 4004 BC, at around 6:00 PM.

It is a strangely precise estimate for a first try, and implied the sky was roughly 6,000 years old in his time. This young sky abides by the Biblical notion that the earth and its heavens were invented for humanity’s sake.

65 years later, a natural philosopher watching molten iron cool in a furnace proposed a radically different answer. Edmond Halley, who famously predicted the date a comet would return decades before it did, used the salinity of the oceans and the rate of cooling of celestial bodies to estimate the sky's age.

In a 1714–1716 issue of the Philosophical Transactions, Edmond Halley presented what we now call the ‘salt clock’ method—using the rate of salt accumulation in the oceans to estimate the age of the Earth—and by implication, the atmosphere and sky. He declared that, “The sky is 75,000 years old. At least.”

Though Halley fell short of a definitive number like Ussher’s, he was among the first to suggest that a measurable, natural process could give us an empirical age of the cosmos. This kicked off the inquiry which led us to our most up-to-date estimate of ~13.8 billion years, reached through a combination of Cosmic microwave background radiation measurements (from missions like Planck and WMAP), Hubble’s law (expansion rate of the universe), and standard cosmological models (like ΛCDM).

Together, Ussher and Halley represent a major philosophical clash at the dawn of modern science. Ussher’s precise, scripture-based chronology reflected a worldview where the sky was young and created for humanity, while Halley’s naturalistic measurements hinted at a vast, ancient universe waiting to be understood through observation and reason.

Looking beyond Western thought, however, we find many interesting and creative attempts by philosophers at dating the age of the sky. In Hindu Cosmology, for example, the sky is 155.52 trillion years old.

In the Puranas and Mahabharata, important Hindu religious texts, time is structured into immense cosmic cycles. A kalpa (a "day of Brahma") is 4.32 billion years. A full cycle (including nights, years, lifetimes of Brahma) adds up to trillions of years. The current sky is said to be in the 51st year of Brahma, which places the age of this cycle of the universe at around 155.52 trillion years. The sky then has an age but no clear origin.

Madame Blavatsky, the 19th-century Russian-born mystic and founder of Theosophy, drew heavily on ancient Hindu cosmology and esoteric traditions to propose her own occultist answer, centered on the concept of “Manvantaras” — vast cosmic cycles. These cycles are measured in millions to billions of years, though Blavatsky’s calculations are symbolic and allegorical rather than scientific.

In her major work, The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky described Earth’s spiritual and physical evolution as unfolding through seven Root Races, or stages in humanity’s development, each corresponding metaphorically to vast astrological ages governed by star-beings. The Hindu-inspired cycles she describes imply a sky that is billions of years old, with a Mahayuga (Great Age) lasting 4.32 million years and a Day of Brahma lasting 4.32 billion years (1,000 Mahayugas).

Some Chinese Daoist alchemical texts, especially those concerned with immortality and the “Great Year” (da nian), describe time as cyclical in units of 129,600 years — tied to astronomical and numerological systems. The Taiyi Shengshui (The One Gave Birth to Water) and works like Huainanzi talk of sky and earth co-arising from primal qi, but some traditions suggest skies are reborn every great cycle. So the sky has a reset button, and its age is the circumference of a cosmic breath: 129,600 years.

In Zoroastrian cosmology, the universe is laid out across a 12,000-year timeline, divided into 4 epochs of 3,000 years. The sky (or firmament) was created in the second epoch, after the spiritual world but before humanity. So the sky is roughly 9,000 years old in this system – it was built in Year 3,000 and will collapse by Year 12,000.

“The sky, to our eyes, may rise, set, storm, and clear but this is theater, not ontology. The real sky — if such a thing exists — cannot age, because it does not become. It simply is.”

Our question, then, was considered across ancient cultures so why did no answer appear in Western thought prior to the Modern Period? For the Ancients, the reason is likely that they didn’t separate the sky from the cosmos. Asking “how old is the sky?” was like asking “How old is the stage before the play?” Time was something the sky measures, not something the sky experiences. As the realm of gods, stars, or divine harmony, giving it a number would be like putting a birthday on Zeus.

We see this in Plato, for whom the sky is not in time — time is in the sky; it is the first clock. Its age is synonymous with the very concept of age. For the Stoics, the sky has died a thousand times and will live again (ekpyrosis). It has no age because it is incapable of ceasing to be. It is a loop, not a line.

In many mythologies, the sky is not a natural object, but a deliberate covering — a veil stretched taut by the gods to conceal the raw machinery of existence. In Babylonian myth, Marduk slays the chaos-dragon Tiamat and stretches her body across the heavens to form the sky — a grim, cosmic tarp made of vanquished disorder. In Genesis, the firmament is created to divide the waters above from the waters below — a protective dome that makes human life possible. The sky is a curtain drawn for our benefit.

Gnostic texts, like On the Origin of the World and Apocryphon of John, consider the sky a deception – a rotating dome ruled by false gods (archons) who trap souls below it. The sky’s age is the length of our captivity — its number is how long we’ve been asleep.

Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), a cryptographer-monk-mystic, wrote about celestial intelligences controlling the world in 800-year periods, rotating like gears — a secret calendar with no age, but a coded rhythm

Some of the most interesting philosophies of the sky come from pre-Socratic philosophers. Their fragmentary insights, handed down in cryptic scraps, do not ask for an age, but rather what the sky is, and how it comes to be. They all answered our question in their own way — not with numbers, but with metaphors of fire, breath, rhythm, and ruin.

For Parmenides, the sky had no age. All that exists is Being, and Being does not change. Time, movement, growth, decay — these are illusions conjured by unreliable senses. If we trust only reason, we must conclude that what is, always was and always will be. There is no birth or death, past or future. Only the eternal, seamless Now. If the sky is, then it has no age, because age presumes change — a before and after. But there is no before and after in truth.