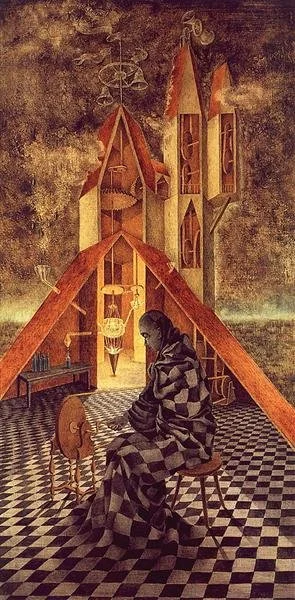

Useless Science, or The Alchemist

VARO

One of the ‘Three Witches of Surrealism’, Remedios Varo searched constantly for hidden knowledge. She accessed worlds beyond physical comprehension and translated these in a heady blend of oil and canvas. A female alchemist draped in the checkerboard ground she sits upon turns a wheel towards eternal life. The smoke seems to escape the painting and pollute our world while the bell tower disappears behind the canvas. “I deliberately set out to make a mystical work”, said Varo, “in the sense of revealing a mystery, or better, of expressing it through ways that do not always correspond to the logical order, but to an intuitive, divinatory and irrational order”.

REMEDIOS VARO

REMEDIOS VARO, 1958

One of the ‘Three Witches of Surrealism’, Remedios Varo searched constantly for hidden knowledge. She accessed worlds beyond physical comprehension and translated these in a heady blend of oil and canvas. A female alchemist draped in the checkerboard ground she sits upon turns a wheel towards eternal life. The smoke seems to escape the painting and pollute our world while the bell tower disappears behind the canvas. “I deliberately set out to make a mystical work”, said Varo, “in the sense of revealing a mystery, or better, of expressing it through ways that do not always correspond to the logical order, but to an intuitive, divinatory and irrational order”.

Ravens

FUKASE

Masahisa Fukase desperately sought control. Both the first and second wives of the 'anti-self-portraitist' suffered under his incessant, obsessive documentation of their likenesses. It was only after his second divorce, returning on the mournful JE-train from Tokyo to his hometown of Hokkaido, that Fukase first glimpsed what was to become his defining obsession. Collected first as ‘The Solitude of Ravens’, the original title explains much of Fukase's intention - wallowing in depressive bachelorhood. The photographer spent the next eleven years in his birthplace, spiralling through his ceaseless fascination with its growing population of ‘ravens’. In all fact, the majority of the birds were anything but - for Hokkaido has few raven roosts, outnumbered in their hundreds by the myriad crows. It was the idea of ravens that compelled Fukase; in 1982, his journal read “karasu ni nata (I have become a raven)”.

MASAHISA FUKASE

MASHISA FUKASE, 1977

Masahisa Fukase desperately sought control. Both the first and second wives of the 'anti-self-portraitist' suffered under his incessant, obsessive documentation of their likenesses. It was only after his second divorce, returning on the mournful JE-train from Tokyo to his hometown of Hokkaido, that Fukase first glimpsed what was to become his defining obsession. Collected first as ‘The Solitude of Ravens’, the original title explains much of Fukase's intention - wallowing in depressive bachelorhood. The photographer spent the next eleven years in his birthplace, spiralling through his ceaseless fascination with its growing population of ‘ravens’. In all fact, the majority of the birds were anything but - for Hokkaido has few raven roosts, outnumbered in their hundreds by the myriad crows. It was the idea of ravens that compelled Fukase; in 1982, his journal read “karasu ni nata (I have become a raven)”.

The Silueta Series

MENDIATA

‘My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source’, said Mendieta, ‘Through my earth/body sculptures, I become one with the earth’. Yet it is hard to look at these works of unity and not see harbingers of death. Here, Mendieta’s body is made of algae on the shore of an anonymous marsh. Reminiscent of Ophelia drowning, the silhouette could just as easily be mistaken as a natural form as it could a body washed ashore. Mendieta created her silhouettes from water, plants, fire, rock and the natural world around her. In leaving her imprint, she has to engage in the abstract imagery of violence. She becomes a spirit, a whisper of a body no longer there.She embodies nature by mimicking death.

ANA MENDIETA

ANA MENDIETA, 1979

‘My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source’, said Mendieta, ‘Through my earth/body sculptures, I become one with the earth’. Yet it is hard to look at these works of unity and not see harbingers of death. Here, Mendieta’s body is made of algae on the shore of an anonymous marsh. Reminiscent of Ophelia drowning, the silhouette could just as easily be mistaken as a natural form as it could a body washed ashore. Mendieta created her silhouettes from water, plants, fire, rock and the natural world around her. In leaving her imprint, she has to engage in the abstract imagery of violence. She becomes a spirit, a whisper of a body no longer there.She embodies nature by mimicking death.

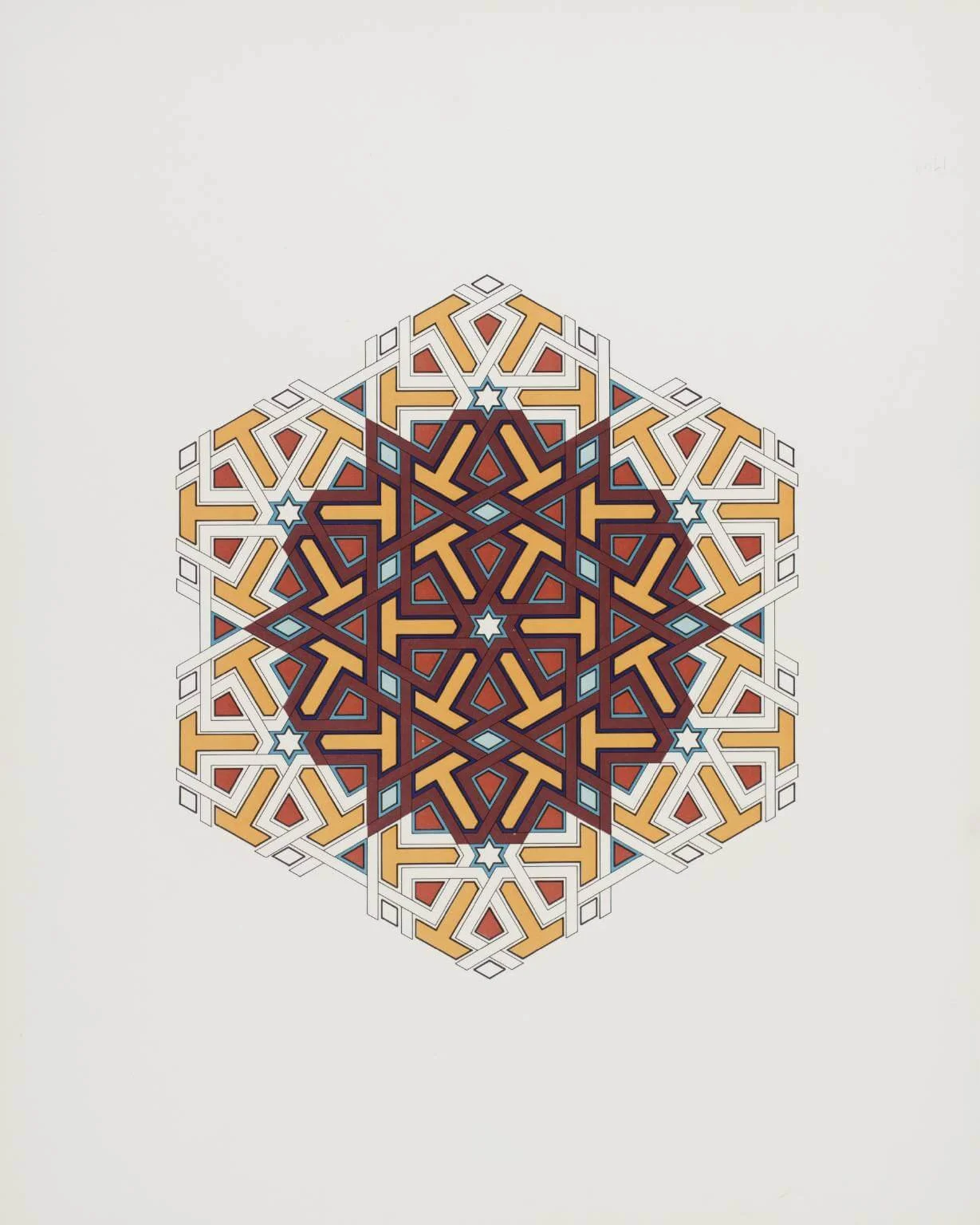

Nasr

CRITCHLOW

When the Minbar of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem was damaged in an arson attack, the ancient knowledge of how to map the structure geometrically was long considered lost. A 30 year search led to a an engineer stumbling across Keith Critchlow’s book ‘Islamic Patterns’ in a bookstore in Damascus, and found the book contained the answers of the ancient sacred geometry. A British Artist an academic, from a group of abstract expressionists, Critchlow became a student of Buckminster Fuller and eventually the world’s leading authority on Islamic and Sacred Geometry. For Critchlow, Mathematics and Geometry was the highest form of art, and art was the was direct link to higher power.

KEITH CRITCHLOW

KEITH CRITCHLOW, 1976

When the Minbar of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem was damaged in an arson attack, the ancient knowledge of how to map the structure geometrically was long considered lost. A 30 year search led to an engineer stumbling across Keith Critchlow’s book ‘Islamic Patterns’ in a bookstore in Damascus, and found the book contained the answers to the ancient sacred geometry. A British artist and academic, Critchlow was in a group of abstract expressionists before he became a student of Buckminster Fuller and eventually the world’s leading authority on sacred Islamic geometry. For Critchlow, mathematics and geometry were the highest forms of art, and art was the direct link to higher power.

And Then We Saw The Daughters of the Minotaur

CARRINGTON

Leonora Carrington freed herself from multiple worlds. Born into English aristocracy, she ran away to Paris to join the Surrealists, and then later to Mexico City where she worked prolifically but with little recognition. Her constant escape, however, was to her dreams, a higher plane of her reality. When she awoke she captured ethereal, fleeting, subconscious ideas on canvas. In a clouded room, nature, mysticism and the human meet. Her two sons stand at the table of a minotaur and a flowering mothlike deity. We have interrupted a scene, and are given only a glimpse of a world beyond our comprehension. Carrington paints fragments of a world only she can know: ‘I’ve always had access to other worlds. We all do. Because we dream’.

LEONARA CARRINGTON

LEONARA CARRINGTON, 1953

Leonora Carrington freed herself from multiple worlds. Born into English aristocracy, she ran away to Paris to join the Surrealists, and then later to Mexico City where she worked prolifically but with little recognition. Her constant escape, however, was to her dreams, a higher plane of her reality. When she awoke she captured ethereal, fleeting, subconscious ideas on canvas. In a clouded room, nature, mysticism and the human meet. Her two sons stand at the table of a minotaur and a flowering mothlike deity. We have interrupted a scene, and are given only a glimpse of a world beyond our comprehension. Carrington paints fragments of a world only she can know: ‘I’ve always had access to other worlds. We all do. Because we dream’.

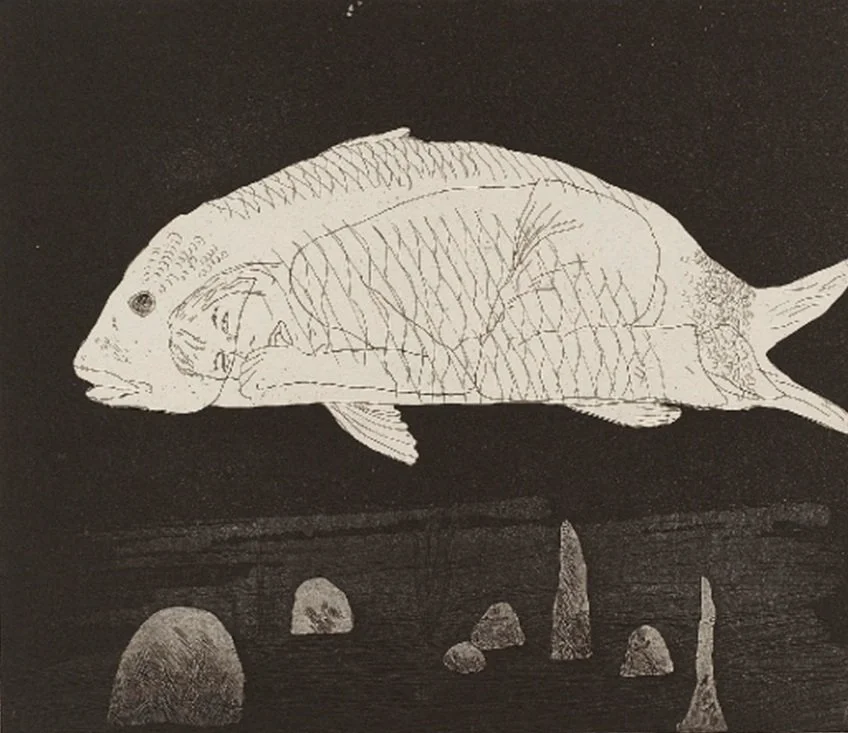

The Boy Hidden in a Fish

HOCKNEY

David Hockney had long been enthralled by the Brothers Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The stories are strange and magical, dealing in the mystic and the moral but told in straightforward, simple language. He set about creating 39 etchings that illustrated six stories, including ‘The Little Sea Hare’, from which this work takes its inspiration. In the story, a boy hides from a princess in the belly of a fish to avoid execution. Using his studio assistant as a model, Hockney’s figure exists between peace and fear, an embryonic pose and a sucked thumb bringing his grown body into a childlike pose. In the darkness, the empty stare of a bright white fish and the quietness of a hiding boy seem to speak to eternity, not to death.

DAVID HOCKNEY

DAVID HOCKNEY, 1969

David Hockney had long been enthralled by the Brothers Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The stories are strange and magical, dealing in the mystic and the moral but told in straightforward, simple language. He set about creating 39 etchings that illustrated six stories, including ‘The Little Sea Hare’, from which this work takes its inspiration. In the story, a boy hides from a princess in the belly of a fish to avoid execution. Using his studio assistant as a model, Hockney’s figure exists between peace and fear, an embryonic pose and a sucked thumb bringing his grown body into a childlike pose. In the darkness, the empty stare of a bright white fish and the quietness of a hiding boy seem to speak to eternity, not to death.

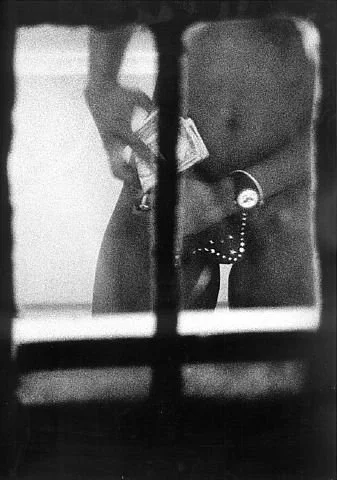

Dirty Windows

ALPERN

When Merry Alpern found out her friend’s bathroom window looked out onto the bathroom window of an illegal brothel, she set up camp. Hitchcock’s Rear Window had come true, and she spent a year taking grainy photos of illicit scenes. Painfully aware of the immorality of her voyeurism, the glimpses of a hidden world she saw kept bringing her back. The framing of the images was necessitated by the chance positioning of the window, but you couldn’t have asked for a better position. A narrative is told in minutiae – we glimpse a life we do not live and tell a story to ourselves.

MERRY ALPERN

MERRY ALPERN, 1993–1994

When Merry Alpern found out her friend’s bathroom window looked out onto the bathroom window of an illegal brothel, she set up camp. Hitchcock’s Rear Window had come true, and she spent a year taking grainy photos of illicit scenes. Painfully aware of the immorality of her voyeurism, the glimpses of a hidden world she saw kept bringing her back. The framing of the images was necessitated by the chance positioning of the window, but you couldn’t have asked for a better position. A narrative is told in minutiae – we glimpse a life we do not live and tell a story to ourselves.

Walnut Stools

EAMES

In 1960, Charles and Ray Eames were commissioned to design furnishings for the new Time Life Building lobby. A site-specific desk made of solid walnut anchored the design, and provided the impetus for these turned stools. The Eames had never worked with solid wood before. They created three designs reminiscent of chess pieces. The top and bottoms remained consistent with alternative shaped wood middle systems. Charles and Ray intended the stools to be usable as side tables, making sure the concave top was deep enough to be comfortable, but ‘not so deep as to make it impossible to secure a teacup and saucer on it’. Small variations on elegant simplicity and an obsessive approach create a beauty that is obvious but an ingenuity nearly invisible.

CHARLES AND RAY EAMES

CHARLES AND RAY EAMES, 1960

In 1960, Charles and Ray Eames were commissioned to design furnishings for the new Time Life Building lobby. A site-specific desk made of solid walnut anchored the design, and provided the impetus for these turned stools. The Eames had never worked with solid wood before. They created three designs reminiscent of chess pieces. The top and bottoms remained consistent with alternative shaped wood middle systems. Charles and Ray intended the stools to be usable as side tables, making sure the concave top was deep enough to be comfortable, but ‘not so deep as to make it impossible to secure a teacup and saucer on it’. Small variations on elegant simplicity and an obsessive approach create a beauty that is obvious but an ingenuity nearly invisible.