Film

<div style="padding:55.78% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1105722413?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="North by Northwest clip 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - January 12, 2025

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1104866427?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Cover Girl clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

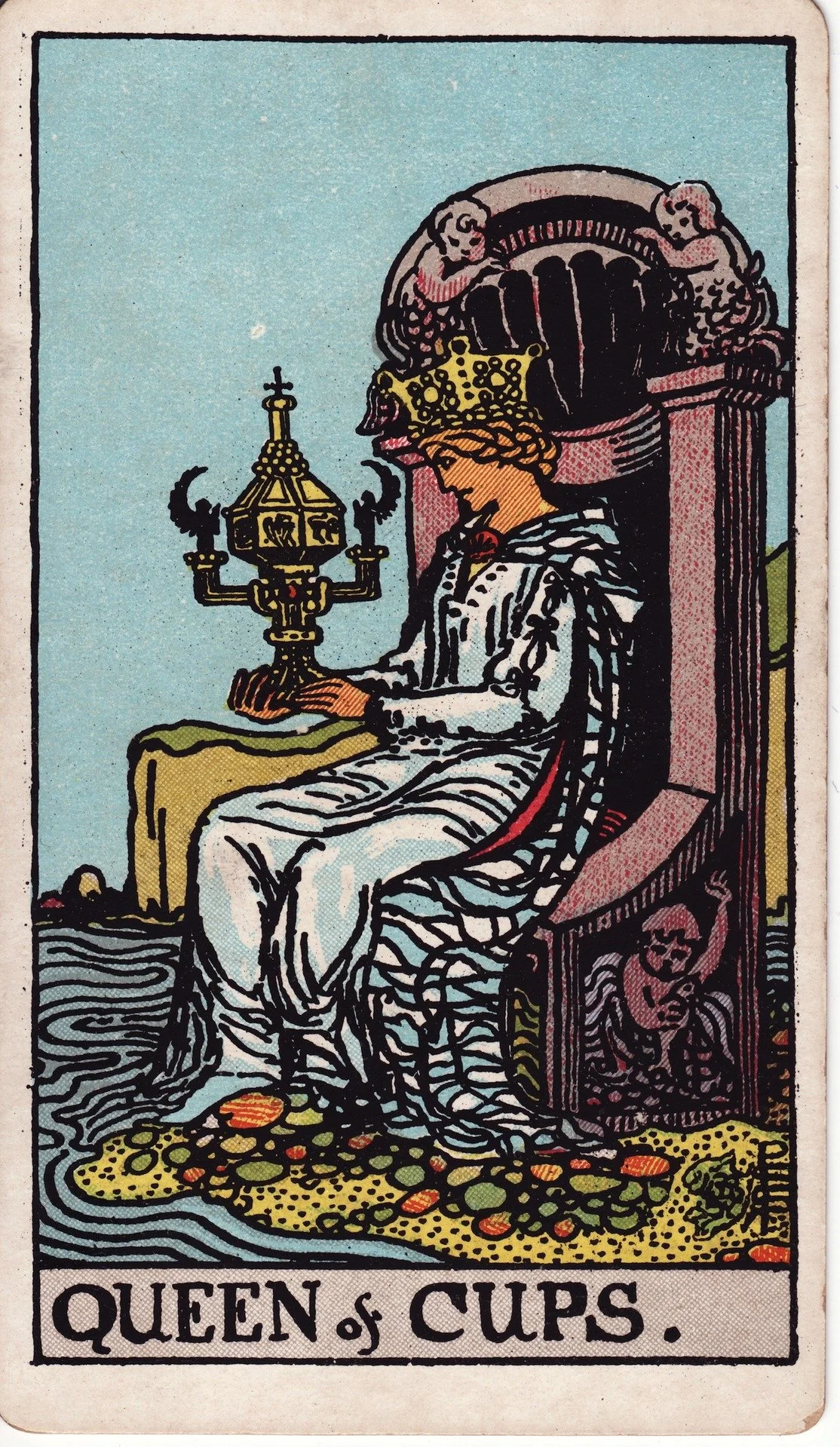

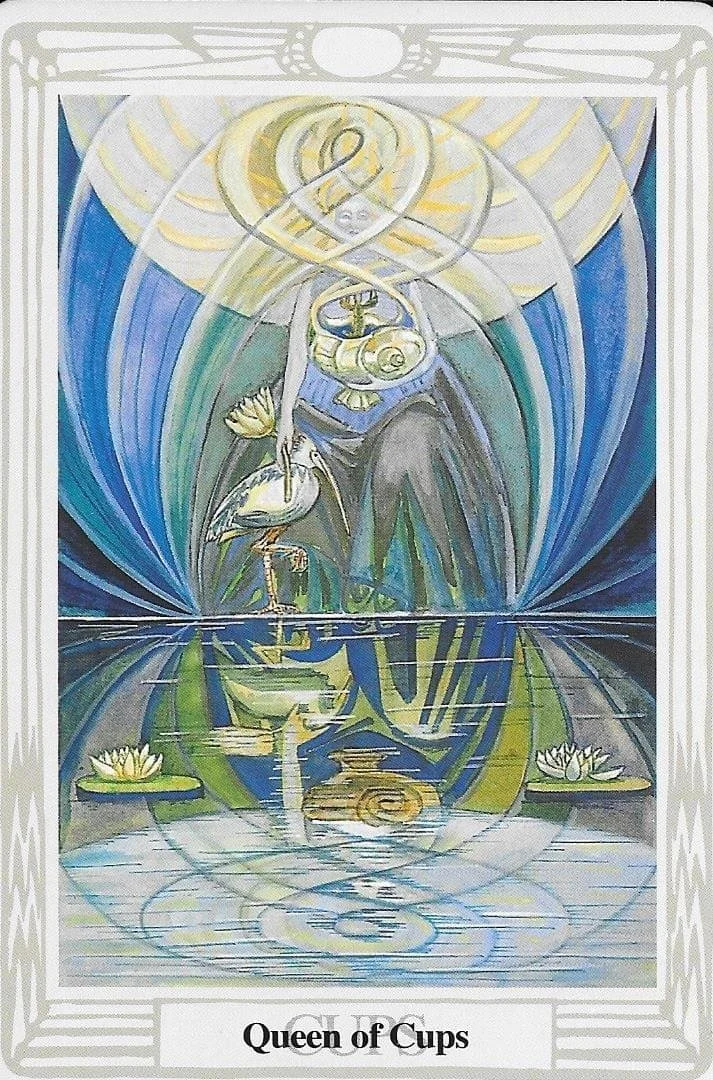

Queen of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 26, 2025

The Queen of Cups is the wateriest card in the deck and the quintessence of the element. She is the Mother enthroned, holding her precious womblike grail. She is both guarded and receptive…

Name: Queen of Cups

Number: 2

Astrology: Cancer, Water of Water

Qabalah: He of He

Chris Gabriel July 26, 2025

The Queen of Cups is the wateriest card in the deck and the quintessence of the element. She is the Mother enthroned, holding her precious womblike grail. She is both guarded and receptive.

In Rider, we have a blonde Queen in a diaphanous gown that melds with the water at her feet. Her throne is adorned by cherubs and shells, and set upon a stony beach. The Cup she holds is closed and complex in its design. Like the Ark of the Covenant it is sealed and guarded by angels. It is topped by a cross and she looks intensely at it.

In Thoth, the Queen is barely visible; her skin is blue, and her face is obscured by the water which flows about her. She holds a lotus in one hand, and in the other, a large shelllike cup from which a little crustaceans peeks out. She is petting an Ibis. The pool she stands in has two lotuses.

In Marseille, the Queen is blonde, she looks upon her sealed cup and holds a wavy dagger, ready to defend what is hers.

As the Queen of Cups is given to Cancer, we see the contradictory nature of the card: a cup is meant to be open, to receive water and wine, but the crab of the zodiac is armored and defensive, so her cup is closed off.

She is protecting what is hers. The Mother who is fiercely protective of her children, or in a negative aspect, a smothering, over protective, and controlling matriarch. She is a lover who sits ready with her dagger to ward off those who would enter her heart or womb.

An image that arises in Thoth is that of the woman who “loses herself” in love, whether romantic or maternal. Her identity and individuality is secondary to her role. These are universal problems: how do we exist as individuals when surrounded by others? When does defensiveness veer into alienation? How do we let the right people in and keep the wrong people out?

These are the same issues that concern the Chariot, though on a smaller scale. He protects the nation, but the Queen of Cups, another form of Cancer, protects herself and her family. These are the same energies operating on different wavelengths.

Each Queen depicted seems to have a different solution. Rider holds her Cup tightly with both hands - she keeps it sealed, and under constant surveillance. Marseille holds it with one hand, but is ready with a dagger in the other to keep it safe. Thoth hides and disguises herself, she keeps it open, but with a guardian.

Each solution comes with its own problem, but they all lead the queen to become a “homebody”, a crab happy to live in the same pool forever. Their attention is fixed so strongly upon what is theirs and how to keep it safe that they fail to explore. This is clear when we compare with the opposite card, the Capricornian Queen of Disks, who wants to rise and gain greater power over more space.

When we pull this card, we may be called on to protect what is ours, to mother and care for someone. It may also directly indicate a Cancer that we know.

Film

<div style="padding:72.58% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1104054581?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Singin' in the Rain clip 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Sea and the Wind That Blows

E.B. White July 24, 2025

Waking or sleeping, I dream of boats - usually of rather small boats under a slight press of sail. When I think how great a part of my life has been spent dreaming the hours away and how much of this total dream life has concerned small craft, I wonder about the state of my health, for I am told that it is not a good sign to be always voyaging into unreality, driven by imaginary breezes…

Sailing a Dory, Winslow Homer. 1880.

A meditation on ageing and an elegy for passion, as E.B. White approached his twilight years in 1963 he looked back on his defining love in this piece first published in ‘Ford Times’. What begins as a dream of boats becomes a study of memory, solitude, and the strange pull of the water. Written as a way to say goodbye as he retire from his hobby, White questions whether he can even leave behind that which seems to define him - his strange, lifelong entanglement with the sea.

E. B. White July 24, 2025

Waking or sleeping, I dream of boats - usually of rather small boats under a slight press of sail. When I think how great a part of my life has been spent dreaming the hours away and how much of this total dream life has concerned small craft, I wonder about the state of my health, for I am told that it is not a good sign to be always voyaging into unreality, driven by imaginary breezes.

I have noticed that most men, when they enter a barber shop and must wait their turn, drop into a chair and pick up a magazine. I simply sit down and pick up the thread of my sea wandering, which began more than fifty years ago and is not quite ended. There is hardly a waiting room in the East that has not served as my cockpit, whether I was waiting to board a train or to see a dentist. And I am usually still trimming sheets when the train starts or the drill begins to whine. If a man must be obsessed by something, I suppose a boat is as good as anything, perhaps a bit better than most. A small sailing craft is not only beautiful, it is seductive and full of strange promise and the hint of trouble. If it happens to be an auxiliary cruising boat, it is without question the most compact and ingenious arrangement for living ever devised by the restless mind of man - a home that is stable without being stationary, shaped less like a box than like a fish or a bird or a girl, and in which the homeowner can remove his daily affairs as far from shore as he has the nerve to take them, close-hauled or running free -parlor, bedroom, and bath, suspended and alive.

Men who ache allover for tidiness and compactness in their lives often find relief for their pain in the cabin of a thirty-foot sailboat at anchor in a sheltered cove. Here the sprawling panoply of The Home is compressed in orderly miniature and liquid delirium, suspended between the bottom of the sea and the top of the sky, ready to move on in the morning by the miracle of canvas and the witchcraft of rope. It is small wonder that men hold boats in the secret place of their mind, almost from the cradle to the grave.

Along with my dream of boats has gone the ownership of boats, a long succession of them upon the surface of the sea, many of them makeshift and crank.

Since childhood I have managed to have some sort of sailing craft and to raise a sail in fear. Now, in my sixties, I still own a boat, still raise my sail in fear in answer to the summons of the unforgiving sea.

Why does the sea attract me in the way it does: Whence comes this compulsion to hoist a sail, actually or in dream? My first encounter with the sea was a case of hate at first sight. I was taken, at the age of four, to a bathing beach in New Rochelle. Everything about the experience frightened and repelled me: the taste of salt in my mouth, the foul chill of the wooden bathhouse, the littered sand, the stench of the tide flats. I came away hating and fearing the sea. Later, I found that what I had feared and hated, I now feared and loved.

I returned to the sea of necessity, because it would support a boat; and although I knew little of boats, I could not get them out of my thoughts. I became a pelagic boy. The sea became my unspoken challenge: the wind, the tide, the fog, the ledge, the bell, the gull that cried help, the never-ending threat and bluff of weather.

Once having permitted the wind to enter the belly of my sail, I was not able to quit the helm; it was as though I had seized hold of a high-tension wire and could not let go.

I liked to sail alone. The sea was the same as a girl to me I did not want anyone else along.

Lacking instruction, I invented ways of getting things done, and usually ended by doing them in a rather queer fashion, and so did not learn to sail properly, and still cannot sail well, although I have been at it all my life. I was twenty before I discovered that charts existed; all my navigating up to that time was done with the wariness and the ignorance of the early explorers. I was thirty before I learned to hang a coiled halyard on its cleat as it should be done. Until then I simply coiled it down on deck and dumped the coil. I was always in trouble and always returned, seeking more trouble. Sailing became a compulsion: there lay the boat, swinging to her mooring, there blew the wind; I had no choice but to go. My earliest boats were so small that when the wind failed, or when I failed, I could switch to manual control-I could paddle or row home. But then I graduated to boats that only the wind was strong enough to move. When I first dropped off my mooring in such a boat, I was an hour getting up the nerve to cast off the pennant. Even now, with a thousand little voyages notched in my belt, I still I feel a memorial chill on casting off, as the gulls jeer and the empty mainsail claps.

The Cat Boat, Edward Hopper. 1922.

Of late years, I have noticed that my sailing has increasingly become a compulsive activity rather than a source of pleasure. There lies the boat, there blows the morning breeze-it is a point of honor, now, to go. I am like an alcoholic who cannot put his bottle out of his life. With me, I cannot not sail. Yet I know well enough that I have lost touch with the wind and, in fact, do not like the wind any more.

It jiggles me up, the wind does, and what I really love are windless days, when all is peace. There is a great question in my mind whether a man who is against wind should longer try to sail a boat. But this is an intellectual response-the old yearning is still in me, belonging to the past, to youth, and so I am torn between past and present, a common disease of later life.

When does a man quit the sea? How dizzy, how bumbling must he be? Does he quit while he's ahead, or wait till he makes some major mistake, like falling overboard or being flattened by an accidental jibe? This past winter I spent hours arguing the question with myself. Finally, deciding that I had come to the end of the road, I wrote a note to the boatyard, putting my boat up for sale. I said I was "coming off the water." But as I typed the sentence, I doubted that I meant a word of it.

If no buyer turns up, I know what will happen: I will instruct the yard to put her in again-"just till somebody comes along." And then there will be the old uneasiness, the old uncertainty, as the mild southeast breeze ruffles the cove, a gentle, steady, morning breeze, bringing the taint of the distant wet world, the smell that takes a man back to the very beginning of time, linking him to all that has gone before. There will lie the sloop, there will blow the wind, once more I will get under way. And as I reach across to the black can off the Point, dodging the trap buoys and toggles, the shags gathered on the ledge will note my passage. "There goes the old boy again," they will say. "One more rounding of his little Horn, one more conquest of his Roaring Forties." And with the tiller in my hand, I'll feel again the wind imparting life to a boat, will smell again the old menace, the one that imparts life to me: the cruel beauty of the salt world, the barnacle's tiny knives, the sharp spine of the urchin, the stinger of the sun jelly, the claw of the crab.

E.B. White (1899–1985) was an American essayist, poet, and author best known for Charlotte’s Web and his nearly 60 year career as a writer, then contributing editor, for The New Yorker, from its founding until his death.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1104044264?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Land of Ten Thousand Lakes"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

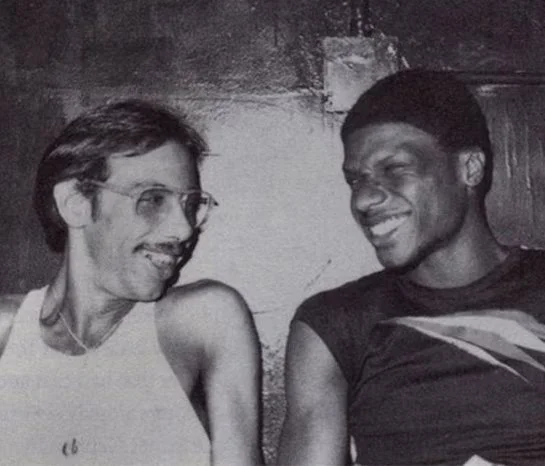

Ian Astbury

1h 41m

7.23.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Ian Astbury about becoming punk.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/stkgbywy/widget?token=4a0c6baf520c0211591690c5e50598ad" frameborder="0"></iframe>

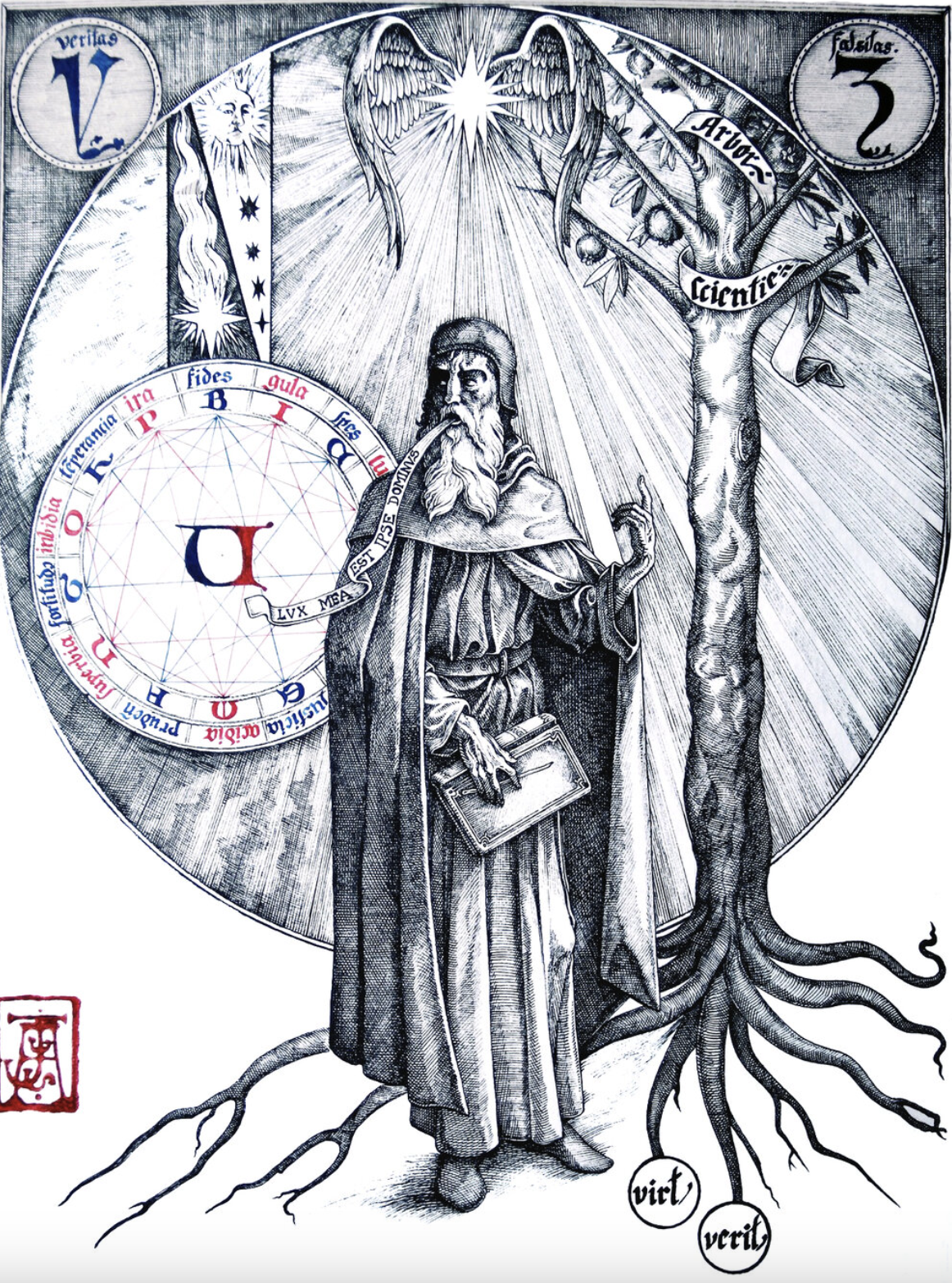

How Old Is The Sky? A Brief History Across Philosophies

Sander Priston July 22, 2025

Despite the ancient sounding ring to this rather abstract question, the first sign of an attempted answer in Western philosophy came only with the Moderns. Not the Stoics with their eternal return, nor the Christians with their metaphysical hesitations, it wasn’t until the 17th and 18th Centuries that two very different philosophers emerged with two very different answers to the question…

Sander Priston July 22, 2025

Despite the ancient sounding ring to this rather abstract question, the first sign of an attempted answer in Western philosophy came only with the Moderns. Not the Stoics with their eternal return, nor the Christians with their metaphysical hesitations, it wasn’t until the 17th and 18th Centuries that two very different philosophers emerged with two very different answers to the question.

The first came from a bishop named James Ussher, who in 1650 published Annales Veteris Testamenti - a chronology of the world using the Bible as a historical record. In this, he declared that the creation of the world — including the heavens and sky — occurred on

Sunday, 23 October, 4004 BC, at around 6:00 PM.

It is a strangely precise estimate for a first try, and implied the sky was roughly 6,000 years old in his time. This young sky abides by the Biblical notion that the earth and its heavens were invented for humanity’s sake.

65 years later, a natural philosopher watching molten iron cool in a furnace proposed a radically different answer. Edmond Halley, who famously predicted the date a comet would return decades before it did, used the salinity of the oceans and the rate of cooling of celestial bodies to estimate the sky's age.

In a 1714–1716 issue of the Philosophical Transactions, Edmond Halley presented what we now call the ‘salt clock’ method—using the rate of salt accumulation in the oceans to estimate the age of the Earth—and by implication, the atmosphere and sky. He declared that, “The sky is 75,000 years old. At least.”

Though Halley fell short of a definitive number like Ussher’s, he was among the first to suggest that a measurable, natural process could give us an empirical age of the cosmos. This kicked off the inquiry which led us to our most up-to-date estimate of ~13.8 billion years, reached through a combination of Cosmic microwave background radiation measurements (from missions like Planck and WMAP), Hubble’s law (expansion rate of the universe), and standard cosmological models (like ΛCDM).

Together, Ussher and Halley represent a major philosophical clash at the dawn of modern science. Ussher’s precise, scripture-based chronology reflected a worldview where the sky was young and created for humanity, while Halley’s naturalistic measurements hinted at a vast, ancient universe waiting to be understood through observation and reason.

Looking beyond Western thought, however, we find many interesting and creative attempts by philosophers at dating the age of the sky. In Hindu Cosmology, for example, the sky is 155.52 trillion years old.

In the Puranas and Mahabharata, important Hindu religious texts, time is structured into immense cosmic cycles. A kalpa (a "day of Brahma") is 4.32 billion years. A full cycle (including nights, years, lifetimes of Brahma) adds up to trillions of years. The current sky is said to be in the 51st year of Brahma, which places the age of this cycle of the universe at around 155.52 trillion years. The sky then has an age but no clear origin.

Madame Blavatsky, the 19th-century Russian-born mystic and founder of Theosophy, drew heavily on ancient Hindu cosmology and esoteric traditions to propose her own occultist answer, centered on the concept of “Manvantaras” — vast cosmic cycles. These cycles are measured in millions to billions of years, though Blavatsky’s calculations are symbolic and allegorical rather than scientific.

In her major work, The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky described Earth’s spiritual and physical evolution as unfolding through seven Root Races, or stages in humanity’s development, each corresponding metaphorically to vast astrological ages governed by star-beings. The Hindu-inspired cycles she describes imply a sky that is billions of years old, with a Mahayuga (Great Age) lasting 4.32 million years and a Day of Brahma lasting 4.32 billion years (1,000 Mahayugas).

Some Chinese Daoist alchemical texts, especially those concerned with immortality and the “Great Year” (da nian), describe time as cyclical in units of 129,600 years — tied to astronomical and numerological systems. The Taiyi Shengshui (The One Gave Birth to Water) and works like Huainanzi talk of sky and earth co-arising from primal qi, but some traditions suggest skies are reborn every great cycle. So the sky has a reset button, and its age is the circumference of a cosmic breath: 129,600 years.

In Zoroastrian cosmology, the universe is laid out across a 12,000-year timeline, divided into 4 epochs of 3,000 years. The sky (or firmament) was created in the second epoch, after the spiritual world but before humanity. So the sky is roughly 9,000 years old in this system – it was built in Year 3,000 and will collapse by Year 12,000.

“The sky, to our eyes, may rise, set, storm, and clear but this is theater, not ontology. The real sky — if such a thing exists — cannot age, because it does not become. It simply is.”

Our question, then, was considered across ancient cultures so why did no answer appear in Western thought prior to the Modern Period? For the Ancients, the reason is likely that they didn’t separate the sky from the cosmos. Asking “how old is the sky?” was like asking “How old is the stage before the play?” Time was something the sky measures, not something the sky experiences. As the realm of gods, stars, or divine harmony, giving it a number would be like putting a birthday on Zeus.

We see this in Plato, for whom the sky is not in time — time is in the sky; it is the first clock. Its age is synonymous with the very concept of age. For the Stoics, the sky has died a thousand times and will live again (ekpyrosis). It has no age because it is incapable of ceasing to be. It is a loop, not a line.

In many mythologies, the sky is not a natural object, but a deliberate covering — a veil stretched taut by the gods to conceal the raw machinery of existence. In Babylonian myth, Marduk slays the chaos-dragon Tiamat and stretches her body across the heavens to form the sky — a grim, cosmic tarp made of vanquished disorder. In Genesis, the firmament is created to divide the waters above from the waters below — a protective dome that makes human life possible. The sky is a curtain drawn for our benefit.

Gnostic texts, like On the Origin of the World and Apocryphon of John, consider the sky a deception – a rotating dome ruled by false gods (archons) who trap souls below it. The sky’s age is the length of our captivity — its number is how long we’ve been asleep.

Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), a cryptographer-monk-mystic, wrote about celestial intelligences controlling the world in 800-year periods, rotating like gears — a secret calendar with no age, but a coded rhythm

Some of the most interesting philosophies of the sky come from pre-Socratic philosophers. Their fragmentary insights, handed down in cryptic scraps, do not ask for an age, but rather what the sky is, and how it comes to be. They all answered our question in their own way — not with numbers, but with metaphors of fire, breath, rhythm, and ruin.

For Parmenides, the sky had no age. All that exists is Being, and Being does not change. Time, movement, growth, decay — these are illusions conjured by unreliable senses. If we trust only reason, we must conclude that what is, always was and always will be. There is no birth or death, past or future. Only the eternal, seamless Now. If the sky is, then it has no age, because age presumes change — a before and after. But there is no before and after in truth.

The sky, to our eyes, may rise, set, storm, and clear but this is theater, not ontology. The real sky — if such a thing exists — cannot age, because it does not become. It simply is. And if the sky as we perceive it is part of the grand illusion of Becoming, then the question of its age is a nonsense question — like asking for the temperature of a mirage.

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 500 BCE), known as the “weeping philosopher,” suggested a cosmos of ever-living fire. For him, the world — including the heavens — was not created, nor static, but constantly in flux:

“The cosmos, the same for all, was not made by gods or men, but always was and is and will be: an ever-living fire.”

For Heraclitus, to ask for the age of the sky is like asking the age of a flame. The fire exists because it burns. It is always old and always new. If there is time, it’s cyclical — the sky is not a container but a process: always kindling, always extinguishing, always returning.

Anaximenes of Miletus (c. 6th century BCE) conceived of the sky as breath. Air (aēr), he proposed, was the source of everything. The stars and sky condensed from rarefied air; the world breathing in and out.

“Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so breath and air encompass the whole world.”

The sky was of organic origin, made of the same stuff as soul. Its “age” is not historical but elemental. If breath is continuous, then the sky is not old in years, but eternally emerging, an exhalation of the cosmos.

For Anaximander, a shadowy figure who may have drawn the first map of the earth, the sky is a wound in the boundless. He imagined the universe emerging from the apeiron, indefinite and boundless. Worlds rise and fall from it in cycles, like bubbles in water. He conceived of celestial bodies as wheels of fire, partially obscured by mist, with visible light shining through holes — the stars and sun are leaks in the firmament.

“Things perish into those things out of which they came to be, according to necessity.”

Anaximander gives us a sky with not one beginning and an end, but many. Skies emerge and dissolve in cycles like peeling skins off an onion, each cosmos reveals another behind it.

Pythagorean cosmology understood the heavens as music — spheres turning in mathematically perfect harmony. Planets were believed to emit tones as they moved, inaudible to human ears: the “music of the spheres.” Here, the sky is not aged like an object but measured like a chord. It is timeless in the way a song is: you may experience part of it, but it exists all at once, in ideal form.

Today, our scientific understanding of the sky’s billion year existence tends to conjure up dread about our human insignificance. But history teaches us the enormity of varying reactions to the belief that the sky is ancient. As our own living philosopher Thomas Nagel pithily puts it, ridiculing existentialism, “suppose we lived forever; would not a life that is absurd if it lasts seventy years be infinitely absurd even if it lasted through eternity?”

Our internet-age nihilism is expertly mocked by Nagel, whose optimistically objective “view from nowhere” just looks like an overcast Tuesday. The sky can be meaningful, he insists, even when drab. Sure it may be indifferent to us, but if it’s going to hang over us all our lives then we may as well recognise the meaning it has had for others and project a bit of our own selves onto it. Maybe time to get offline and engage in a more meaningful, non-digital kind of looking up.

Sander Priston is a busking philosopher, journalist, and musician.

Film

<div style="padding:73.63% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1102879432?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Rope clip 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1103061262?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Carlo Rovelli on The Order of Time clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Larry Levan Playlist

Archival 1967-1987

Larry Levan was an influential American DJ who defined what modern dance clubs are today. He is most widely renowned for his long-time residency at Paradise Garage, also known as “Gay-Rage”, a former nightclub at 84 King Street in Manhattan, NY.

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - July 10, 2025

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1102882854?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Smokey the Bear, 1952"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Tower (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 19, 2025

In the Tower we find the dual nature of energy perfectly expressed as creation and destruction. What Man makes, God shall destroy, what God makes, Man shall destroy…

Name: The Tower, the House of God

Number: XVI

Astrology: Mars

Qabalah: Pe, the Mouth

Chris Gabriel July 19, 2025

In the Tower we find the dual nature of energy perfectly expressed as creation and destruction. What Man makes, God shall destroy, what God makes, Man shall destroy. This is the Tower of Babel and the endlessly repeating Fall of Man. In each, divine fire destroys the high tower, and the inhabitants plummet below.

In Rider, a black sky is torn by a lightning strike. A bolt has thrown off the golden crown from atop a high stone tower with three windows. Flames devour what remains. Two royals fall below and little yellow yods rain from the clouds.

In Thoth, we have a rather cubist image; a tower warping down, the maw of Hell spitting out flames while an unblinking eye in the sky looks on as figures jump from the high tower. In the sky dwell a dove and a serpent (the lion headed snake god Ialdabaoth, the evil god of the world according to Gnostic Christians).

In Marseille, it is an almost playful scene, a feathery ray rips the crown off the tower, while two figures fall, their hands just touching the earth. Colorful balls fall along the three-windowed tower.

These are three very different depictions: one playful, one tragic, one horrific. Each is valid. Marseille strongly calls to mind the insight of Heraclitus; that God is but a child playing with toys. We have seen this juvenile God playfully make dolls kiss in the Lovers, but here we see the divine child knock down the blocks he’s been stacking.

Mankind cannot accept its own ephemeral nature. It desperately tries to create lasting works, to erect expressions of itself, contradictory to the natural flux of God. The Tower is simply God laughing at these vain attempts. We try to escape our nature in lofty ideas, but God kindly brings us back down to the earth.

As Mars, this card is the complement to the Empress’ Venus. The Empress maternally cultivates, protects, and grows while the Tower razes, attacks, and undoes. In this way, they are perfectly balanced. The Dove and the Serpent.

This duality is prominent in Christianity, the spiritual basis of Marseille, and in Thelema, the basis of Thoth.

Love is the law, love under will. Nor let the fools mistake love; for there are love and love. There is the dove, and there is the serpent. Choose ye well!

-Book of the Law I:57

Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.

-Matthew 10:16

This card answers one of the greatest difficulties of believers: why do bad things happen?

Simply because God wills it, because it amuses God, so says Nietzsche in Genealogy of Morals:

It is certain, at any rate, that the Greeks still knew of no tastier spice to offer their gods to season their happiness than the pleasures of cruelty. With what eyes do you think Homer made his gods look down upon the destinies of men? What was at bottom the ultimate meaning of Trojan Wars and other such tragic terrors? There can be no doubt whatever: they were intended as festival plays for the gods.

It is our own fear that manufactures the desire for a “Good” (according to our human morals) God, rather than accepting God as such. The Tarot is meant to be a complete image of God, a cosmogram. As such, it contains both the infinite love and infinite violence of a whole universe.

In the human sphere, this card is often directly sexual. When social facades crumble, the natural drives express themselves, either with the passion of sex, or violence. This can indicate that your well laid plans will go awry and the unexpected will occur. When we are aligned with the universe, this tends to be a pleasant surprise rather than a wretched accident.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1102130377?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Firing Line clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Divine Warriors and Villains (Pronoia Pt. 3)

Molly Hankins July 17, 2025

We all have different roles to play in the great human drama advancing the plot of our evolution. A pronoia-informed perspective invites us to consider the possibility that characters we fear or dislike might be playing critical parts in our stories…

Kalīlah wa-Dimnah, ca. 1525–50.

Molly Hankins July 17, 2025

We all have different roles to play in the great human drama advancing the plot of our evolution. A pronoia-informed perspective invites us to consider the possibility that characters we fear or dislike might be playing critical parts in our stories. Pronoia author Rob Breszney’s worldview is that of a benevolent, conscious universe, one conspiring to facilitate evolutionary opportunities for our highest good and sometimes greatest delight. Those we perceive as enemies are often our greatest teachers and Breszney believes we owe them a debt of gratitude for “sharpening our wits and and sculpting our souls.” How could the universal conspiracy to give us exactly what our souls need operate without the plot twists facilitated by seemingly bad actors?

Breszney writes, “Imagine the people you fear and dislike as pivotal characters in a fascinating and ultimately redemptive plot that will take years or even lifetimes to elaborate.” By offering gratitude to those characters, we can neutralize our innate, egoic reaction to them and instead grease the wheels of evolution by welcoming their teachings. Kabbalah recommends responding to any stimulus that elicits a negative reaction by consciously pausing, followed by saying, “What a gift!” It can be said out loud or simply to yourself, but it’s an essential part of rewiring our perspective away from paranoia and towards pronoia. With practice it becomes muscle memory, and a means of washing our own brains to default to pronoia.

Those souls willing to play the villain are actually doing a great service,sacrificing their ego to play the part. By asking ourselves why someone is in our life story and what archetype they’re playing, we zoom out from the minutia of human drama and start to see such patterns as part of a greater cycle of life. Perhaps this moment of disidentification is all we need to be able to move with, “...the shifting conditions of the Wild Divine’s ever-fresh creation,” instead of fighting the flow. Practicing pronoia simply means training our perception to perceive life as giving us exactly what we need, exactly when we need it. To perceive our enemies as old, soul friends playing a tough part in our story is to both neutralize the emotional effect they have on us and to send them love.

Without villains, how can the hero become the warrior?? Breszney recommends always thanking our adversaries for the crucial roles they’ve played in our lives and believes we owe extra gratitude to those we feel have slowed us down. By causing blockage or delay in our journey these people are actually preventing things from happening too fast, which is often impossible to perceive as it’s happening. “Imagine that the evolution of your life or our culture is like a pregnancy: it needs to reach its full term,” he wrote. Life has its own timing and when we sync up with it we can feel it. This is the flow-state, and it’s often punctuated by an uptick in synchronicities and what the untrained eye might call coincidences.

Cultivating flow and authentic presence is a feature of the warrior archetype, which according to Tibetan texts, has four features of dignity.

Relaxed confidence (often mistranslated as “meekness”)

Relentless joy (perkiness)

Outrageousness (which can help us overcome both fear and hope)

Inscrutability (inability to be pinned down by a label that would only limit the warrior)

Many of us may play the villain in the story of another without meaning to or even realizing it, a reminder that our souls play every part, often in the same lifetime. By consciously cultivating the above features of dignity through focused attention, we wash our brains to act more in the interest of our higher, heroic warrior nature. Even if we’re playing the villain and stooping to our lower, animal nature in the process. however, we can still live in what Breszney calls “alignment with the infinity of the moment.” To be aligned with the infinity of the moment is to revel in pronoia as a practice.

He writes, “Even if some of us are temporarily in the midst of trial or tribulation, human evolution is proceeding exactly as it should, even if we can’t see the big picture of the puzzle that would clarify how all the pieces fit together perfectly.” Pronoia is not about absolute truth, which us humans don’t fully get to know anyway. It is about utility. Believing the universe is conspiring in our favor is useful because it’s empowering and accounts for the influence we have on reality just by perceiving it. As the book ends Breszney leaves readers with the assignment to imagine everything in the world belongs to us and take good care of it, the way we want others to.

“And make sure you also enjoy the level of fun that comes with such mastery,” he encourages us. “Glide through life as if all of creation is yearning to honor and entertain you.”

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1102878385?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Jane Eyre clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Alex Spiro

1h 7m

7.16.25

In this clip, Rick speaks with Alex Spiro about cynicism in law.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/jwg0t5n5/widget?token=4252c06921d5985e6727cd60c5f75af4" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1102124578?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Personal Legacies- Materiality and Abstraction clip 8"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>