Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094137561?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Greenwich Village Sunday clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Maeshowe, Sound, and Viking Runes (Artefact II)

Ben Timberlake June 17, 2025

Maeshowe is a Neolithic chambered burial complex on the Orkney Islands, an archipelago to the north of Scotland that is a floating world of midnight suns and brutal, dark winters. The tomb overlooks the Lochs of Harry and Stenness. On the narrow spit of land that separates the two lochs is The Ring of Brodgar, an ancient stone circle. It is nothing to look at from the outside - bored sheep munching salty grass on a small mound — but inside is one of the finest prehistoric monuments in the world…

WUNDERKAMMER #2

Artefact No: 2

Location: Maeshow, Orkney Islands, Scotland

Age: 5,000 years

Ben Timberlake June 17, 2025

Maeshowe is a Neolithic chambered burial complex on the Orkney Islands, an archipelago to the north of Scotland that is a floating world of midnight suns and brutal, dark winters. The tomb overlooks the Lochs of Harry and Stenness. On the narrow spit of land that separates the two lochs is The Ring of Brodgar, an ancient stone circle. It is nothing to look at from the outside - bored sheep munching salty grass on a small mound — but inside is one of the finest prehistoric monuments in the world.

The tomb’s structure is cruciform: a long passageway some 15m long, a central chamber, with three side-chambers. The main passageway is orientated to the southwest. Building began on the site around 2800BC. It is a work of monumental perfection: each wall of the long passageway is formed of single slabs up to three tons in weight; each corner of the main chamber has four vast standing stones; and the floors, walls and ceilings of the side-chambers are made from single stones. Smaller, long, thin slabs make up the rest of the masonry. They are fitted with unfussy but masterful precision in the local sandstone. It is even more impressive when you realize that these stones were cut and shaped thousands of years before the invention of metal tools. It is estimated to have taken 100,000 hours of labor to construct.

The interior chamber of Maeshowe, illuminated by the sun of the Winter Solstice.

Maeshowe sits within one of the richest prehistoric landscapes in Europe. The four principal sites are two stone circles - the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness - Maeshowe and the perfectly preserved Neolithic village of Skara Brae. These sites are within a further constellation of a dozen Neolithic and Bronze Age mounds, and other solitary standing stones.

Aligned within this landscape like a vast sundial, Maeshowe is sighted so as to tell the time just once a year, at midwinter. For a couple of weeks at either side of the winter solstice the sun sets to the southwest and the rays of the run enter down the long passage and illuminate the wall at the back of the end chamber. And this midwinter sun, at the zenith of its year, sets perfectly above the Barnhouse Stone some 700m away. The spectacle can be viewed live online every year.

Maeshowe and its sister sites are open to the public and well worth a visit. Because of their remote location they get a fraction of the visitor numbers similar sites receive. There is something deeply penitential about a visit there. The long passage is only a meter and a half tall and archaeologists believe it was designed this way to force people to bow and submit as they walked towards the center of the complex.

The Barnhouse Stone, on the left, aligns perfectly with the entrance to Maeshow, the mound on the right, so that on the day of midwinter, the sun sets above the stone and into the entrance to Maestowe.

“The frequency for Maeshowe was a drum being beaten at 2hz creating an infrasonic frequency that, although inaudible to us, could be felt as a physical or psychological sensations such as dizziness, raised heartbeat, and flying sensations. And that’s before we factor in the drugs.”

As much as Maeshowe is a place of the dead, it is also a temple to sound. Dr Aaron Watson, an honorary fellow from Exeter University, spent a number of years researching the effects of sound at different prehistoric sites. He found that specific pitches of vocal chants and different types of drumming could produce strange, amplified sound effects known as ‘standing waves’. These are very distinct areas of high and low intensity which seem to bear no relation to the source of the sound. In the case of Maeshowe, a drummer in the central chamber could be muted to those standing nearby but the sound would be vastly magnified in the side chambers. The acoustics are so powerful that the Neolithic builders must have known what they were doing when they built the structure. A recessed niche in one of the tunnel walls allowed a large stone to be dragged into the passageway blocking the passage and amplifying the sound.

Even more impressively was the possibility that Maeshowe displayed elements of the Helmholtz Effect - a phenomenon of air resonance in a cavity - but on a much larger scale. The frequency for Maeshowe was a drum being beaten at 2hz creating an infrasonic frequency that, although inaudible to us, could be felt as a physical or psychological sensations such as dizziness, raised heartbeat, and flying sensations. And that’s before we factor in the drugs. These European prehistoric societies made ample use of regular magic mushrooms and the red-and-white spotted Fly Agaric. To the Neolithic visitors the acoustics effects of Maeshowe alone must have been powerful but to combined with hallucinations it must have been one of the most profound and life changing experiences of their lives.

The tomb was rediscovered in 1861. I write ‘rediscovered’ because when the Victorian antiquarians began to clear soil and debris from the inner chambers, they came across evidence that they were not the first ones there since prehistoric times: the walls were adorned with Viking runes.

We have a very good idea who these Vikings were thanks to the Orkneyinga Saga, a medieval narrative history document woven through and embellished with myths. There appear to be two sets of culprits. Firstly, in 1151, a group of Viking Crusaders led by Earl Rognvald on their way to the Holy Land. Then, a couple years later - Christmas 1153 to be precise - a band of Viking looters on a raid led by Earl Harald.

The Norse traditionally held such ancient places with dread and it is not known what drove them to risk their mortal souls and enter the mound: a terrible storm is mentioned, but it may have been the legends of treasure too. The saga records that two of the Earl Rognvald’s men went mad with fear of the mythical Hogboon, from Old Norse hiagbui, or mound-dweller.

There are some 30 runes in Maeshowe, the largest collection outside Scandinavia. Here is a sample:

Crusaders broke into Maeshowe. Lif the earl's cook carved these runes. To the north-west is a great treasure hidden. It was long ago that a great treasure was hidden here. Happy is he that might find that great treasure.

Ofram, the son of Sigurd carved these runes.

Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes.

Thatir the weary Viking came here.

Ingigerth is the most beautiful of all women (carved beside a picture of a slavering dog).

Thorni fucked. Helgi carved.

All too often historians and archaeologists concern themselves with official inscriptions left by kings and emperors and other fevered egos but I don’t think that anything quite says ‘Look on my works ye mighty and despair’ than a Viking warrior getting laid and then recording it on the rock of ages with his axe.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094145452?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Soy Cuba clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Larry Levan Playlist

Archival 1987

Larry Levan was an influential American DJ who defined what modern dance clubs are today. He is most widely renowned for his long-time residency at Paradise Garage, also known as “Gay-Rage”, a former nightclub at 84 King Street in Manhattan, NY.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094123512?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Jack Kornfield clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Death (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 14, 2025

Death is undoubtedly the most feared card in the deck. He is a skeleton looking down at the bodies and souls of the dead below. While this card pertains to mortality itself, we shall see that death is far more than the failure of our bodies…

Name: Death or Nameless

Number: XIII

Astrology: Scorpio

Qabalah: Nun, a Fish

Chris Gabriel June 14, 2025

Death is undoubtedly the most feared card in the deck. He is a skeleton looking down at the bodies and souls of the dead below. While this card pertains to mortality itself, we shall see that death is far more than the failure of our bodies.

In Rider, Death is depicted Biblically, as the horseman on the pale steed.

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.

Revelation 6:8

The skeletal rider is clad in black armor with a red plume atop his helmet. He holds aloft a black flag emblazoned with a white rose, a symbol of purity. His horse is pale white with red eyes. Before him a bishop prays, a child kneels, his mother swoons, and a king lays dead, his crown fallen. Behind them is an island, a ship, and, on the horizon, the Sun, that sets between the two towers featured in the Moon.

In Thoth, Death is a black skeleton wearing the Atef crown of Osiris. He weaves the karmic tapestry of souls before him with his scythe. Above him is the phantom of an Eagle, below there is a serpent and a scorpion, all symbols of Scorpio, and a fish to symbolize Nun. This is the Grim Reaper.

In Marseille, we have a notably nameless card, the only one in the deck. Here Death is a skeletal Grim Reaper in a field of hands, feet, bones, and two decapitated heads. One is crowned, the other is shaggy.

A primary image that arises is that of the dead king, a symbol which Diogenes the Cynic expresses best. Alexander, having heard that Diogenes was the wisest man in the world, came to hear his wisdom. When he arrived, Diogenes was digging through the waste of his trash can home. Alexander asked him what he was doing, to which he replied “I am trying to distinguish the bones of your father from those of a slave.”

As Shakespeare says, “Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots. Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service—two dishes, but to one table. That’s the end.”

Death is the great equalizer: beneath masks and costumes, beautiful and ugly flesh, lays a pale skeleton. The skull is a profound truth, and death’s head has always been used to terrify. Nearly every ancient culture revered it, pirates raised it as their flag, even today American police officers wear it on their uniforms.

Death in occultism, however, is more akin to the death of Paul, who says “I die daily”. The Scorpion willingly kills itself when surrounded by flames. This card invites us to “Die”, transform our body through terrifying alchemical processes and, like the white flower, be made purer. Our essence is distilled through this continual cycle of life and death. The given number of 13, an unlucky number, signifies this very thing. After the 12 hours, the 12 months, the 12 signs of the Zodiac, what comes next? What comes after the end?

When we pull this card, we must not be afraid. Instead, willingly put an end to what is limiting you,nand to the stilted, decaying structures that you cling to. People spend their whole lives avoiding change and, in doing so, die long before their body. When we decide to shed our skin like the serpent, we can have absolute confidence that we are becoming a stronger, greater version of ourselves.

When we outgrow our old life, we must die and be born again.

Film

<div style="padding:53.33% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094132387?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Playtime clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

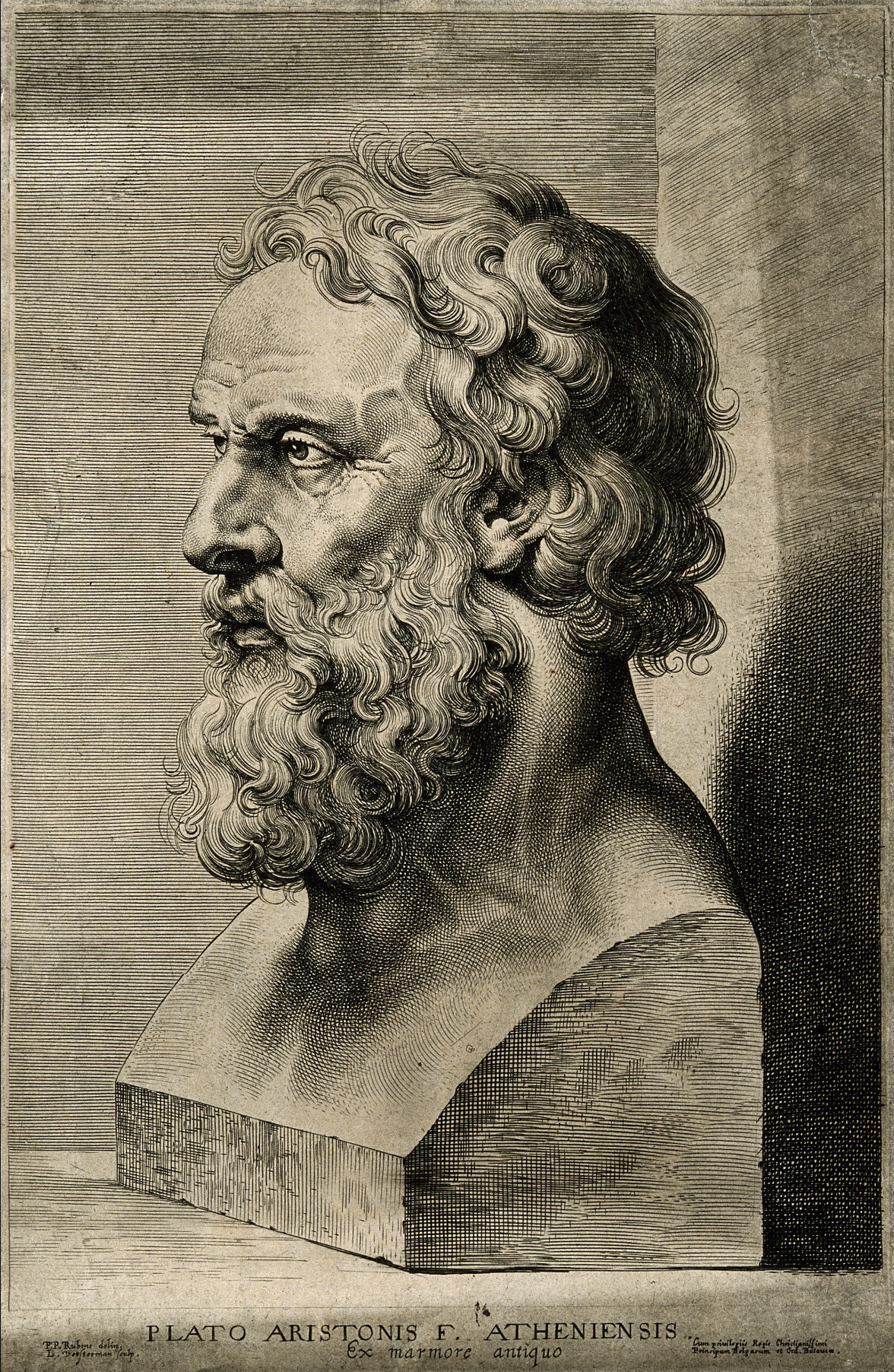

Footnotes to Plato (c.428-347BC)

Nicko Mroczkowski June 11, 2025

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name…

Rafael's School of Athens, 1511.

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name.

In this flourishing new culture, thinkers began to try and understand the world in a more organised way. From this, Western philosophy was born, and science came along with it. These thinkers asked themselves: what is the world made of, and how does it work? This was not a new question, most likely every culture before had asked it in some way, but what made the Ancient Greeks unique was their systematic approach. Because they also asked a secondary question, which, arguably, is still the starting point of any scientific inquiry: what is the correct way to talk about what something is?

L. Vosterman, after Rubens. c. 1620.

Each of the very first philosophers answered this question with one thing: ‘substance’, or stuff. They believed that the right way to understand the world is in terms of a single type of matter, which is present in different proportions in everything that exists. Thales of Miletus, perhaps the earliest Greek philosopher, believed that all things come from water; solid matter, life, and heat are all special phases of the same liquid. For him, then, the true way to talk about an apple, for example, is as a particularly dense piece of moisture. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything is made of fire; all existence is in flux, like the dancing flame, of which an apple is a fleeting shape.

We don’t know much more about these thinkers, as not much of their work survives; most of the accounts we have are second hand. We only know for sure that each proposed a different ultimate substance that everything is made out of. Then, a little while later, along came a philosopher called Plato.

Despite its prominence, ‘Plato’ was actually a nickname meaning ‘broad’ – there is disagreement about its origin, but the most popular theory is that it comes from his time as a wrestler. His real name is thought to have been ‘Aristocles’. Whatever he was really called, Plato changed everything. Instead of arguing, like his predecessors, for a different kind of ultimate substance, he observed that substance alone is not enough to explain what exists: there is also form. In other words, he more or less invented the distinction between form and content.

One could spend a lifetime analysing these terms, and there are whole volumes of art and literary theory that address their nuances; but it’s also a common-sense distinction that we use every day. The form of something is its shape, structure, composition; the content, or substance, is the stuff it’s made of. So the form of an apple is a sweet fruit with a specific genetic profile, and its content is various hydrocarbons and trace elements. The form of a literary work is its style and composition – poetry or prose, past or present tense, first- or third-person, etc. – and its content is its subject matter, what it describes and what happens in it.

An attempt at a classification of the perfect form of a rabbit. (1915)

We can already see Plato’s influence on modern knowledge in these examples. The correct way to talk about something, for him, was primarily in terms of its form, and only secondarily in terms of its substance. This is still the case for us today. There is a powerful justification for this preference: it allows us to talk about things generally. This is basically the foundation of any science; we would get absolutely nowhere if we only analysed particular individuals. There are just too many things out there. No two animals of the same species, for example, will ever have exactly the same make-up – even if they’re clones. They have eaten different things, had different experiences; they also, quite frankly, create and shed cells so rapidly and unpredictably that differences in their substance are inevitable. What they do have in common, though, is their anatomy, behaviour, and an overall genetic profile that produces these things.

Forms are peculiar, however, because they don’t exist in the same way as substances do. While there are concrete definitions of substances, the same cannot be said for forms. There are, for example, no perfect triangles in existence, and we could probably never create one – zoom in enough, and something will always be slightly out of place. So how did Plato come up with the idea of something that can never be experienced in real life? The answer is precisely because of things like triangles. Mathematics, and especially geometry, is the original language of forms, and it can describe a perfect triangle or circle, even though one may never exist. The success of mathematical inquiries in Plato’s time allowed him to recognise that the concept of forms which worked in geometry can be applied to understand the world more generally.

Forms are perfect specimens of imperfect things, are exemplars, or things we aspire to – they are the way things ought to be, in a perfect world. ‘Form’ in Plato’s work is also sometimes translated as ‘idea’ or ‘ideal’. And so, Plato’s answer to the question of how to conduct scientific inquiry was this: the correct way to talk about something is in terms of how it should be. Despite our imperfect world, rational thinking – the capacity of the human mind for grasping things like mathematical truths – can do this, and that’s what sets human beings and their societies apart from the rest of nature.

Perfect Platonic Solids

It gets a little strange from this point on: Plato believes that forms really exist, but in a separate, perfect world. Our souls start out there and then make their way to the material world to be born, but still have implicit knowledge of their original home, and this is where reason originates. Improbable, yes, but not completely absurd. Plato was clearly trying to explain, to a society that was just beginning to understand the importance of perfect knowledge, how it could exist in our imperfect world of change and difference. Two millennia later, Kant would show that it’s due to the way the human mind is structured, but we don’t really know how this happened either.

Really, we’re still playing Plato’s game. The basic realisation that to know the world, we must study the general and the perfect, and ignore the non-essential characteristics of particular individuals – this is his legacy. Of course, this way of thinking is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it can be hard to grapple with; it’s so fundamental that we take it for granted. But what we call knowledge today would not be possible at all without it. Seeing this, we can imagine what the influential British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead meant when he wrote that ‘the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Nicko Mroczkowski

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1092213848?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Acting Shakespeare- The Two Traditions clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

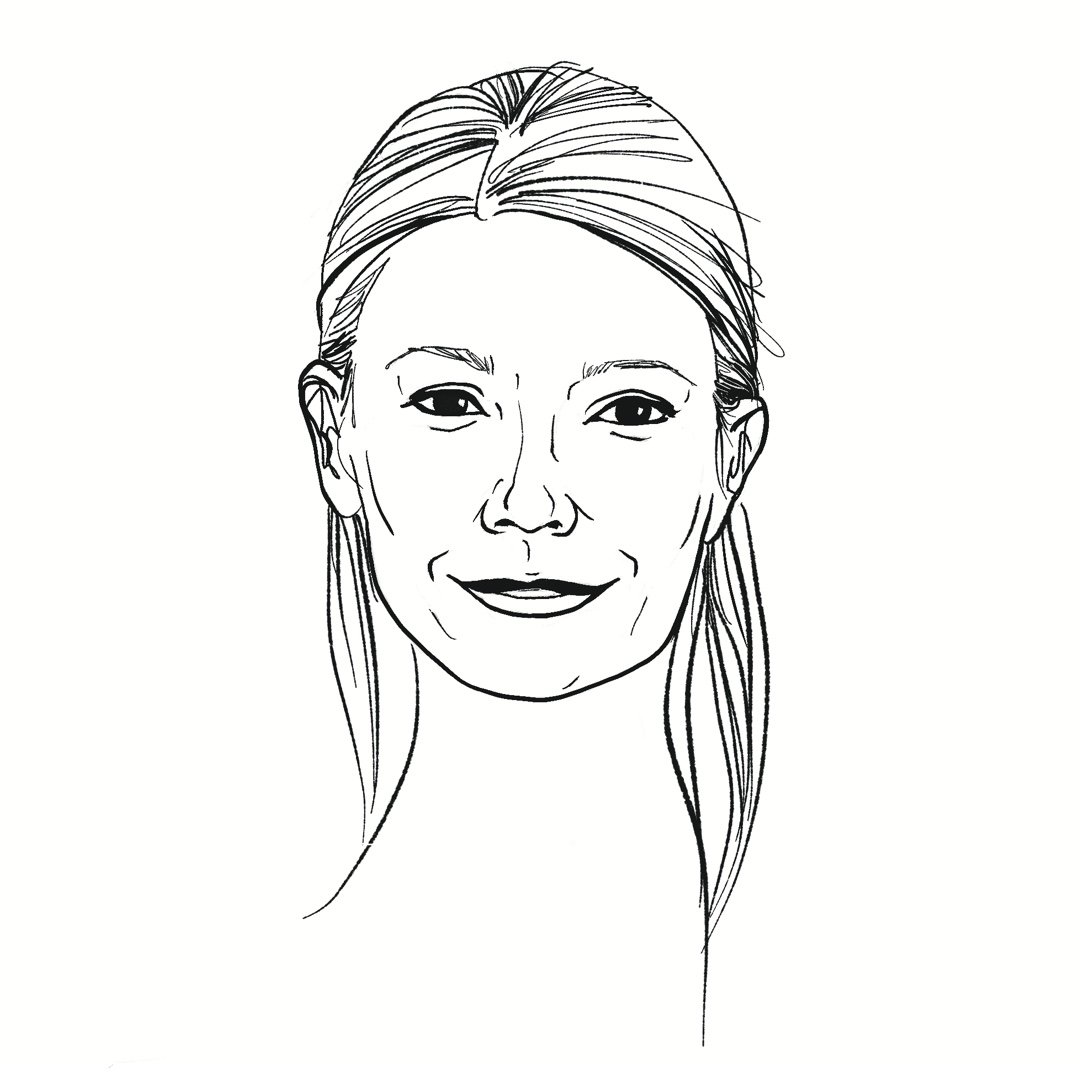

Gwyneth Paltrow

1h 24m

6.11.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Gwyneth Paltrow about adhering to social expectations.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/3rouuii2/widget?token=ac059634f4da574e8bfdbd9b30cdfd90" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1092236340?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Portrait of Jennie clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

On Photography (Excerpt)

Susan Sontag June 10, 2025

To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store…

Portraits in Life and Death, Peter Hujar. 1976.

When Susan Sontag released ‘On Photography’ in 1977, itself a collection of essays written in the preceding four years, it announced a new era in thinking about the medium. In the near fifty years since, it has become easy to overlook how radical Sontag’s ideas were for they have been absorbed so readily into the common theoretical understanding of photography we struggle to understand photography outside of her thinking. The book considers photography as a somewhat violent act that fosters a voyeuristic relationship with the world, separate from the reality it purports to capture. Yet the work is not inherently critical of the medium, instead it asks us to consider the power of depiction that the camera gives us, and to weild the tool with respect and compassion.

Susan Sontag June 10, 2025

To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store. In Godard's Les Carabiniers (1963), two sluggish lumpen-peasants are lured into joining the King's Army by the promise that they will be able to loot, rape, kill, or do whatever else they please to the enemy, and get rich. But the suitcase of booty that Michel-Ange and Ulysse triumphantly bring home, years later, to their wives turns out to contain only picture postcards, hundreds of them, of Monuments, Department Stores, Mammals, Wonders of Nature, Methods of Transport, Works of Art, and other classified treasures from around the globe. Godard's gag vividly parodies the equivocal magic of the photographic image. Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognize as modern. Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.

To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge-and, therefore, like power. A now notorious first fall into alienation, habituating people to abstract the world into printed words, is supposed to have engendered that surplus of Faustian energy and psychic damage needed to build modern, inorganic societies. But print seems a less treacherous form of leaching out the world, of turning it into a mental object, than photographic images, which now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the present. What is written about a person or an event is frankly an interpretation, as are handmade visual statements, like paintings and drawings. Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.

Photographs, which fiddle with the scale of the world, themselves get reduced, blown up, cropped, retouched, doctored, tricked out. They age, plagued by the usual ills of paper objects; they disappear; they become valuable, and get bought and sold; they are reproduced. Photographs, which package the world, seem to invite packaging. They are stuck in albums, framed and set on tables, tacked on walls, projected as slides. Newspapers and magazines feature them; cops alphabetize them; museums exhibit them; publishers compile them.

For many decades the book has been the most influential way of arranging (and usually miniaturizing) photographs, thereby guaranteeing them longevity, if not immortality-photographs are fragile objects, easily torn or mislaid-and a wider public. The photograph in a book is, obviously, the image of an image. But since it is, to begin with, a printed, smooth object, a photograph loses much less of its essential quality when reproduced in a book than a painting does. Still, the book is not a wholly satisfactory scheme for putting groups of photographs into general circulation. The sequence in which the photographs are to be looked at is proposed by the order of pages, but nothing holds readers to the recommended order or indicates the amount of time to be spent on each photograph. Chris Marker's film, Si j'avais quatre dromadaires (1966), a brilliantly orchestrated meditation on photographs of all sorts and themes, suggests a subtler and more rigorous way of packaging (and enlarging) still photographs. Both the order and the exact time for looking at each photograph are imposed; and there is a gain in visual legibility and emotional impact. But photographs transcribed in a film cease to be collectible objects, as they still are when served up in books.

Photographs furnish evidence. Something we hear about, but doubt, seems proven when we're shown a photograph of it. In one version of its utility, the camera record incriminates. Starting with their use by the Paris police in the murderous roundup of Communards in June 1871, photographs became a useful tool of modern states in the surveillance and control of their increasingly mobile populations. In another version of its utility, the camera record justifies. A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what's in the picture. Whatever the limitations (through amateurism) or pretensions (through artistry) of the individual photographer, a photograph-any photograph-seems to have a more innocent, and therefore more accurate, relation to visible reality than do other mimetic objects. Virtuosi of the noble image like Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand, composing mighty, unforgettable photographs decade after decade, still want, first of all, to show something "out there," just like the Polaroid owner for whom photographs are a handy, fast form of note-taking, or the shutterbug with a Brownie who takes snapshots as souvenirs of daily life.

While a painting or a prose description can never be other than a narrowly selective interpretation, a photograph can be treated as a narrowly selective transparency. But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest, seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth. Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience. The immensely gifted members of the Farm Security Administration photographic project of the late 1930s (among them Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee) would take dozens of frontal pictures of one of their sharecropper subjects until satisfied that they had gotten just the right look on film-the precise expression on the subject's face that supported their own notions about poverty, light, dignity, texture, exploitation, and geometry. In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects. Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are. Those occasions when the taking of photographs is relatively undiscriminating, promiscuous, or self effacing do not lessen the didacticism of the whole enterprise. This very passivity-and ubiquity-of the photographic record is photography's "message," its aggression.

Images which idealize (like most fashion and animal photography) are no less aggressive than work which makes a virtue of plainness (like class pictures, still lifes of the bleaker sort, and mug shots). There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera. This is as evident in the 1840s and 1850s, photography's glorious first two decades, as in all the succeeding decades, during which technology made possible an ever increasing spread of that mentality which looks at the world as a set of potential photographs. Even for such early masters as David Octavius Hill and Julia Margaret Cameron who used the camera as a means of getting painterly images, the point of taking photographs was a vast departure from the aims of painters. From its start, photography implied the capture of the largest possible number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope. The subsequent industrialization of camera technology only carried out a promise inherent in photography from its very beginning: to democratize all experiences by translating them into images.

That age when taking photographs required a cumbersome and expensive contraption-the toy of 'the clever, the wealthy, and the obsessed-seems remote indeed from the era of sleek pocket cameras that invite anyone to take pictures. The first cameras, made in France and England in the early 1840s, had only inventors and buffs to operate them. Since there were then no professional photographers, there could not be amateurs either, and taking photographs had no clear social use; it was a gratuitous, that is, an artistic activity, though with few pretensions to being an art. It was only with its industrialization that photography came into its own as art. As industrialization provided social uses for the operations of the photographer, so the reaction against these uses reinforced the self-consciousness of photography-as-art.

“It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.”

Recently, photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing-which means that, like every mass art form, photography is not practiced by most people as an art. It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power.

Memorializing the achievements of individuals considered as members of families (as well as of other groups) is the earliest popular use of photography. For at least a century, the wedding photograph has been as much a part of the ceremony as the prescribed verbal formulas. Cameras go with family life. According to a sociological study done in France, most households have a camera, but a household with children is twice as likely to have at least one camera as a household in which there are no children. Not to take pictures of one's children, particularly when they are small, is a sign of parental indifference, just as not turning up for one's graduation picture is a gesture of adolescent rebellion.

Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself-a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness. It hardly matters what activities are photographed so long as photographs get taken and are cherished. Photography becomes a rite of family life just when, in the industrializing countries of Europe and America, the very institution of the family starts undergoing radical surgery. As that claustrophobic unit, the nuclear family, was being carved out of a much larger family aggregate, photography came along to memorialize, to restate symbolically, the imperiled continuity and vanishing extendedness of family life. Those ghostly traces, photographs, supply the token presence of the dispersed relatives. A family's photograph album is generally about the extended family-and, often, is all that remains of it.

As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism. For the first time in history, large numbers of people regularly travel out of their habitual environments for short periods of time. It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had. Photographs document sequences of consumption carried on outside the view of family, friends, neighbors. But dependence on the camera, as the device that makes real what one is experiencing, doesn't fade when people travel more. Taking photographs fills the same need for the cosmopolitans accumulating photograph-trophies of their boat trip up the Albert Nile or their fourteen days in China as it does for lower-middle-class vacationers taking snapshots of the Eiffel Tower or Niagara Falls.

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it-by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs. The very activity of taking pictures is soothing, and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel. Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture. This gives shape to experience: stop, take a photograph, and move on. The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic-Germans, Japanese, and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they can take pictures.

People robbed of their past seem to make the most fervent picture takers, at home and abroad. Everyone who lives in an industrialized society is obliged gradually to give up the past, but in certain countries, such as the United States and Japan, the break with the past has been particularly traumatic. In the early 1970s, the fable of the brash American tourist of the 1950s and 1960s, rich with dollars and Babbittry, was replaced by the mystery of the group minded tourist armed with two cameras, one on each hip.

Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation. One fullpage ad shows a small group of people standing pressed together, peering out of the photograph, all but one looking stunned, excited, upset. The one who wears a different expression holds a camera to his eye; he seems self-possessed, is almost smiling. While the others are passive, clearly alarmed spectators, having a camera has transformed one person into something active, a voyeur: only he has mastered the situation. What do these people see? We don't know. And it doesn't matter. It is an Event: something worth seeing-and therefore worth photographing. The ad copy, white letters across the dark lower third of the photograph like news coming over a teletype machine, consists of just six words: " ... Prague ... Woodstock ... Vietnam ... Sapporo ... Londonderry .. . LEICA." Crushed hopes, youth antics, colonial wars, and winter sports are alike-are equa lized by the camera. Taking photographs has set up a chronic voyeuristic relation to the world which levels the meaning of all events.

A photograph is not just the result of an encounter between an event and a photographer; picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights-to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on. Our very sense of situation is now articulated by the camera's interventions. The omnipresence of cameras persuasively suggests that time consists of interesting events, events worth photographing. This, in turn, makes it easy to feel that any event, once underway, and whatever its moral character, should be allowed to complete itselfso that something else can be brought into the world, the photograph. After the event has ended, the picture will still exist, conferring on the event a kind of immortality (and importance) it would never otherwise have enjoyed. While real people are out there killing themselves or other real people, the photographer stays behind his or her camera, creating a tiny element of another world: the image-world that bids to outlast us all.

Photographing is essentially an act of nonintervention. Part of the horror of such memorable coups of contemporary photojournalism as the pictures of a Vietnamese bonze reaching for the gasoline can, of a Bengali guerrilla in the act of ba yoneting a trussed-up collaborator, comes from the awareness of how plausible it has become, in situations where the photographer has the choice between a photograph and a life, to choose the photograph. The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene. Dziga Vertov's great film, Man with a Movie Camera (1'929), gives the ideal image of the photographer as someone in perpetual movement, someone movmg through a panorama of disparate events with such agility and speed that any intervention is out of the question. Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954) gives the complementary image: the photographer played by James Stewart has an intensified relation to one event, through his camera, precisely because he has a broken leg and is confined to a wheelchair; being temporarily immobilized prevents him from acting on what he sees, and makes it even more important to take pictures. Even if incompatible with intervention in a physical sense, using a camera is still a form of participation. Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing. Like sexual voyeurism, it is a way of at least tacitly, often explicitly, encouraging whatever is going on to keep on happening. To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged (at least for as long as it takes to get a "good" picture), to be in complicity with whatever makes a subject interesting, worth photographing-including, when that is the interest, another person's pain or misfortune.

Susan Sontag (1933 – 2004) was an American writer, critic, and intellectual, considered one of the most important and brilliant thinkers of her generation. Mostly writing in essay form, through she produced a number of novels and long form works, she explored ideas of art, culture, war, and pain with a singular voice and relentless insight.

Film

<div style="padding:57.51% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1091667411?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Simone Crawl 1970s"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - March 18, 2016

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - May 22, 2025

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1091667104?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Fred Hampton on the importance of revolutionary education"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Devil (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 7, 2025

The Devil is amongst the most feared cards in the tarot, he is the enemy of mankind. Each depiction shows a horned Devil alongside entrapped humans, but the cause of their entrapment varies greatly…

Name: The Devil

Number: XV

Astrology: Capricorn

Qabalah: Ayin, the Eye

Chris Gabriel June 7, 2025

The Devil is amongst the most feared cards in the tarot, he is the enemy of mankind. Each depiction shows a horned Devil alongside entrapped humans, but the cause of their entrapment varies greatly.

In Rider, we are given the most moral portrait. The Devil is in a traditional form - a man’s body with hairy goatlike legs and clawed feet. His goat horns are topped by a Pentagram, and they arch downwards to his bat wings. He holds his right hand up, while his left holds a flaming wand towards the ground. His face is bearded and monstrous. At his feet, a man and woman are chained to a column. They too are horned, nakeded, and tails protrude behind them. The woman has grown a tail tipped with a cluster of grapes, the man’s is tipped with flames.

In Thoth, the Devil is not a humanoid at all, but a goat replete with great spiralling horns, a third eye, and a bough of blue flowers. The stands in front of a great phallus crowned with a nimbus, and the entrapped souls are not chained, but are the sperm within the immense testes. They are not trapped in the way of the other two cards, rather, they are held in potentia, not yet actualized, but awaiting their future.

In Marseille, the Devil is the strangest of the three: a blue skinned beast with breasts and a penis. While the Rider Devil took on the pose of Baphomet, here we have the full hermaphroditic figure. The Devil differs greatly in different Marseille decks, often having a face in his stomach or eyes in his knees. His body is schizophrenically split into many organs and parts, each one conscious of itself, but the sum total of the Devil is unconscious as he uses his upheld flaming wand to light his way through the dark. The imps beside him have asinine ears and tails. Their horns are stick-like. They are chained to the pedestal of the Devil.

The Devil invites us into the depths of the Unconscious, the root of our desires and fear. This Hell is his home. Marseille and Rider clearly show that these wants are the sinful roots that sprout vice in our lives. The vices controlled by the Rider Devil are wrath, symbolized by the flaming tail, and drunkenness, symbolized by the grape tail. The Hell of this Devil is shown best in Disney’s Pinocchio as Pleasure Island, where ‘naughty boys’ go to smoke, drink and gamble, but soon are turned into asses, growing ears and tails, until they are enslaved and forced to work deep in the mines.

The vices of Marseille are bodily: lust, hunger, and the desires of the flesh. The Marseille Devil calls to mind the delusions of schizophrenics, as described by Victor Tausk, in which one's organs are felt to be foreign, and dominated by outside forces. This tends to be localized in the genitals, but can often spread throughout the whole body. The Devil is the embodiment of that eternal outsider who controls the bodies of the unwilling. As well described vividly by David Foster Wallace in Big Red Son, and typified by Origen, many will castrate themselves to overcome sin and grow closer to God.

Thoth shows us this is not necessary. The card shows the wisdom that Crowley received in the Book of the Law, that “the word of Sin is Restriction”, and that these unconscious forces need not fester down below, but demand to be expressed and brought forth into reality. The souls of the damned are not chained to the ground, but held as sperm awaiting their future fertilization.

Freud has shown that it is only when the drives are repressed, forced down into Hell, that they grow sick. As Blake writes in the Proverbs of Hell: He who desires, but acts not, breeds pestilence.

The Devil of Thoth is but an animal, and though he has a mystic third eye, he is driven by his sexual urges. He is the long maligned sexual drive at last given the freedom to create.

When the Devil comes up in a reading, we must be careful not to overindulge in our vices and follow our simple urges down, but instead to exalt, raise, and utilize them for greater creativity.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1091000142?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Personal Legacies- Materiality and Abstraction clip 6"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Pronoia Pt. 1 - The Art of Sacred Clowning

Molly Hankins June 5, 2025

Pronoia is paranoia’s positive counterpart and describes a worldview rooted in the idea that the universe is conspiring in our favor…

Molly Hankins June 5, 2025

Pronoia is paranoia’s positive counterpart and describes a worldview rooted in the idea that the universe is conspiring in our favor. Author Rob Brezney describes the concept in his 2005 book Pronoia, a modern-day, illustrated manual to life akin to Be Here Now by Ram Dass, and introduces two aspects of the sacred clown that can guide us towards pronoia. The first is a tummler, which is a Yiddish term that refers to someone who “makes a racket”, stirring up a commotion to heighten self-awareness. The second is the Iroquois word ondinnonk, meaning a secret wish of the soul that longs to do good deeds. Brezsny recommends that we allow our ondinnonk to lead our pronoaic mission as a tummler, so that we may elevate the consciousness of ourselves and our community.

Clowning is a primary expression of any tummler, whose sacred duty is to affectionately incite agitation that promotes self-reflection and positive action. The Native Amrican Hopi tribe ritualized the art of sacred clowning in an annual summer performance. Known as Kachina Ceremonies, these displays would last from the Winter to Summer Solstice with a six month build-up to the climax of the summer ritual, taking place in July because heat causes expansion drawing out impurities. Clowns, Princeton University Art and Archaeology Professor Hal Foster explained, played the essential role of clearing corruption out of the community by , “Tracing fractures that already exist in the given order to pressure them.” Existing areas of corruption were pressured to a breaking point by the affectionate agitation of the sacred clowns, and community members became strengthened by this release of impurities.

Brezsny believes that in order to see where corruption has accumulated within ourselves, our leaders and our communities, we must trigger each other. He writes in Pronoia, “We can inspire each other to perpetrate healing mischief, friendly shocks, compassionate tricks, blasphemous reverence, holy pranks and crazy wisdom.” This is the role of the sacred clown or tummler, guided by the good-natured principle of ondinnonk. Within a traditional social hierarchy, only the court jester can safely speak truth to power, and it can only be successfully communicated through play. The Hopi regarded corruption as an inevitability of being human, building in a social purification ceremony aligned with natural cycles to ensure that a corrupted people did not become the dominant force in the tribe.

In Pronoia, fundamentalism is the primary corruptive force of modernity, and Brezsny believes the fundamentalist attitude demands everything be taken too seriously, personally and literally. “Correct belief is the only virtue. Every fundamentalist is committed to waging war against the imagination unless the imagination is enslaved to his or her belief system,” he writes. “And here’s the bad news: like almost everyone in the world, each of us has our own share of the fundamentalist virus.” The next page of the book is blank except for an invitation to confess in writing where we harbor fundamentalism in our own worldviews, challenging us to realise how easy it is to see in others and ignore it in ourselves.

“Healing mischief, friendly shocks, compassionate tricks, blasphemous reverence, holy pranks and crazy wisdom”

If we endeavor to put pressure on the fractured places within our own psyche, we can uncover where fundamentalism has corrupted us and open ourselves up to otherwise unavailable opportunities. These are opportunities for both transcendent self-awareness and society-evolving consciousness expansion. Like the famous Leonard Cohen lyric from “Anthem” says, the cracks are where the light gets in. Though living by a pronaic philosophy in 2025 feels outlandish, it is radical to consider the possibility that we are currently experiencing an increase of pressure on existing fractures that will ultimately lead us to trade corruption for lightness. The fear of facing our own corrupted nature as individuals and a collective lightens when we approach it with a sense of humor.

Pronoia serves as an invitation to become tummlers unto ourselves, powered by the purity of our innate ondinnonk spirit that inherently wants to perpetuate goodness. As we do so, lightness spreads to the people around us and we all become more suited to administer the sort of, “...healing mischief, friendly shocks, compassionate tricks, blasphemous reverence, holy pranks and crazy wisdom,” that pressures the fractures of our own corruption and gives way to goodness.

Perhaps the secret of how to speed up this process in the collective lies in the blank page Breszny put in Pronoia. In the book’s forward he recommends we act as pronaic co-authors, knowing that the underlying axiom of “as above, so below” applies to both the macro and the microcosm. Breszny knows that to reflect upon and root out our own corruption is to become co-conspirators with the universe, scheming to generate more favor for ourselves and all of life. Embodying sacred clown energy as we undertake the process ensures success.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

Jack Clark

1h 58m

6.4.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Jack Clark about risk vs. reward.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/oc0ub0l4/widget?token=3b689ef67d066b68e976fa0bb2b036ee" frameborder="0"></iframe>