Officer and the Laughing Girl

JOHANNES VERMEER

Vermeer’s work lives in the details. Look at the panes of glass, the white wall, the mundane features that for so many other artists serve but as dressing and decoration, considered for their contribution to the main subject but not given the time, respect, and obsession to bring out their quiet beauty. Vermeer was different – amongst the most technically gifted painters in history, he found the beauty in the everyday object and was obsessive in his pursuit to capture it. The light that falls through the open window creates an unparalleled variety of hues within the glass, and the wall moves from an ivory to an eggshell with such depth and subtlety that our eyes read it as reality. There are many theories as to how Vermeer was able to capture such profound detail and how he could seemingly understand light like no other before him, but one needs only to look at his paintings to understand that it was born out of a deep reverence for the everyday beauty he saw all around him.

Johannes Vermeer

JOHANNES VERMEER, c.1657. OIL ON CANVAS.

Vermeer’s work lives in the details. Look at the panes of glass, the white wall, the mundane features that for so many other artists serve but as dressing and decoration, considered for their contribution to the main subject but not given the time, respect, and obsession to bring out their quiet beauty. Vermeer was different – amongst the most technically gifted painters in history, he found the beauty in the everyday object and was obsessive in his pursuit to capture it. The light that falls through the open window creates an unparalleled variety of hues within the glass, and the wall moves from an ivory to an eggshell with such depth and subtlety that our eyes read it as reality. There are many theories as to how Vermeer was able to capture such profound detail and how he could seemingly understand light like no other before him, but one needs only to look at his paintings to understand that it was born out of a deep reverence for the everyday beauty he saw all around him.

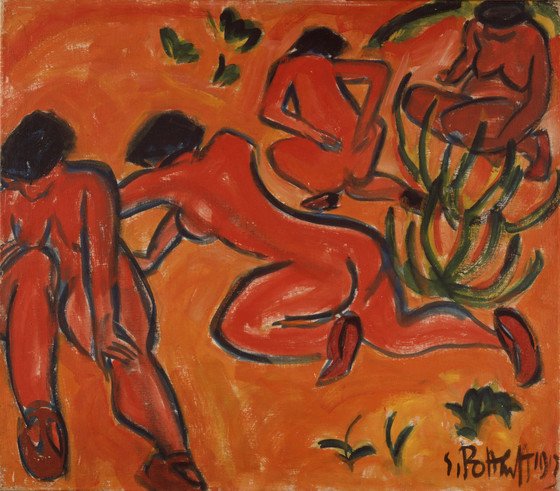

Bathers

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF

In an artists colony by the Baltic Sea, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and his colleagues within the German Expressionist group Die Brücke practiced a back to nature, free love, bohemian lifestyle. Their summers were as much an extension of their avant-grade art as their paintings were, living true to the same principles they applied to canvas. Nude bathers, taking the form of anonymous and objectified female forms, blend into a landscape with few signifiers save for sparse grass and loose dune like shapes. The image intentionally reveals little, it aspires instead to a universal sensation of summertime - the deep ochre acting as an oppressive sun that coats all it touches and the grit of the brushstrokes like the coarse grains of sand against the revellers bodies. Schmidt-Rottluff’s evocative images laid the groundwork for the Expressionists that followed him but few captured a lifestyle in harmony with their art quite so potently.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF, 1913. OIL ON CANVAS.

In an artists colony by the Baltic Sea, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and his colleagues within the German Expressionist group Die Brücke practiced a back to nature, free love, bohemian lifestyle. Their summers were as much an extension of their avant-grade art as their paintings were, living true to the same principles they applied to canvas. Nude bathers, taking the form of anonymous and objectified female forms, blend into a landscape with few signifiers save for sparse grass and loose dune like shapes. The image intentionally reveals little, it aspires instead to a universal sensation of summertime - the deep ochre acting as an oppressive sun that coats all it touches and the grit of the brushstrokes like the coarse grains of sand against the revellers bodies. Schmidt-Rottluff’s evocative images laid the groundwork for the Expressionists that followed him but few captured a lifestyle in harmony with their art quite so potently.

Portrait of Isaku Yanaihara

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

“I am not attempting likeness”, said Giacometti, “but resemblance”. After being interviewed Isaku Yanaihara, treating him as confidant and muse for the near decade that followed. He made over a dozen oil portraits and one sculpture of Yanaihara, and this is the second in his enduring series. The figure seems to appear as an apparition, ghostlike in the powerful glow that surrounds him. His body and face appear in allusions, confident brushstrokes that reveal little of detail but huge amounts of essence. In his sculptural work, Giacometti was a revolutionary who reinterpreted the human form into something otherworldly yet recognisable and the same quality appears in his paintings. Yanaihara is unrecognisable as an individual figure here, but a spirit of the man seems to shine through the canvas. His physicality disappears into thick oil paint leaving only the truth of his personality behind.

Alberto Giacometti

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI, 1956. OIL ON CANVAS.

“I am not attempting likeness”, said Giacometti, “but resemblance”. After being interviewed Isaku Yanaihara, treating him as confidant and muse for the near decade that followed. He made over a dozen oil portraits and one sculpture of Yanaihara, and this is the second in his enduring series. The figure seems to appear as an apparition, ghostlike in the powerful glow that surrounds him. His body and face appear in allusions, confident brushstrokes that reveal little of detail but huge amounts of essence. In his sculptural work, Giacometti was a revolutionary who reinterpreted the human form into something otherworldly yet recognisable and the same quality appears in his paintings. Yanaihara is unrecognisable as an individual figure here, but a spirit of the man seems to shine through the canvas. His physicality disappears into thick oil paint leaving only the truth of his personality behind.

Portrait of Sebastià Junyer Vidal

PABLO PICASSO

As he sunk into depression, catalysed by the suicide of a close friend, Picasso entered one of his most celebrated and devastating eras – what is now known as his ‘Blue Period’. From 1901 to 1904, his paintings became monochromatic, depicting all manner of subjects in shades of blue with irregular spots of bright colour that seem to break through the morose monotony of the rest of the canvas. The cool hues make the content of the work seem detached; a sadness pervades every corner as Picasso’s inner life bleeds into his creation. As the period developed, he moved towards painting outsiders in society – sex workers, beggars, and down-and-outs – and increasingly became one himself. The blue work inspired little affection from the buying public and Picasso’s fortunes, which at the turn of the century had seemed so bright, turned for the worse. He became the outsiders he painted, and so much of Picasso’s wildly successful career that followed originated in both the work and the experiences of this difficult time.

Pablo Picasso

PABLO PICASSO, 1903. OIL ON CANVAS.

As he sunk into depression, catalysed by the suicide of a close friend, Picasso entered one of his most celebrated and devastating eras – what is now known as his ‘Blue Period’. From 1901 to 1904, his paintings became monochromatic, depicting all manner of subjects in shades of blue with irregular spots of bright colour that seem to break through the morose monotony of the rest of the canvas. The cool hues make the content of the work seem detached; a sadness pervades every corner as Picasso’s inner life bleeds into his creation. As the period developed, he moved towards painting outsiders in society – sex workers, beggars, and down-and-outs – and increasingly became one himself. The blue work inspired little affection from the buying public and Picasso’s fortunes, which at the turn of the century had seemed so bright, turned for the worse. He became the outsiders he painted, and so much of Picasso’s wildly successful career that followed originated in both the work and the experiences of this difficult time.

Purification of the Temple

EL GRECO

An angry Christ drove the moneychangers out of the Temple, flipping their tables in disgust at the heresy they showed. Though one of the most common contemporary stories from the New Testament, it was not a popular theme of painting for most of the Renaissance, presenting a side of Christ that seemed counter to the beauty and divinity so much of the work strove for. Yet El Greco returned to this subject multiple times throughout his career, and at the turn of the 1600s, it began to take on radically new meaning. As Protestantism began to rise across Europe, the Catholic Church saw this story as an analogy for their attempt to purify themselves from the scourge of this new religion. Protestantism was, for them, the heresy to true Christianity, and Christ driving the moneychangers out was inspiration for them to keep the Catholic faith pure and alive.

El Greco

EL GRECO, c.1600. OIL ON CANVAS.

An angry Christ drove the moneychangers out of the Temple, flipping their tables in disgust at the heresy they showed. Though one of the most common contemporary stories from the New Testament, it was not a popular theme of painting for most of the Renaissance, presenting a side of Christ that seemed counter to the beauty and divinity so much of the work strove for. Yet El Greco returned to this subject multiple times throughout his career, and at the turn of the 1600s, it began to take on radically new meaning. As Protestantism began to rise across Europe, the Catholic Church saw this story as an analogy for their attempt to purify themselves from the scourge of this new religion. Protestantism was, for them, the heresy to true Christianity, and Christ driving the moneychangers out was inspiration for them to keep the Catholic faith pure and alive.

The Opera 'Messalina' at Bordeaux

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

Toulouse-Lautrec captured the decadence of his age. The publicity, the cabaret, the drama, the cafes, the restaurants and the spectacle of the turn of the century exudes from his oeuvre, capturing the subtleties and lack thereof that he lived within. The Opera was a recurring theme for him, sexually charged, high society drama replete with costumes and theatre – the subject and the painter were natural bedfellows. Born into aristocracy, a childhood accident rendered him very short as an adult due to his undersized legs and in Paris he found more comfort and kindness in the brothels and bars than the upper-class world of his birth. Yet he participated in both, an outsider who was allowed in and could keenly observe the idiosyncrasies and beauty of these mirroring existences.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC, 1900. OIL ON CANVAS.

Toulouse-Lautrec captured the decadence of his age. The publicity, the cabaret, the drama, the cafes, the restaurants and the spectacle of the turn of the century exudes from his oeuvre, capturing the subtleties and lack thereof that he lived within. The Opera was a recurring theme for him, sexually charged, high society drama replete with costumes and theatre – the subject and the painter were natural bedfellows. Born into aristocracy, a childhood accident rendered him very short as an adult due to his undersized legs and in Paris he found more comfort and kindness in the brothels and bars than the upper-class world of his birth. Yet he participated in both, an outsider who was allowed in and could keenly observe the idiosyncrasies and beauty of these mirroring existences.

Young Woman of the People

AMEDEO MODIGLIANI

At the turn of the century, African Art began to be imported into Europe and by the mid 1910s, it was flooding Paris. So many of the era’s greatest artists, from Picasso to Cezanne, were inspired by the sculptural, ethereal faces of these masks, and each interpreted the aesthetic philosophy in a different way. Modigliani, a young Italian painter who was to die at the age of 35 with little commercial success, combined an inspiration from the masks with a deep understanding of the antiquity and Italian Renaissance paintings that he had studied as an adolescent. The resulting works are surreal and modern, elongated figures with his trademark almond faces seem to exist outside of time, the women painted become a bridge between centuries and continents. It was only five years before his death that the synthesis of his two founding influences reached its apex and created one of the most distinctive styles of portraiture. Modigliani’s paintings are piercing and uncanny, works of a strange nature that lure you in.

Amedeo Mogiliani

AMEDEO MODIGLIANI, 1918. OIL ON CANVAS.

At the turn of the century, African Art began to be imported into Europe and by the mid 1910s, it was flooding Paris. So many of the era’s greatest artists, from Picasso to Cezanne, were inspired by the sculptural, ethereal faces of these masks, and each interpreted the aesthetic philosophy in a different way. Modigliani, a young Italian painter who was to die at the age of 35 with little commercial success, combined an inspiration from the masks with a deep understanding of the antiquity and Italian Renaissance paintings that he had studied as an adolescent. The resulting works are surreal and modern, elongated figures with his trademark almond faces seem to exist outside of time, the women painted become a bridge between centuries and continents. It was only five years before his death that the synthesis of his two founding influences reached its apex and created one of the most distinctive styles of portraiture. Modigliani’s paintings are piercing and uncanny, works of a strange nature that lure you in.

Tea

HENRI MATISSE

In the years after the first World War, Matisse’s wild Fauvism waned, and he became less concerned with translating his pure expressions through brushstrokes and developed into a more sophisticated style. ‘Tea’ is the largest and amongst the most accomplished of this period, with touches of Impressionism in the dappled sunlight and broad strokes, it communicates the lushness and comfort of the scene with clarity and beauty. Yet look a little deeper and we see further clues of Matisse’s radical origins. The face of Marguerite is distorted and in the style of the African masks that both Matisse and Picasso found so much inspiration in. It is an extension of his seminal sculptures that increasingly abstracted a female face, yet here in exists in domestic harmony, less radical and more a part of everyday life. Matisse’s revolution was accepted by the world, and this painting is testament to it’s integration in daily life.

Henri Matisse

HENRI MATISSE, 191. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the years after the first World War, Matisse’s wild Fauvism waned, and he became less concerned with translating his pure expressions through brushstrokes and developed into a more sophisticated style. ‘Tea’ is the largest and amongst the most accomplished of this period, with touches of Impressionism in the dappled sunlight and broad strokes, it communicates the lushness and comfort of the scene with clarity and beauty. Yet look a little deeper and we see further clues of Matisse’s radical origins. The face of Marguerite is distorted and in the style of the African masks that both Matisse and Picasso found so much inspiration in. It is an extension of his seminal sculptures that increasingly abstracted a female face, yet here in exists in domestic harmony, less radical and more a part of everyday life. Matisse’s revolution was accepted by the world, and this painting is testament to it’s integration in daily life.

Portrait of Thomas Cromwell

HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER

Thomas Cromwell was a layman, the son of brewer, who worked his way up English society to be the right- hand man of King Henry VIII and one of the architects of the Reformation. His power would not last and he was ultimately executed by the King after an ill-fated plan of marriage lost the monarch popularity. But at the height of his powers, Cromwell commissioned Hans Holbein, the irregular court painter of Henry VIII, to paint this portrait of himself. Some 5 years earlier, Holbein had painted a remarkably similar portrait of Thomas More, Cromwell’s counterpart on the other side of the reformation and his sworn enemy. Yet in the years since More’s portrait was painted, Cromwell had helped engineer his downfall and when he came to commission his own, it is hard not to read it as a snub against his conquered enemy.

Hans Holbein The Younger

HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER, c.1532. OIL ON PANEL.

Thomas Cromwell was a layman, the son of brewer, who worked his way up English society to be the right- hand man of King Henry VIII and one of the architects of the Reformation. His power would not last and he was ultimately executed by the King after an ill-fated plan of marriage lost the monarch popularity. But at the height of his powers, Cromwell commissioned Hans Holbein, the irregular court painter of Henry VIII, to paint this portrait of himself. Some 5 years earlier, Holbein had painted a remarkably similar portrait of Thomas More, Cromwell’s counterpart on the other side of the reformation and his sworn enemy. Yet in the years since More’s portrait was painted, Cromwell had helped engineer his downfall and when he came to commission his own, it is hard not to read it as a snub against his conquered enemy.

Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI

Following the death of Jesus Christ, Mary Magdalene retreated to a life of solitude and quiet penitence, communing privately with God through prayer. This period in life was a favourite subject of artists of the Renaissance, but it was Gentileschi who brought it to life. Her saintly attributes, an ornament jar, crucifix, and skull, that were traditionally included to help the viewer identify the subject are gone. She is not in a state of penitence or atonement, but in a moment of overwhelming ecstasy, taken with the spirit of God she enters into a deeply personal and powerful moment. Gentileschi brings her close to us, almost voyeuristically, to that we are in the room with her during this quiet moment. It is sensual, her bare skin exposed, and the work of a female painter, rare in the time of the Renaissance, is clear in her deft handling of the folds of skin and the strength of passion she feels, that never moves into eroticism. Gentileschi brings a private movement with God into the public, and does so in a way that feels relatable, familiar to us the viewer, thus encouraging us to lose ourselves in ecstasy with a higher power.

Artemisia Gentileschi

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI, c.1620. OIL ON CANVAS.

Following the death of Jesus Christ, Mary Magdalene retreated to a life of solitude and quiet penitence, communing privately with God through prayer. This period in life was a favourite subject of artists of the Renaissance, but it was Gentileschi who brought it to life. Her saintly attributes, an ornament jar, crucifix, and skull, that were traditionally included to help the viewer identify the subject are gone. She is not in a state of penitence or atonement, but in a moment of overwhelming ecstasy, taken with the spirit of God she enters into a deeply personal and powerful moment. Gentileschi brings her close to us, almost voyeuristically, to that we are in the room with her during this quiet moment. It is sensual, her bare skin exposed, and the work of a female painter, rare in the time of the Renaissance, is clear in her deft handling of the folds of skin and the strength of passion she feels, that never moves into eroticism. Gentileschi brings a private movement with God into the public, and does so in a way that feels relatable, familiar to us the viewer, thus encouraging us to lose ourselves in ecstasy with a higher power.

Summer Night

WINSLOW HOMER

In England, after a decade of painting scenes of American idyll, Homer lost his innocence. The spontaneous, bright, and almost doll house quality of his early work, one preoccupied with a vision of his country and its beauty, dissipated and in its place came something more universal, touching a higher plane. It was this return from his 2 years away, that he moved to a small house some seventy feet from the sea in Maine and his subject matter became informed by the swell, the danger and the shimmering beauty of the water that he saw from his window each day. ‘Summer Night’ is a study of restraint, revealing just enough to create a sense of longing, but not so much that we can’t see ourselves in the scene. The soft focus of two dancers, watched by a group in shadows as the light glistens from the stormy sea behind them, captures a poignant romance that each of us can understand.

Winslow Homer

SUMMER NIGHT, 1890. OIL ON CANVAS.

In England, after a decade of painting scenes of American idyll, Homer lost his innocence. The spontaneous, bright, and almost doll house quality of his early work, one preoccupied with a vision of his country and its beauty, dissipated and in its place came something more universal, touching a higher plane. It was this return from his 2 years away, that he moved to a small house some seventy feet from the sea in Maine and his subject matter became informed by the swell, the danger and the shimmering beauty of the water that he saw from his window each day. ‘Summer Night’ is a study of restraint, revealing just enough to create a sense of longing, but not so much that we can’t see ourselves in the scene. The soft focus of two dancers, watched by a group in shadows as the light glistens from the stormy sea behind them, captures a poignant romance that each of us can understand.

Mojave

ARSHILE GORKY

An Armenian refugee, escaping the genocide, who took on the name of Georgian nobility and became one of America’s most influential and important painters, Gorky remains to this day enigmatic and illusive. Though his work does not immediately appear of the genre, Gorky was the spiritual founder of Abstract Expressionism. Andre Breton tried to claim him as a surrealist and the Paris School and New York School of Artists both consider Gorky a profound influence. His work is lyrically abstract, using biomorphic forms that simultaneously express pure emotion, transferred from mind to hand with no interference from the conscious, while being unplaceably figurative. He was a bridge between languages, inspiring the visual linguists who came after him and changing the way his contemporaries thought. More than just bridging movements, Gorky was a connection between European and American art worlds, fostering trans-Atlantic relationships that shrunk the world around him into a unified, collaborative place.

Arshile Gorky

ARSHILE GORKY, 1941. OIL ON CANVAS.

An Armenian refugee, escaping the genocide, who took on the name of Georgian nobility and became one of America’s most influential and important painters, Gorky remains to this day enigmatic and illusive. Though his work does not immediately appear of the genre, Gorky was the spiritual founder of Abstract Expressionism. Andre Breton tried to claim him as a surrealist and the Paris School and New York School of Artists both consider Gorky a profound influence. His work is lyrically abstract, using biomorphic forms that simultaneously express pure emotion, transferred from mind to hand with no interference from the conscious, while being unplaceably figurative. He was a bridge between languages, inspiring the visual linguists who came after him and changing the way his contemporaries thought. More than just bridging movements, Gorky was a connection between European and American art worlds, fostering trans-Atlantic relationships that shrunk the world around him into a unified, collaborative place.

Woman Reading

JOHN STORRS

A new age had begun, one filled with technological wonders, hope and optimism. Yet but 1949, this had waned in the shadow of the war, and the open fields of potential seemed to yield less than they had promised. The human imagination that had so expanded at the turn of the century had been corrupted, and the artists who had first seized upon modernity, it seemed, had paid too much reverence to the bright future they saw ahead. Storrs was one such artist, having been part of the culture epoch in Paris that helped fuel the revolution in the new visual language. Yet his later work, like Woman Reading, addresses some of the naivety of his youth and the worship of the experienced world that had gone with it. Here, referential ties are still present, the figure and the setting are clear, but it has been reduced to simplicity, to something more formal and abstract that speaks to a universal detachment as much as it does his personal expression. Storr’s work grew with him, and it’s in subtle cues, showed the changing optimism of a new century becoming old.

John Storrs

JOHN STORRS, 1949. OIL ON CANVAS.

A new age had begun, one filled with technological wonders, hope and optimism. Yet but 1949, this had waned in the shadow of the war, and the open fields of potential seemed to yield less than they had promised. The human imagination that had so expanded at the turn of the century had been corrupted, and the artists who had first seized upon modernity, it seemed, had paid too much reverence to the bright future they saw ahead. Storrs was one such artist, having been part of the culture epoch in Paris that helped fuel the revolution in the new visual language. Yet his later work, like Woman Reading, addresses some of the naivety of his youth and the worship of the experienced world that had gone with it. Here, referential ties are still present, the figure and the setting are clear, but it has been reduced to simplicity, to something more formal and abstract that speaks to a universal detachment as much as it does his personal expression. Storr’s work grew with him, and it’s in subtle cues, showed the changing optimism of a new century becoming old.

Actual Size

ED RUSCHA

Words, humour, and the great American iconography are the three themes that underpin so much of Ruscha’s work. Actual Size is a perfect synthesis of these ideas in this period, operating on multiple levels as both an artwork and a visual joke. Painted the same year that Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans were shown, it was part of a new movement in art that co-opted the insignia and objects of American Life and elevated them into art forms. Yet Ruscha went one step further than Warhol – rather than simply depicting the product and its wordmark, he took inspiration from Chuck Yeager, an early astronaut and flying ace, who described took issue with the new, heavily automated spaceships that reduced their pilots to simple being ‘Spam in a Can’. Ruscha’s Spam takes flight, leaving a streak behind it as it soars across the white field. This is a monumental work that brings us in and out of context, recontextualising the word and the product while also serving as an ode to the great American processed meat.

Ed Ruscha

ED RUSHCA, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS.

Words, humour, and the great American iconography are the three themes that underpin so much of Ruscha’s work. Actual Size is a perfect synthesis of these ideas in this period, operating on multiple levels as both an artwork and a visual joke. Painted the same year that Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans were shown, it was part of a new movement in art that co-opted the insignia and objects of American Life and elevated them into art forms. Yet Ruscha went one step further than Warhol – rather than simply depicting the product and its wordmark, he took inspiration from Chuck Yeager, an early astronaut and flying ace, who described took issue with the new, heavily automated spaceships that reduced their pilots to simple being ‘Spam in a Can’. Ruscha’s Spam takes flight, leaving a streak behind it as it soars across the white field. This is a monumental work that brings us in and out of context, recontextualising the word and the product while also serving as an ode to the great American processed meat.

St. Jerome

EL GRECO

El Greco returned five times to the image of Saint Jerome, depicting him in various states and guises. Jerome was a priest, theologian, historian and translator who produced the most important Latin translation of the bible. This representation is amongst El Greco’s later of Jerome, and shows him primarily as a scholar, in sumptuous velvet garb with vividly emphasised folds, pointing at the bible with authority. Though Greco depicted him earlier as a penitent, he retains some of the same features in this painting of him as a scholar. The long white beard and gaunt features allude to his time spent in the Syrian desert, contrasted with his clothes and elevated status here. The work is about Jerome’s duality, showing his life story in but a single frame, one that captures his importance, achievements and status while making clear the hardships he has been through.

El Greco

EL GRECO, c.1610. OIL ON CANVAS.

El Greco returned five times to the image of Saint Jerome, depicting him in various states and guises. Jerome was a priest, theologian, historian and translator who produced the most important Latin translation of the bible. This representation is amongst El Greco’s later of Jerome, and shows him primarily as a scholar, in sumptuous velvet garb with vividly emphasised folds, pointing at the bible with authority. Though Greco depicted him earlier as a penitent, he retains some of the same features in this painting of him as a scholar. The long white beard and gaunt features allude to his time spent in the Syrian desert, contrasted with his clothes and elevated status here. The work is about Jerome’s duality, showing his life story in but a single frame, one that captures his importance, achievements and status while making clear the hardships he has been through.

Black and White Number 20

JACKSON POLLOCK

In furious movement and palpable energy, a new dawn broke. Pollock was the figurehead and the engine behind a new conception and understanding of art, one that built on Surrealist ideas of unconscious drawing, where the hand was allowed to move freely, unchained from the ideas of the waking mind, but pushed it further to truly represent emotion. Called Abstract Expressionism, it removed not only conscious thought from the creation of artworks but, in Pollocks case, interaction between the hand and the canvas. Pollock would stand above the blank page and splatter paint in wild gestures, allowing the chaos of the natural, physical world to serve as his collaborator. The work is visceral and immediate, for all its abstraction it provides a clearer representation of the psyche than any works that came before. Black and White Number 20 was made just 5 years before Pollocks untimely death and at a time when his alcoholism was worsening. It feature little brushwork, but is more deliberate than earlier examples, the monochromatic nature not allowing us to get lost in anything other than the texture and Rorschach form.

Jackson Pollock

JACKSON POLLOCK, 1951. OIL ON CANVAS.

In furious movement and palpable energy, a new dawn broke. Pollock was the figurehead and the engine behind a new conception and understanding of art, one that built on Surrealist ideas of unconscious drawing, where the hand was allowed to move freely, unchained from the ideas of the waking mind, but pushed it further to truly represent emotion. Called Abstract Expressionism, it removed not only conscious thought from the creation of artworks but, in Pollocks case, interaction between the hand and the canvas. Pollock would stand above the blank page and splatter paint in wild gestures, allowing the chaos of the natural, physical world to serve as his collaborator. The work is visceral and immediate, for all its abstraction it provides a clearer representation of the psyche than any works that came before. Black and White Number 20 was made just 5 years before Pollocks untimely death and at a time when his alcoholism was worsening. It feature little brushwork, but is more deliberate than earlier examples, the monochromatic nature not allowing us to get lost in anything other than the texture and Rorschach form.

Winter Hunt

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Is color more important than gesture in art? This was the question Helen Frankenthaler was addressing and for her, the answer was clear. Pioneering a ‘soak-stain’ technique, she would pour paint directly onto untreated canvases and let it sink into the fabric, leaving behind vibrant and uncontrolled stains. This was in stark opposition to her male Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, Jackson Pollock amongst them, who used violent brushstrokes and expressive gesture in their works. Frankenthaler was part of a group of female artists that included Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, and Joan Mitchell, who’s works speak to a natural beauty, emphasising the palette that existed around them, rather than trying to create something alien. In Winter Hunt, an empty top half emphasises the interplay of the palette below, allowing the beauty of the rich stains to stand out. Though the human hand is not obvious, the drops and swirls clearly from a pouring technique, there is harmony to the work that is unmistakably human, albeit one in touch with the world around them.

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN FRANKENTHALER, 1958. OIL ON CANVAS.

Is color more important than gesture in art? This was the question Frankenthaler was addressing and for her, the answer was clear. Pioneering a ‘soak-stain’ technique, she would pour paint directly onto untreated canvases and let it sink into the fabric, leaving behind vibrant and uncontrolled stains. This was in stark opposition to her male Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, Jackson Pollock amongst them, who used violent brushstrokes and expressive gesture in their works. Frankenthaler was part of a group of female artists that included Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, and Joan Mitchell, who’s works speak to a natural beauty, emphasising the palette that existed around them, rather than trying to create something alien. In Winter Hunt, an empty top half emphasises the interplay of the palette below, allowing the beauty of the rich stains to stand out. Though the human hand is not obvious, the drops and swirls clearly from a pouring technique, there is harmony to the work that is unmistakably human, albeit one in touch with the world around them.

The Transparent Woman

GORDON ONSLOW FORD

Gordon Onslow Ford was the last of his kind – the final surviving surrealist who saw the world change in the image he had helped imagine. One of the few significant members of Breton’s group of surrealists and amongst the only native English speak, Onslow Ford abandoned a regimented and expected career in the Navy to live in Paris and fulfil his passion and purpose. Regularly attending the movements exclusive meetings at Cafè deux Magots in Paris, he ingratiated himself with every important member of the group, hosting them for summers at a chateau near Switzerland. Yet of all the group, it was his friendship with the architect Roberto Matta that most informed his work. Together, they studied the mathematical and the metaphysical, and from Matta’s architectural drawings he learned his own understanding of perspective. He combined the cosmic and the rational, bringing mystic and surrealist ideas into a mathematical framework to speak to an ordered chaos of reality.

Gordon Onslow Ford

GORDON ONSLOW FORD, c.1940. OIL ON CANVAS.

Gordon Onslow Ford was the last of his kind – the final surviving surrealist who saw the world change in the image he had helped imagine. One of the few significant members of Breton’s group of surrealists and amongst the only native English speak, Onslow Ford abandoned a regimented and expected career in the Navy to live in Paris and fulfil his passion and purpose. Regularly attending the movements exclusive meetings at Cafè deux Magots in Paris, he ingratiated himself with every important member of the group, hosting them for summers at a chateau near Switzerland. Yet of all the group, it was his friendship with the architect Roberto Matta that most informed his work. Together, they studied the mathematical and the metaphysical, and from Matta’s architectural drawings he learned his own understanding of perspective. He combined the cosmic and the rational, bringing mystic and surrealist ideas into a mathematical framework to speak to an ordered chaos of reality.

Anthropometrie

KLEIN

Klein replaced the paintbrush with the body. Working in collaboration with models covered in his signature blue paint, he instructed and directed them to push themselves against canvas and paper to leave remnants, ghostly leftovers, of their own form. This was a radical and controversial movement, not only for the perceived lewdness of the process, but because it took art our of the frame and placed it into everyday surroundings. It guided a passage from the material to the immaterial realm, beckoning in a transcendent idea of art that Klein believed in, one where the gulf between the human and the heavenly disappeared. On a visit to Hiroshima, Klein saw the impression of a man seared into stone, the mark of pain and destruction integrated man into the eternal nature that surrounded him. With more joy, freedom and intention, Klein was attempting the same with his Anthropometrie series. Bodies, flesh, and humans are mortal and transient, but we can coalesce with nature to rise above our mortality and reach the divine.

Yves Klein

YVES KLEIN, 1962. OIL ON PAPER.

Yves Klein replaced the paintbrush with the body. Working in collaboration with models covered in his signature blue paint, he instructed and directed them to push themselves against canvas and paper to leave remnants, ghostly leftovers, of their own form. This was a radical and controversial movement, not only for the perceived lewdness of the process, but because it took art out of the frame and placed it into everyday surroundings. It guided a passage from the material to the immaterial realm, beckoning in a transcendent idea of art that Klein believed in, one where the gulf between the human and the heavenly disappeared. On a visit to Hiroshima, Klein saw the impression of a man seared into stone, the mark of pain and destruction integrated man into the eternal nature that surrounded him. With more joy, freedom and intention, Klein was attempting the same with his Anthropometrie series. Bodies, flesh, and humans are mortal and transient, but we can coalesce with nature to rise above our mortality and reach the divine.

The Resurrection

BOTTICINI

Botticini, for all of his genius, is historically illusive. We have very few works confirmed to be by his hand, but many more which have since been attributed to him with some certainty, though without the necessary records to be definitive. His handiwork exists as invisible threads pulled by art historians, finding fingerprints of a master, and contemporary of Da Vinci, in works long mis-authored. Born in Florence as the impact of the Renaissance was growing, his father made and painted playing cards and trained the young Francisco in his early life, before he joined Leonardo Da Vince as an apprentice in the workshop of Del Verrocchio. Botticini’s work was unusual, graphic and compositional strange, perhaps inspired by the playing cards he grew up painting. The work, despite obvious technical signs of age, feels extraordinarily contemporary, the manipulation of planes and positioning of Jesus is almost surrealist. It is a celebratory, affecting and uncanny work of reverence and experimentation.

Francesco Botticini

FRANCESCO BOTTICINI, c.1467. TEMPERA ON POPLAR.

Botticini, for all of his genius, is historically illusive. We have very few works confirmed to be by his hand, but many more which have since been attributed to him with some certainty, though without the necessary records to be definitive. His handiwork exists as invisible threads pulled by art historians, finding fingerprints of a master, and contemporary of Da Vinci, in works long mis-authored. Born in Florence as the impact of the Renaissance was growing, his father made and painted playing cards and trained the young Francisco in his early life, before he joined Leonardo Da Vince as an apprentice in the workshop of Del Verrocchio. Botticini’s work was unusual, graphic and compositional strange, perhaps inspired by the playing cards he grew up painting. The work, despite obvious technical signs of age, feels extraordinarily contemporary, the manipulation of planes and positioning of Jesus is almost surrealist. It is a celebratory, affecting and uncanny work of reverence and experimentation.