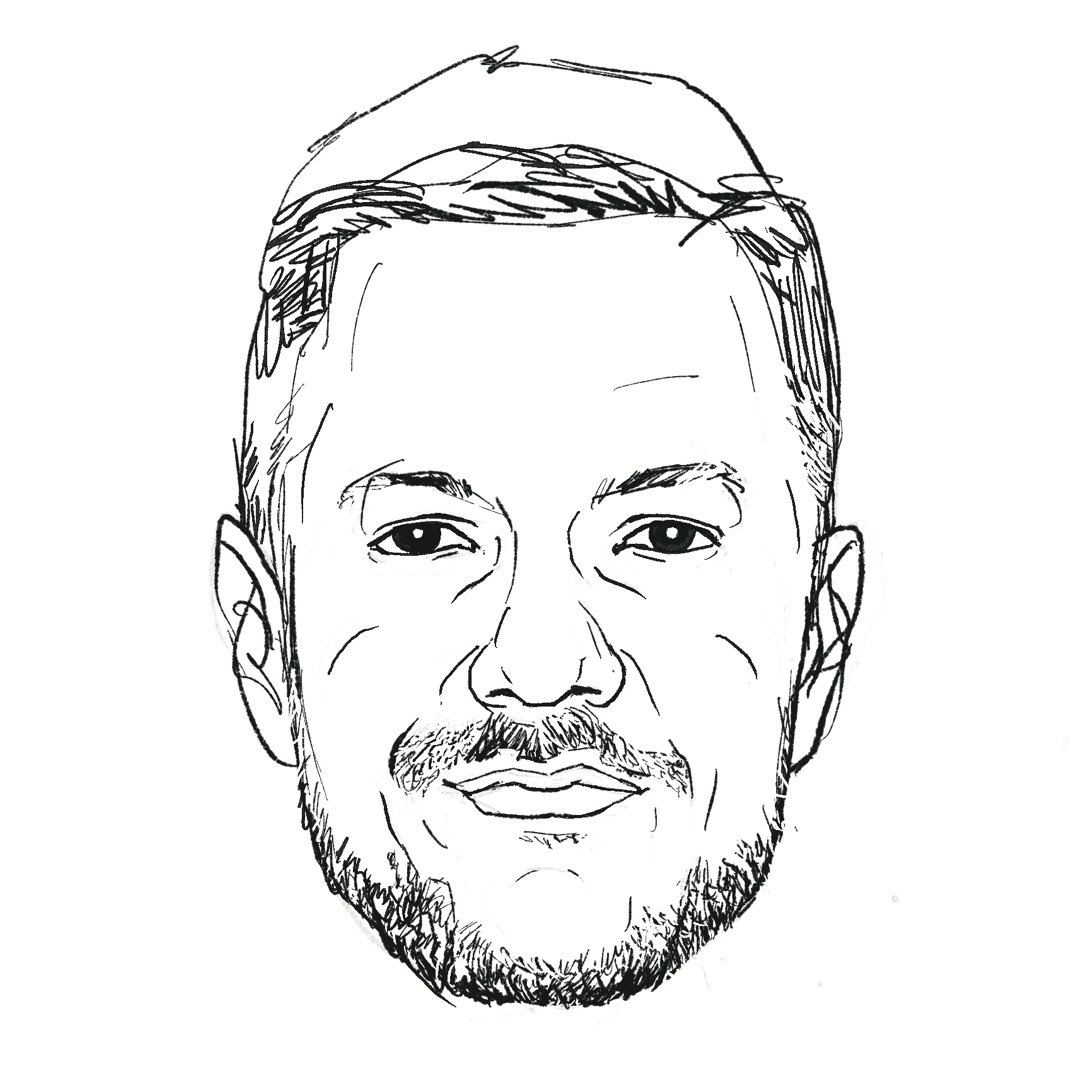

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - March 25, 2016

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - June 9, 2025

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1095507573?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Personal Legacies- Materiality and Abstraction clip 7"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Seven of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 21, 2025

The Seven of Disks is a card of waiting, of boredom, tedious labour, and perseverance. If the Six of Disks has given us a great gift of say a field or a house, this is the time where we “watch the grass grow” and the “paint dry”…

Name: Failure, Seven of Disks

Number: 7

Astrology: Saturn in Taurus

Qabalah: Netzach of He

Chris Gabriel June 21, 2025

The Seven of Disks is a card of waiting, of boredom, tedious labour, and perseverance. If the Six of Disks has given us a great gift of say a field or a house, this is the time where we “watch the grass grow” and the “paint dry”.

In Rider, we see a farmer leaning on his staff, looking sadly upon his growing crop. The sky is grey. He yearns for brilliant flourishing flowers, but must wait.

In Thoth, we have a more depressing image: dead plants covered in seven leaden coins. Four bear the face of Saturn, and three the Bull of Taurus. Saturn in Taurus is a long suffering placement, the efforts it undertakes can take years and years to come to fruition. This position requires constant effort without seeing results.

In Marseille, we have four coins about the corners of the card, with a central three forming an upright triangle. A flower grows from within the three. Qabalisitically, this is Netzach in He, the Beauty of the Princess.

“Rome was not built in a day” is an obvious, but painful truth. The materialization of our dreams and desires is not always a simple task. We wait in a dark night, knowing not when or if the Sun will rise, but we must keep going and have faith that it will pay off.

I am reminded of Churchill’s famous speech:

“We shall prove ourselves once more able to defend our island home, to ride out the storm of war, and to outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary for years, if necessary alone. At any rate, that is what we are going to try to do.”

This willingness to go on indefinitely is the dignified character of the Seven of Disks, the negative element is that of dejection and failure in the face of time.

Up to this point in the suit, each card has been focused on growing and developing the seeds of the future. This is perhaps the darkest point in the suit, when all of that hard work seems to be for nothing. This is not only the waiting for full growth, but the blight and pestilence which can affect what we have grown. Perhaps we have raised a large crop of wheat, only to find it blighted, overgrown with fungus. This is the sort of failure we face here.

When pulling this card, we must strengthen our resolve through any given setback, delay or difficulty. We must continue to have faith in a seemingly fruitless effort. The suit goes on to profit a great deal, this is just one difficult step toward a brilliant goal.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1095130138?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Kurt Vonnegut Shape of Stories"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

'Stalking The Wild Pendulum' Of Vibratory Attunement

Molly Hankins June 19, 2025

For many spiritual leaders, raising our vibration is synonymous with accessing higher levels of consciousness, but scientist and author Itzhak Bentov explains how this actually works in his book Stalking The Wild Pendulum…

Molly Hankins June 19, 2025

For many spiritual leaders, raising our vibration is synonymous with accessing higher levels of consciousness, but scientist and author Itzhak Bentov explains how this actually works in his book Stalking The Wild Pendulum. Bentov is a fascinating character - a Czech-born national named Tobias with no academic background who immigrated to British-controlled Palestine in the mid-1940s and became a mechanical engineer and inventor, changing his name after joining what would soon become the IDF Science Corp. His inventions range from rocket science components and medical devices to low-carb spaghetti, but his research into the mechanics of consciousness became his most memorable legacy.

Bentov believed that every living being has one material and one nonmaterial organizing system, and that no organized energy is ever lost. Just as our physical body is reabsorbed by the Earthly elements at the time of death, so too is our “organized energy body of information” reabsorbed by the organized information body of the cosmos. According to Bentov, these two systems produce a measurable frequency signal called the electro-static field, a vibration that can be measured by static meters. The strength of this signal depends on the vitality of the subject being measured; a person, plant or animal in poor physical health or depressed spirits will have a weaker signal than a healthy, happy subject. He claims stronger signals entrain vibrating bodies in their proximity. Entrainment occurs when two oscillating systems synchronize their rhythms, meaning a high-frequency electro-static field will raise the vibration of other beings in its field.

Meditative states entrain our physical bodies with the Earth’s vibration, strengthening and stabilizing the signal. As Maharishi Mahesh Yogi said, “If world peace is to be established, peace in the individual must be established first. Transcendental Meditation directly brings peace in the individual life.” Maharishi, who trained as a physicist, began teaching Transcendental Meditation in the 1950s and popularized it at a global scale after teaching The Beatles in the late 1960s. Stalking The Wild Pendulum provides a scientific basis for the idea that in order to bring peace to the world, we have to establish peace within ourselves first. Bentov’s work claims that when we become entrained with the Earth’s vibration, all of our vital functions become attuned to each other, synchronizing at seven cycles per second.

He gives another example of this phenomena using two grandfather clocks, each wound slightly differently so that the two swinging pendulums are out of sync. The faster moving pendulum, meaning the one with the higher frequency, will entrain the slower one, thereby increasing its speed and bringing the two resonance. In the first sentence of the book’s introduction, Bentov tells us that Stalking The Wild Pendulum is a product of late-night conversations with friends and colleagues calling future scientists to action. Instead of conclusively proving anything to the reader, his work invites us to apply the famous axiom of “as above so below” to draw our own conclusions from the parallels he points to between what he calls micro-realities, such as the behavior of two grandfather clock pendulums, and macro-realities, such as collective human behavior.

“We change reality as we change our level of consciousness”

Most of us have our own subjective experiences of interpersonal vibratory attunement. If we’re in a room with someone who is joyful, the mirror neurons in our brains make us feel joyful. The same applies to negative emotions. However, the logical conclusion from Bentov’s findings is that whoevers electrostatic signal is stronger and higher vibrating will ultimately raise the frequency of the other by being in their presence. Dr. David R. Hawkins created an emotional scale diagram showing specific electrostatic frequencies corresponding with different emotional states. Studies building on his work have since shown that shame has the lowest frequency and authenticity has the highest.

Our emotional states also correspond with what Bentov refers to as higher or lower consciousness. Higher consciousness, such as authenticity, has a wider range of possible responses to any given stimulus than lower consciousness, such as shame. He writes, “The higher we move along the scale of evolution, the higher the degree of free will, and the higher our ability to control or create our own environment.” It is not until our consciousness has expanded over different lives that we begin to build up our ability to exercise free will. As shared in the beginning of this essay, Bentov believed in both material and non-material organized systems of information energy, both of which evolve over time by way of experience.

By cultivating a stable, high-vibrating frequency via meditation, expanding our repertoire of personal experience, managing our emotional state and living authentically, we’re able to entrain others in our powerfully positive signal. This is the most important work that can be done on our planet now. Bentov said the terms “levels of consciousness” and “realities” were interchangeable - we change reality as we change our level of consciousness, and there is a critical mass element to this as Maharishi also claimed. The magic number, according to many yogic and spiritual traditions, is 144,000 people meditating enough to entrain their own signal with that of Earth, thereby entraining the signals of the rest of the global population.

Bentov goes a step further. He claims that when beings of higher consciousness focus their attention on beings of lower consciousness, the capabilities of lower consciousness-beings expand. Again, the level of consciousness refers only to how broad the range of possible responses are to any given stimulus - it’s not a value judgment. He writes, “As long as we are just sitting and producing idle thoughts, the thought energy is diffuse, and it eventually spreads out, weakens and disappears. However, when we consciously concentrate and send coherent thoughts, that thought energy or thought form will impinge on the person for whom the thought was meant.” Balancing our work between optimizing the health of our physical and non-physical organized information bodies will give us the energy to stabilize our signal and empower our thought forms to positively impact other beings.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

Film

<div style="padding:56.34% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1095506418?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Searchers clip 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Dan Reynolds

2h 7m

6.18.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Dan Reynolds about the juxtaposition of Las Vegas.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/1t0k33nc/widget?token=b132201ffcd874ce187ba2f29de79ff7" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094137561?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Greenwich Village Sunday clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Maeshowe, Sound, and Viking Runes (Artefact II)

Ben Timberlake June 17, 2025

Maeshowe is a Neolithic chambered burial complex on the Orkney Islands, an archipelago to the north of Scotland that is a floating world of midnight suns and brutal, dark winters. The tomb overlooks the Lochs of Harry and Stenness. On the narrow spit of land that separates the two lochs is The Ring of Brodgar, an ancient stone circle. It is nothing to look at from the outside - bored sheep munching salty grass on a small mound — but inside is one of the finest prehistoric monuments in the world…

WUNDERKAMMER #2

Artefact No: 2

Location: Maeshow, Orkney Islands, Scotland

Age: 5,000 years

Ben Timberlake June 17, 2025

Maeshowe is a Neolithic chambered burial complex on the Orkney Islands, an archipelago to the north of Scotland that is a floating world of midnight suns and brutal, dark winters. The tomb overlooks the Lochs of Harry and Stenness. On the narrow spit of land that separates the two lochs is The Ring of Brodgar, an ancient stone circle. It is nothing to look at from the outside - bored sheep munching salty grass on a small mound — but inside is one of the finest prehistoric monuments in the world.

The tomb’s structure is cruciform: a long passageway some 15m long, a central chamber, with three side-chambers. The main passageway is orientated to the southwest. Building began on the site around 2800BC. It is a work of monumental perfection: each wall of the long passageway is formed of single slabs up to three tons in weight; each corner of the main chamber has four vast standing stones; and the floors, walls and ceilings of the side-chambers are made from single stones. Smaller, long, thin slabs make up the rest of the masonry. They are fitted with unfussy but masterful precision in the local sandstone. It is even more impressive when you realize that these stones were cut and shaped thousands of years before the invention of metal tools. It is estimated to have taken 100,000 hours of labor to construct.

The interior chamber of Maeshowe, illuminated by the sun of the Winter Solstice.

Maeshowe sits within one of the richest prehistoric landscapes in Europe. The four principal sites are two stone circles - the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness - Maeshowe and the perfectly preserved Neolithic village of Skara Brae. These sites are within a further constellation of a dozen Neolithic and Bronze Age mounds, and other solitary standing stones.

Aligned within this landscape like a vast sundial, Maeshowe is sighted so as to tell the time just once a year, at midwinter. For a couple of weeks at either side of the winter solstice the sun sets to the southwest and the rays of the run enter down the long passage and illuminate the wall at the back of the end chamber. And this midwinter sun, at the zenith of its year, sets perfectly above the Barnhouse Stone some 700m away. The spectacle can be viewed live online every year.

Maeshowe and its sister sites are open to the public and well worth a visit. Because of their remote location they get a fraction of the visitor numbers similar sites receive. There is something deeply penitential about a visit there. The long passage is only a meter and a half tall and archaeologists believe it was designed this way to force people to bow and submit as they walked towards the center of the complex.

The Barnhouse Stone, on the left, aligns perfectly with the entrance to Maeshow, the mound on the right, so that on the day of midwinter, the sun sets above the stone and into the entrance to Maestowe.

“The frequency for Maeshowe was a drum being beaten at 2hz creating an infrasonic frequency that, although inaudible to us, could be felt as a physical or psychological sensations such as dizziness, raised heartbeat, and flying sensations. And that’s before we factor in the drugs.”

As much as Maeshowe is a place of the dead, it is also a temple to sound. Dr Aaron Watson, an honorary fellow from Exeter University, spent a number of years researching the effects of sound at different prehistoric sites. He found that specific pitches of vocal chants and different types of drumming could produce strange, amplified sound effects known as ‘standing waves’. These are very distinct areas of high and low intensity which seem to bear no relation to the source of the sound. In the case of Maeshowe, a drummer in the central chamber could be muted to those standing nearby but the sound would be vastly magnified in the side chambers. The acoustics are so powerful that the Neolithic builders must have known what they were doing when they built the structure. A recessed niche in one of the tunnel walls allowed a large stone to be dragged into the passageway blocking the passage and amplifying the sound.

Even more impressively was the possibility that Maeshowe displayed elements of the Helmholtz Effect - a phenomenon of air resonance in a cavity - but on a much larger scale. The frequency for Maeshowe was a drum being beaten at 2hz creating an infrasonic frequency that, although inaudible to us, could be felt as a physical or psychological sensations such as dizziness, raised heartbeat, and flying sensations. And that’s before we factor in the drugs. These European prehistoric societies made ample use of regular magic mushrooms and the red-and-white spotted Fly Agaric. To the Neolithic visitors the acoustics effects of Maeshowe alone must have been powerful but to combined with hallucinations it must have been one of the most profound and life changing experiences of their lives.

The tomb was rediscovered in 1861. I write ‘rediscovered’ because when the Victorian antiquarians began to clear soil and debris from the inner chambers, they came across evidence that they were not the first ones there since prehistoric times: the walls were adorned with Viking runes.

We have a very good idea who these Vikings were thanks to the Orkneyinga Saga, a medieval narrative history document woven through and embellished with myths. There appear to be two sets of culprits. Firstly, in 1151, a group of Viking Crusaders led by Earl Rognvald on their way to the Holy Land. Then, a couple years later - Christmas 1153 to be precise - a band of Viking looters on a raid led by Earl Harald.

The Norse traditionally held such ancient places with dread and it is not known what drove them to risk their mortal souls and enter the mound: a terrible storm is mentioned, but it may have been the legends of treasure too. The saga records that two of the Earl Rognvald’s men went mad with fear of the mythical Hogboon, from Old Norse hiagbui, or mound-dweller.

There are some 30 runes in Maeshowe, the largest collection outside Scandinavia. Here is a sample:

Crusaders broke into Maeshowe. Lif the earl's cook carved these runes. To the north-west is a great treasure hidden. It was long ago that a great treasure was hidden here. Happy is he that might find that great treasure.

Ofram, the son of Sigurd carved these runes.

Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes.

Thatir the weary Viking came here.

Ingigerth is the most beautiful of all women (carved beside a picture of a slavering dog).

Thorni fucked. Helgi carved.

All too often historians and archaeologists concern themselves with official inscriptions left by kings and emperors and other fevered egos but I don’t think that anything quite says ‘Look on my works ye mighty and despair’ than a Viking warrior getting laid and then recording it on the rock of ages with his axe.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094145452?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Soy Cuba clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Larry Levan Playlist

Archival 1987

Larry Levan was an influential American DJ who defined what modern dance clubs are today. He is most widely renowned for his long-time residency at Paradise Garage, also known as “Gay-Rage”, a former nightclub at 84 King Street in Manhattan, NY.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094123512?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Jack Kornfield clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Death (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 14, 2025

Death is undoubtedly the most feared card in the deck. He is a skeleton looking down at the bodies and souls of the dead below. While this card pertains to mortality itself, we shall see that death is far more than the failure of our bodies…

Name: Death or Nameless

Number: XIII

Astrology: Scorpio

Qabalah: Nun, a Fish

Chris Gabriel June 14, 2025

Death is undoubtedly the most feared card in the deck. He is a skeleton looking down at the bodies and souls of the dead below. While this card pertains to mortality itself, we shall see that death is far more than the failure of our bodies.

In Rider, Death is depicted Biblically, as the horseman on the pale steed.

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.

Revelation 6:8

The skeletal rider is clad in black armor with a red plume atop his helmet. He holds aloft a black flag emblazoned with a white rose, a symbol of purity. His horse is pale white with red eyes. Before him a bishop prays, a child kneels, his mother swoons, and a king lays dead, his crown fallen. Behind them is an island, a ship, and, on the horizon, the Sun, that sets between the two towers featured in the Moon.

In Thoth, Death is a black skeleton wearing the Atef crown of Osiris. He weaves the karmic tapestry of souls before him with his scythe. Above him is the phantom of an Eagle, below there is a serpent and a scorpion, all symbols of Scorpio, and a fish to symbolize Nun. This is the Grim Reaper.

In Marseille, we have a notably nameless card, the only one in the deck. Here Death is a skeletal Grim Reaper in a field of hands, feet, bones, and two decapitated heads. One is crowned, the other is shaggy.

A primary image that arises is that of the dead king, a symbol which Diogenes the Cynic expresses best. Alexander, having heard that Diogenes was the wisest man in the world, came to hear his wisdom. When he arrived, Diogenes was digging through the waste of his trash can home. Alexander asked him what he was doing, to which he replied “I am trying to distinguish the bones of your father from those of a slave.”

As Shakespeare says, “Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots. Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service—two dishes, but to one table. That’s the end.”

Death is the great equalizer: beneath masks and costumes, beautiful and ugly flesh, lays a pale skeleton. The skull is a profound truth, and death’s head has always been used to terrify. Nearly every ancient culture revered it, pirates raised it as their flag, even today American police officers wear it on their uniforms.

Death in occultism, however, is more akin to the death of Paul, who says “I die daily”. The Scorpion willingly kills itself when surrounded by flames. This card invites us to “Die”, transform our body through terrifying alchemical processes and, like the white flower, be made purer. Our essence is distilled through this continual cycle of life and death. The given number of 13, an unlucky number, signifies this very thing. After the 12 hours, the 12 months, the 12 signs of the Zodiac, what comes next? What comes after the end?

When we pull this card, we must not be afraid. Instead, willingly put an end to what is limiting you,nand to the stilted, decaying structures that you cling to. People spend their whole lives avoiding change and, in doing so, die long before their body. When we decide to shed our skin like the serpent, we can have absolute confidence that we are becoming a stronger, greater version of ourselves.

When we outgrow our old life, we must die and be born again.

Film

<div style="padding:53.33% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1094132387?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Playtime clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

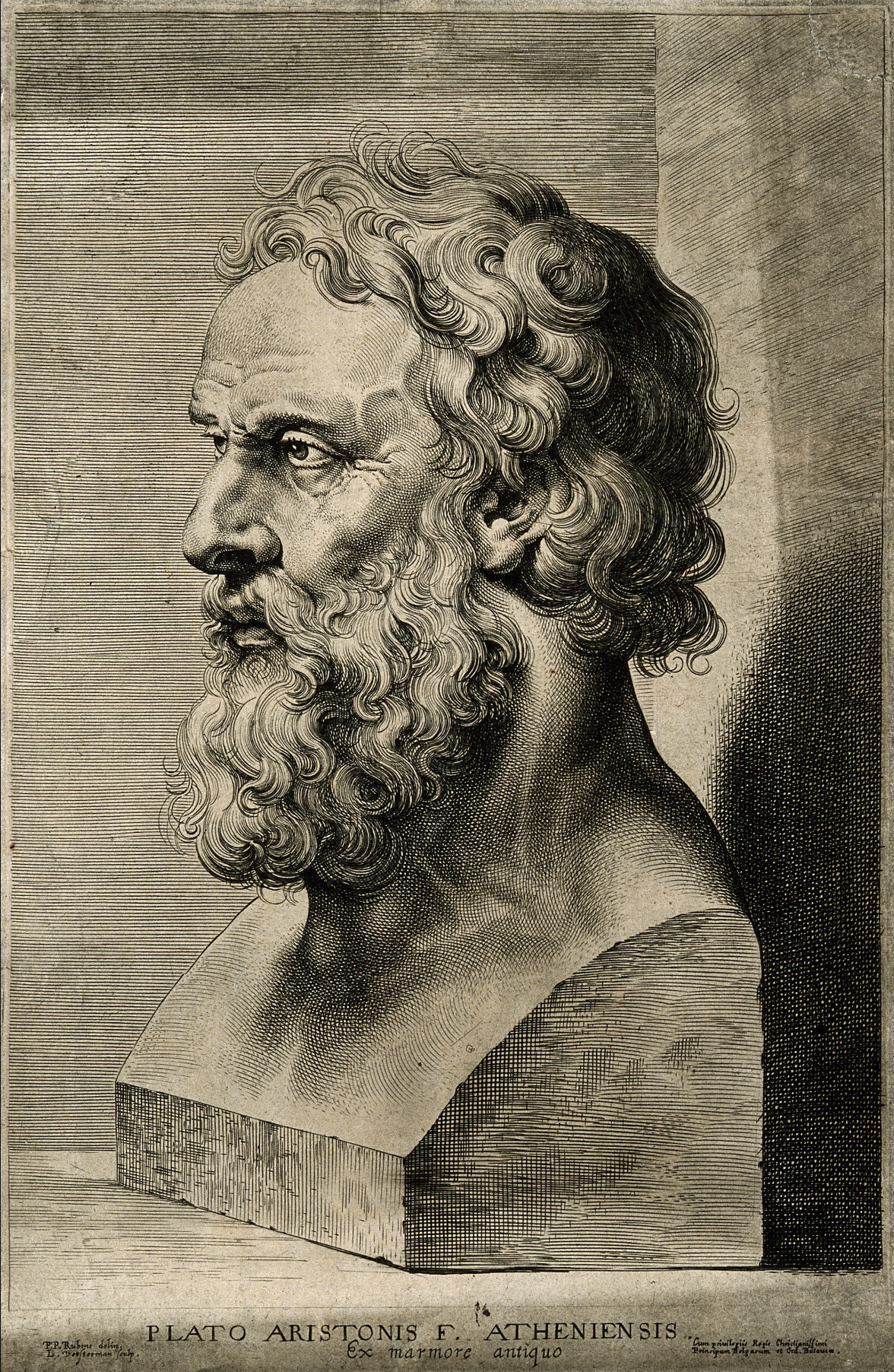

Footnotes to Plato (c.428-347BC)

Nicko Mroczkowski June 11, 2025

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name…

Rafael's School of Athens, 1511.

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name.

In this flourishing new culture, thinkers began to try and understand the world in a more organised way. From this, Western philosophy was born, and science came along with it. These thinkers asked themselves: what is the world made of, and how does it work? This was not a new question, most likely every culture before had asked it in some way, but what made the Ancient Greeks unique was their systematic approach. Because they also asked a secondary question, which, arguably, is still the starting point of any scientific inquiry: what is the correct way to talk about what something is?

L. Vosterman, after Rubens. c. 1620.

Each of the very first philosophers answered this question with one thing: ‘substance’, or stuff. They believed that the right way to understand the world is in terms of a single type of matter, which is present in different proportions in everything that exists. Thales of Miletus, perhaps the earliest Greek philosopher, believed that all things come from water; solid matter, life, and heat are all special phases of the same liquid. For him, then, the true way to talk about an apple, for example, is as a particularly dense piece of moisture. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything is made of fire; all existence is in flux, like the dancing flame, of which an apple is a fleeting shape.

We don’t know much more about these thinkers, as not much of their work survives; most of the accounts we have are second hand. We only know for sure that each proposed a different ultimate substance that everything is made out of. Then, a little while later, along came a philosopher called Plato.

Despite its prominence, ‘Plato’ was actually a nickname meaning ‘broad’ – there is disagreement about its origin, but the most popular theory is that it comes from his time as a wrestler. His real name is thought to have been ‘Aristocles’. Whatever he was really called, Plato changed everything. Instead of arguing, like his predecessors, for a different kind of ultimate substance, he observed that substance alone is not enough to explain what exists: there is also form. In other words, he more or less invented the distinction between form and content.

One could spend a lifetime analysing these terms, and there are whole volumes of art and literary theory that address their nuances; but it’s also a common-sense distinction that we use every day. The form of something is its shape, structure, composition; the content, or substance, is the stuff it’s made of. So the form of an apple is a sweet fruit with a specific genetic profile, and its content is various hydrocarbons and trace elements. The form of a literary work is its style and composition – poetry or prose, past or present tense, first- or third-person, etc. – and its content is its subject matter, what it describes and what happens in it.

An attempt at a classification of the perfect form of a rabbit. (1915)

We can already see Plato’s influence on modern knowledge in these examples. The correct way to talk about something, for him, was primarily in terms of its form, and only secondarily in terms of its substance. This is still the case for us today. There is a powerful justification for this preference: it allows us to talk about things generally. This is basically the foundation of any science; we would get absolutely nowhere if we only analysed particular individuals. There are just too many things out there. No two animals of the same species, for example, will ever have exactly the same make-up – even if they’re clones. They have eaten different things, had different experiences; they also, quite frankly, create and shed cells so rapidly and unpredictably that differences in their substance are inevitable. What they do have in common, though, is their anatomy, behaviour, and an overall genetic profile that produces these things.

Forms are peculiar, however, because they don’t exist in the same way as substances do. While there are concrete definitions of substances, the same cannot be said for forms. There are, for example, no perfect triangles in existence, and we could probably never create one – zoom in enough, and something will always be slightly out of place. So how did Plato come up with the idea of something that can never be experienced in real life? The answer is precisely because of things like triangles. Mathematics, and especially geometry, is the original language of forms, and it can describe a perfect triangle or circle, even though one may never exist. The success of mathematical inquiries in Plato’s time allowed him to recognise that the concept of forms which worked in geometry can be applied to understand the world more generally.

Forms are perfect specimens of imperfect things, are exemplars, or things we aspire to – they are the way things ought to be, in a perfect world. ‘Form’ in Plato’s work is also sometimes translated as ‘idea’ or ‘ideal’. And so, Plato’s answer to the question of how to conduct scientific inquiry was this: the correct way to talk about something is in terms of how it should be. Despite our imperfect world, rational thinking – the capacity of the human mind for grasping things like mathematical truths – can do this, and that’s what sets human beings and their societies apart from the rest of nature.

Perfect Platonic Solids

It gets a little strange from this point on: Plato believes that forms really exist, but in a separate, perfect world. Our souls start out there and then make their way to the material world to be born, but still have implicit knowledge of their original home, and this is where reason originates. Improbable, yes, but not completely absurd. Plato was clearly trying to explain, to a society that was just beginning to understand the importance of perfect knowledge, how it could exist in our imperfect world of change and difference. Two millennia later, Kant would show that it’s due to the way the human mind is structured, but we don’t really know how this happened either.

Really, we’re still playing Plato’s game. The basic realisation that to know the world, we must study the general and the perfect, and ignore the non-essential characteristics of particular individuals – this is his legacy. Of course, this way of thinking is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it can be hard to grapple with; it’s so fundamental that we take it for granted. But what we call knowledge today would not be possible at all without it. Seeing this, we can imagine what the influential British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead meant when he wrote that ‘the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Nicko Mroczkowski

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1092213848?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Acting Shakespeare- The Two Traditions clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

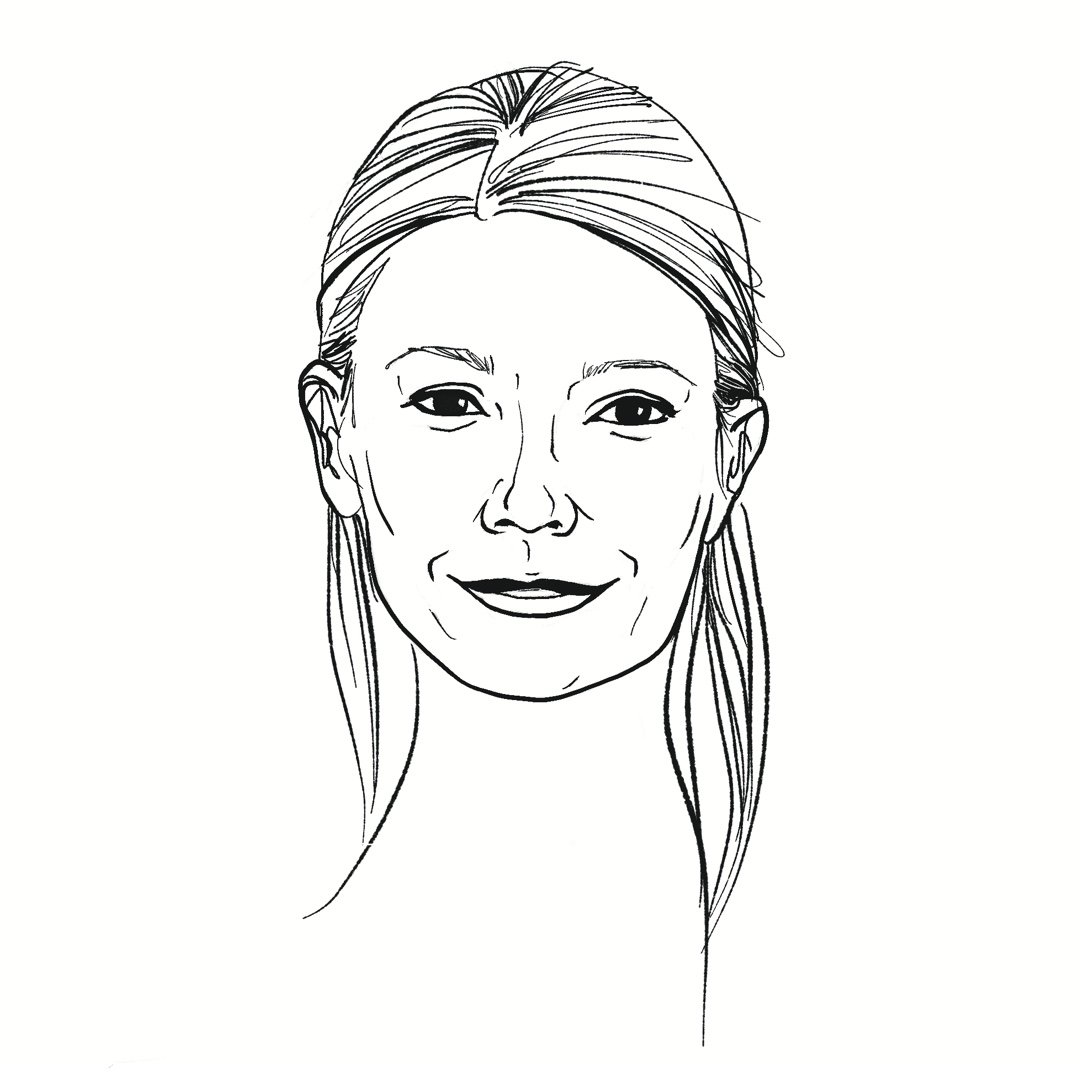

Gwyneth Paltrow

1h 24m

6.11.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Gwyneth Paltrow about adhering to social expectations.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/3rouuii2/widget?token=ac059634f4da574e8bfdbd9b30cdfd90" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1092236340?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Portrait of Jennie clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

On Photography (Excerpt)

Susan Sontag June 10, 2025

To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store…

Portraits in Life and Death, Peter Hujar. 1976.

When Susan Sontag released ‘On Photography’ in 1977, itself a collection of essays written in the preceding four years, it announced a new era in thinking about the medium. In the near fifty years since, it has become easy to overlook how radical Sontag’s ideas were for they have been absorbed so readily into the common theoretical understanding of photography we struggle to understand photography outside of her thinking. The book considers photography as a somewhat violent act that fosters a voyeuristic relationship with the world, separate from the reality it purports to capture. Yet the work is not inherently critical of the medium, instead it asks us to consider the power of depiction that the camera gives us, and to weild the tool with respect and compassion.

Susan Sontag June 10, 2025

To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store. In Godard's Les Carabiniers (1963), two sluggish lumpen-peasants are lured into joining the King's Army by the promise that they will be able to loot, rape, kill, or do whatever else they please to the enemy, and get rich. But the suitcase of booty that Michel-Ange and Ulysse triumphantly bring home, years later, to their wives turns out to contain only picture postcards, hundreds of them, of Monuments, Department Stores, Mammals, Wonders of Nature, Methods of Transport, Works of Art, and other classified treasures from around the globe. Godard's gag vividly parodies the equivocal magic of the photographic image. Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognize as modern. Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.

To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge-and, therefore, like power. A now notorious first fall into alienation, habituating people to abstract the world into printed words, is supposed to have engendered that surplus of Faustian energy and psychic damage needed to build modern, inorganic societies. But print seems a less treacherous form of leaching out the world, of turning it into a mental object, than photographic images, which now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the present. What is written about a person or an event is frankly an interpretation, as are handmade visual statements, like paintings and drawings. Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.

Photographs, which fiddle with the scale of the world, themselves get reduced, blown up, cropped, retouched, doctored, tricked out. They age, plagued by the usual ills of paper objects; they disappear; they become valuable, and get bought and sold; they are reproduced. Photographs, which package the world, seem to invite packaging. They are stuck in albums, framed and set on tables, tacked on walls, projected as slides. Newspapers and magazines feature them; cops alphabetize them; museums exhibit them; publishers compile them.

For many decades the book has been the most influential way of arranging (and usually miniaturizing) photographs, thereby guaranteeing them longevity, if not immortality-photographs are fragile objects, easily torn or mislaid-and a wider public. The photograph in a book is, obviously, the image of an image. But since it is, to begin with, a printed, smooth object, a photograph loses much less of its essential quality when reproduced in a book than a painting does. Still, the book is not a wholly satisfactory scheme for putting groups of photographs into general circulation. The sequence in which the photographs are to be looked at is proposed by the order of pages, but nothing holds readers to the recommended order or indicates the amount of time to be spent on each photograph. Chris Marker's film, Si j'avais quatre dromadaires (1966), a brilliantly orchestrated meditation on photographs of all sorts and themes, suggests a subtler and more rigorous way of packaging (and enlarging) still photographs. Both the order and the exact time for looking at each photograph are imposed; and there is a gain in visual legibility and emotional impact. But photographs transcribed in a film cease to be collectible objects, as they still are when served up in books.

Photographs furnish evidence. Something we hear about, but doubt, seems proven when we're shown a photograph of it. In one version of its utility, the camera record incriminates. Starting with their use by the Paris police in the murderous roundup of Communards in June 1871, photographs became a useful tool of modern states in the surveillance and control of their increasingly mobile populations. In another version of its utility, the camera record justifies. A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what's in the picture. Whatever the limitations (through amateurism) or pretensions (through artistry) of the individual photographer, a photograph-any photograph-seems to have a more innocent, and therefore more accurate, relation to visible reality than do other mimetic objects. Virtuosi of the noble image like Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand, composing mighty, unforgettable photographs decade after decade, still want, first of all, to show something "out there," just like the Polaroid owner for whom photographs are a handy, fast form of note-taking, or the shutterbug with a Brownie who takes snapshots as souvenirs of daily life.

While a painting or a prose description can never be other than a narrowly selective interpretation, a photograph can be treated as a narrowly selective transparency. But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest, seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth. Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience. The immensely gifted members of the Farm Security Administration photographic project of the late 1930s (among them Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee) would take dozens of frontal pictures of one of their sharecropper subjects until satisfied that they had gotten just the right look on film-the precise expression on the subject's face that supported their own notions about poverty, light, dignity, texture, exploitation, and geometry. In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects. Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are. Those occasions when the taking of photographs is relatively undiscriminating, promiscuous, or self effacing do not lessen the didacticism of the whole enterprise. This very passivity-and ubiquity-of the photographic record is photography's "message," its aggression.

Images which idealize (like most fashion and animal photography) are no less aggressive than work which makes a virtue of plainness (like class pictures, still lifes of the bleaker sort, and mug shots). There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera. This is as evident in the 1840s and 1850s, photography's glorious first two decades, as in all the succeeding decades, during which technology made possible an ever increasing spread of that mentality which looks at the world as a set of potential photographs. Even for such early masters as David Octavius Hill and Julia Margaret Cameron who used the camera as a means of getting painterly images, the point of taking photographs was a vast departure from the aims of painters. From its start, photography implied the capture of the largest possible number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope. The subsequent industrialization of camera technology only carried out a promise inherent in photography from its very beginning: to democratize all experiences by translating them into images.

That age when taking photographs required a cumbersome and expensive contraption-the toy of 'the clever, the wealthy, and the obsessed-seems remote indeed from the era of sleek pocket cameras that invite anyone to take pictures. The first cameras, made in France and England in the early 1840s, had only inventors and buffs to operate them. Since there were then no professional photographers, there could not be amateurs either, and taking photographs had no clear social use; it was a gratuitous, that is, an artistic activity, though with few pretensions to being an art. It was only with its industrialization that photography came into its own as art. As industrialization provided social uses for the operations of the photographer, so the reaction against these uses reinforced the self-consciousness of photography-as-art.

“It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.”

Recently, photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing-which means that, like every mass art form, photography is not practiced by most people as an art. It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power.

Memorializing the achievements of individuals considered as members of families (as well as of other groups) is the earliest popular use of photography. For at least a century, the wedding photograph has been as much a part of the ceremony as the prescribed verbal formulas. Cameras go with family life. According to a sociological study done in France, most households have a camera, but a household with children is twice as likely to have at least one camera as a household in which there are no children. Not to take pictures of one's children, particularly when they are small, is a sign of parental indifference, just as not turning up for one's graduation picture is a gesture of adolescent rebellion.

Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself-a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness. It hardly matters what activities are photographed so long as photographs get taken and are cherished. Photography becomes a rite of family life just when, in the industrializing countries of Europe and America, the very institution of the family starts undergoing radical surgery. As that claustrophobic unit, the nuclear family, was being carved out of a much larger family aggregate, photography came along to memorialize, to restate symbolically, the imperiled continuity and vanishing extendedness of family life. Those ghostly traces, photographs, supply the token presence of the dispersed relatives. A family's photograph album is generally about the extended family-and, often, is all that remains of it.

As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism. For the first time in history, large numbers of people regularly travel out of their habitual environments for short periods of time. It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had. Photographs document sequences of consumption carried on outside the view of family, friends, neighbors. But dependence on the camera, as the device that makes real what one is experiencing, doesn't fade when people travel more. Taking photographs fills the same need for the cosmopolitans accumulating photograph-trophies of their boat trip up the Albert Nile or their fourteen days in China as it does for lower-middle-class vacationers taking snapshots of the Eiffel Tower or Niagara Falls.

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it-by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs. The very activity of taking pictures is soothing, and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel. Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture. This gives shape to experience: stop, take a photograph, and move on. The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic-Germans, Japanese, and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they can take pictures.

People robbed of their past seem to make the most fervent picture takers, at home and abroad. Everyone who lives in an industrialized society is obliged gradually to give up the past, but in certain countries, such as the United States and Japan, the break with the past has been particularly traumatic. In the early 1970s, the fable of the brash American tourist of the 1950s and 1960s, rich with dollars and Babbittry, was replaced by the mystery of the group minded tourist armed with two cameras, one on each hip.

Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation. One fullpage ad shows a small group of people standing pressed together, peering out of the photograph, all but one looking stunned, excited, upset. The one who wears a different expression holds a camera to his eye; he seems self-possessed, is almost smiling. While the others are passive, clearly alarmed spectators, having a camera has transformed one person into something active, a voyeur: only he has mastered the situation. What do these people see? We don't know. And it doesn't matter. It is an Event: something worth seeing-and therefore worth photographing. The ad copy, white letters across the dark lower third of the photograph like news coming over a teletype machine, consists of just six words: " ... Prague ... Woodstock ... Vietnam ... Sapporo ... Londonderry .. . LEICA." Crushed hopes, youth antics, colonial wars, and winter sports are alike-are equa lized by the camera. Taking photographs has set up a chronic voyeuristic relation to the world which levels the meaning of all events.

A photograph is not just the result of an encounter between an event and a photographer; picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights-to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on. Our very sense of situation is now articulated by the camera's interventions. The omnipresence of cameras persuasively suggests that time consists of interesting events, events worth photographing. This, in turn, makes it easy to feel that any event, once underway, and whatever its moral character, should be allowed to complete itselfso that something else can be brought into the world, the photograph. After the event has ended, the picture will still exist, conferring on the event a kind of immortality (and importance) it would never otherwise have enjoyed. While real people are out there killing themselves or other real people, the photographer stays behind his or her camera, creating a tiny element of another world: the image-world that bids to outlast us all.

Photographing is essentially an act of nonintervention. Part of the horror of such memorable coups of contemporary photojournalism as the pictures of a Vietnamese bonze reaching for the gasoline can, of a Bengali guerrilla in the act of ba yoneting a trussed-up collaborator, comes from the awareness of how plausible it has become, in situations where the photographer has the choice between a photograph and a life, to choose the photograph. The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene. Dziga Vertov's great film, Man with a Movie Camera (1'929), gives the ideal image of the photographer as someone in perpetual movement, someone movmg through a panorama of disparate events with such agility and speed that any intervention is out of the question. Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954) gives the complementary image: the photographer played by James Stewart has an intensified relation to one event, through his camera, precisely because he has a broken leg and is confined to a wheelchair; being temporarily immobilized prevents him from acting on what he sees, and makes it even more important to take pictures. Even if incompatible with intervention in a physical sense, using a camera is still a form of participation. Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing. Like sexual voyeurism, it is a way of at least tacitly, often explicitly, encouraging whatever is going on to keep on happening. To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged (at least for as long as it takes to get a "good" picture), to be in complicity with whatever makes a subject interesting, worth photographing-including, when that is the interest, another person's pain or misfortune.

Susan Sontag (1933 – 2004) was an American writer, critic, and intellectual, considered one of the most important and brilliant thinkers of her generation. Mostly writing in essay form, through she produced a number of novels and long form works, she explored ideas of art, culture, war, and pain with a singular voice and relentless insight.