Apache Dancer

FRANZ KLINE

Franz Kline was a painter of his own life. He reflected the cultural milieu that surrounded him, and as he moved from figurative work to abstract expression his work never lost a personal representation. In 1940, after years working as a struggling artist in New York’s Greenwich Village, Kline was commissioned by the owner of Bleeker Street Tavern to create a series of ten murals to decorate the watering hole. He was paid five dollars apiece, and the works depict a night at the burlesque show, as requested by the proprietor in an attempt to attract male clientele to his bar. Yet Kline eschewed tradition and expectation, rejecting the graphic work that was standard for such commissions in favour of something altogether more emotional and personal. Kline’s murals mark a bridge in artistic history, the dawn of abstract expressionist work, his loose lines and brushstrokes marking things to come. He imbues his paintings with emotional depth that far exceeded commercial murals of the day, capturing the spirit not just of the burlesque entertainment but of the nation as a whole.

Frank Kline

FRANZ KLINE, 1940. OIL ON CANVAS BOARD.

Franz Kline was a painter of his own life. He reflected the cultural milieu that surrounded him, and as he moved from figurative work to abstract expression his work never lost a personal representation. In 1940, after years working as a struggling artist in New York’s Greenwich Village, Kline was commissioned by the owner of Bleeker Street Tavern to create a series of ten murals to decorate the watering hole. He was paid five dollars apiece, and the works depict a night at the burlesque show, as requested by the proprietor in an attempt to attract male clientele to his bar. Yet Kline eschewed tradition and expectation, rejecting the graphic work that was standard for such commissions in favour of something altogether more emotional and personal. Kline’s murals mark a bridge in artistic history, the dawn of abstract expressionist work, his loose lines and brushstrokes marking things to come. He imbues his paintings with emotional depth that far exceeded commercial murals of the day, capturing the spirit not just of the burlesque entertainment but of the nation as a whole.

The Arrival

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO

Everyday reality crashes into surrealist mythology as perspectives warp and time flattens into a single, unknowable, unplaceable landscape. After a revelation in a Florence piazza, De Chicoro began to paint obsessively, trying to capture the uncanny feelings that could not be translated into anything but painting, allowing for his personal sensitivity to the strangeness of the human environment to create metaphysical works. The works are paradoxical, evoking a feeling of nostalgia as well as novelty, empty, forlorn and hopeless they nonetheless convey a sense of power and freedom. De Chirico condensed the enormity of feeling, the bombardment of daily life into metaphor – inspired by the writing of Friedrich Nietzsche, he tried to capture the ominous existence beneath the surface of writing in oil paint. Predating the surrealists, his work established a foundation for warped perspective of existence to speak more truthfully than any attempts at representation ever could.

Giorgio de Chirico

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO, 1913. OIL ON CANVAS.

Everyday reality crashes into surrealist mythology as perspectives warp and time flattens into a single, unknowable, unplaceable landscape. After a revelation in a Florence piazza, De Chicoro began to paint obsessively, trying to capture the uncanny feelings that could not be translated into anything but painting, allowing for his personal sensitivity to the strangeness of the human environment to create metaphysical works. The works are paradoxical, evoking a feeling of nostalgia as well as novelty, empty, forlorn and hopeless they nonetheless convey a sense of power and freedom. De Chirico condensed the enormity of feeling, the bombardment of daily life into metaphor – inspired by the writing of Friedrich Nietzsche, he tried to capture the ominous existence beneath the surface of writing in oil paint. Predating the surrealists, his work established a foundation for warped perspective of existence to speak more truthfully than any attempts at representation ever could.

Dionysius

BARNETT NEWMAN

Long before he completed a painting he deemed worthy of public view, in 1933 Barnett Newman ran as a candidate for the Mayor of New York. Working a substitute teacher at the time, his campaign was based on the simple maxim that ‘only a society entirely composed of artists would be really worth living in'. It is unclear how many, if any, votes Newman got, and his political career ended with that election, but his vision for society remained with him forever. It would be nearly fifteen years before his artistic awakening with the development of his Onement series, a third way of painting that comprised of a single vertical line against a deep field of colour. Newman’s work, his new technique and idea of painting was primal, and in its primacy it was so accessible that anyone could understand it, if not create it themselves – he was creating in his work the possibility of a society filled with artists.

Barnett Newman

BARNETT NEWMAN, 1949. OIL ON CANVAS.

Long before he completed a painting he deemed worthy of public view, in 1933 Barnett Newman ran as a candidate for the Mayor of New York. Working a substitute teacher at the time, his campaign was based on the simple maxim that ‘only a society entirely composed of artists would be really worth living in'. It is unclear how many, if any, votes Newman got, and his political career ended with that election, but his vision for society remained with him forever. It would be nearly fifteen years before his artistic awakening with the development of his Onement series, a third way of painting that comprised of a single vertical line against a deep field of colour. Newman’s work, his new technique and idea of painting was primal, and in its primacy it was so accessible that anyone could understand it, if not create it themselves – he was creating in his work the possibility of a society filled with artists.

Untitled (String Quartet)

MARK ROTHKO

To think of Mark Rothko is to think of colour fields. Imposing canvases of thick paint, dark hues that engulf in a pure abstraction, ominous and potent in their scale, their simplicity and their size. Yet Rothko only came to these definitive works when he was well into his forties. For his early period, he created impressionist, representational works depicting urban scenes in small vignettes, as with the Quartet here. It is thrilling to see an artist working outside of their signatures, for hiding within Rothko’s painting are clues for what is to come. He tried, in this period, to paint as a child; inspired by ‘primitive art’, he saw a relationship between artistic works of early civilization and the naivety of a child’s representation of their world. Even in these early representational works, we can see a mastery of colour as a tool for emotion, the deep browns and greys are menacing and there is a sense of imposition across the work. Remove the string players and the background could be a work from 20 years later in his maturity. To see Rothko’s early work is to see an artist stripping back to purity, grappling with the same themes and emotions but distilling them down to their most powerful form.

Mark Rothko

MARK ROTHKO, 1935. OIL ON HARDBOARD.

To think of Mark Rothko is to think of colour fields. Imposing canvases of thick paint, dark hues that engulf in a pure abstraction, ominous and potent in their scale, their simplicity and their size. Yet Rothko only came to these definitive works when he was well into his forties. For his early period, he created impressionist, representational works depicting urban scenes in small vignettes, as with the Quartet here. It is thrilling to see an artist working outside of their signatures, for hiding within Rothko’s painting are clues for what is to come. He tried, in this period, to paint as a child; inspired by ‘primitive art’, he saw a relationship between artistic works of early civilization and the naivety of a child’s representation of their world. Even in these early representational works, we can see a mastery of colour as a tool for emotion, the deep browns and greys are menacing and there is a sense of imposition across the work. Remove the string players and the background could be a work from 20 years later in his maturity. To see Rothko’s early work is to see an artist stripping back to purity, grappling with the same themes and emotions but distilling them down to their most powerful form.

Homage to the Square

JOSEF ALBERS

Four squares of paint, applied to cheap pressed wood, directly from the tube. Josef Alber’s homages lasted for more than 25 years from 1950 to his death in 1976, occupying his mind obsessively. Having been a professor at the Bauhaus, he moved to America and taught at both Yale and Black Mountain College, there honing his framework and establishing a new vernacular of colour and form that would go on to define the 20th century. From the narrowest conceptual frameworks can the most extraordinary perceptual complexity arise. The ‘Homage to the Square’ went on to number more than 2,000 paintings, created sequentially. Singularly fascinated with the interaction of colour, each successive variation on Albers' basic compositional scheme brought new adjustments in hue, tone and intensity. His 1963 book ‘Interaction of Colour’ referred to such experiments as ‘a study of ourselves’. What at first glance would appear to be ‘just’ four squares belies Albers' true depth - that of chromatic harmony.

Josef Albers

JOSEF ALBERS, 1957. CASEIN AND OIL ON MASONITE

Four squares of paint, applied to cheap pressed wood, directly from the tube. Josef Alber’s homages lasted for more than 25 years from 1950 to his death in 1976, occupying his mind obsessively. Having been a professor at the Bauhaus, he moved to America and taught at both Yale and Black Mountain College, there honing his framework and establishing a new vernacular of colour and form that would go on to define the 20th century. From the narrowest conceptual frameworks can the most extraordinary perceptual complexity arise. The ‘Homage to the Square’ went on to number more than 2,000 paintings, created sequentially. Singularly fascinated with the interaction of colour, each successive variation on Albers' basic compositional scheme brought new adjustments in hue, tone and intensity. His 1963 book ‘Interaction of Colour’ referred to such experiments as ‘a study of ourselves’. What at first glance would appear to be ‘just’ four squares belies Albers' true depth - that of chromatic harmony.

The Assumption of the Virgin

PETER PAUL RUBENS

The Virgin Mary is a font of true light as she is assumed, meaning to ‘raise up’, into the heavens, accompanied by a multitude angels. At her feet, 12 apostles, Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary’s two sisters are bathed in her divinity and her beauty. Ruben’s interpreted this story in his own way, seeing her ascension as analogous to the rising of the sun, as her purity and divinity is often talked about as a source of light. So Mary becomes the sun, the knot of angels that surround her bleed in and out of the clouds that they become. It is a work of reverence and praise, but from a distance it could be easily misinterpreted as a landscape. This duality was intentional not just as a compositional allegory but as an audition. This work was a presentation sketch for a larger painted version of the high altar of Antwerp Cathedral, and Rubens employed every tool in his arsenal to show his mastery and secure the job.

Peter Paul Rubens

PETER PAUL RUBENS, c.1612. OIL ON PANEL.

The Virgin Mary is a font of true light as she is assumed, meaning to ‘raise up’, into the heavens, accompanied by a multitude angels. At her feet, 12 apostles, Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary’s two sisters are bathed in her divinity and her beauty. Ruben’s interpreted this story in his own way, seeing her ascension as analogous to the rising of the sun, as her purity and divinity is often talked about as a source of light. So Mary becomes the sun, the knot of angels that surround her bleed in and out of the clouds that they become. It is a work of reverence and praise, but from a distance it could be easily misinterpreted as a landscape. This duality was intentional not just as a compositional allegory but as an audition. This work was a presentation sketch for a larger painted version of the high altar of Antwerp Cathedral, and Rubens employed every tool in his arsenal to show his mastery and secure the job.

Lake George

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

For 16 years, Georgia O’Keefe left the desert and the city behind and spent her springtimes in the Adirondacks. Immersed in solitude and nature, her works softened through long walks and quiet meditation, looking out over Lake George. Pastoral, full of life and idyllic, O’Keefe fought her own rebellion to fall in love with the landscape. More known for her paintings of the desert, of yonic flowers and floating skulls, the works at Lake George are a departure of sorts. Read as an abstract work, this painting is a masterpiece of form and colour, the undulating mountains blurring into their own reflection to become a single unified motion. The soft hues that invite us into the canvas are removed the real world she was observing. In many ways, the New York countryside was too picture-postcard for O’Keefe, so her paintings reduce it to something all the more strange, peaceful and serene, with a sense of disquiet throughout. ‘There is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees’, she said, ‘sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces’.

Georgia O’Keeffe

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE, 1922. OIL ON CANVAS.

For 16 years, Georgia O’Keeffe left the desert and the city behind and spent her springtimes in the Adirondacks. Immersed in solitude and nature, her works softened through long walks and quiet meditation, looking out over Lake George. Pastoral, full of life and idyllic, O’Keeffe fought her own rebellion to fall in love with the landscape. More known for her paintings of the desert, of yonic flowers and floating skulls, the works at Lake George are a departure of sorts. Read as an abstract work, this painting is a masterpiece of form and colour, the undulating mountains blurring into their own reflection to become a single unified motion. The soft hues that invite us into the canvas are removed the real world she was observing. In many ways, the New York countryside was too picture-postcard for O’Keeffe, so her paintings reduce it to something all the more strange, peaceful and serene, with a sense of disquiet throughout. ‘There is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees’, she said, ‘sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces’.

Esther and Mordecai

HENDRICK VAN STEENWIJK

How does a painting sound? Looking at Esther and Mordecai, the sonics are clear. Hushed tones bounce off stone walls, the whispers seem to travel through the corridor and out of the canvas. Hendrick van Steenwijk the Younger, a master of the early Flemish Baroque, activates every sense with his brushstrokes. Predominantly a painter of Architectural scenes, Van Steenwijk would include narrative vignettes within the worlds he portrayed, often snippets from biblical fables. In this way, he flattened time, depicting antiquity within his contemporary worlds and bringing faith into a recognisable modernity. His paintings are visceral; in the case of Esther and Mordecai we can feel the painting, the cold stone sends shivers, the hushed tones flutter to our ears and the musk of an ancient hallway fills our noses. Van Steenwijk was an alchemist who turned oil and wood into tangible, sensory worlds and shortened the length between centuries.

Hendrick van Stenwijk the Younger

HENDRICK VAN STEENWIJK THE YOUNGER, 1616. OIL ON PANEL.

How does a painting sound? Looking at Esther and Mordecai, the sonics are clear. Hushed tones bounce off stone walls, the whispers seem to travel through the corridor and out of the canvas. Hendrick van Steenwijk the Younger, a master of the early Flemish Baroque, activates every sense with his brushstrokes. Predominantly a painter of Architectural scenes, Van Steenwijk would include narrative vignettes within the worlds he portrayed, often snippets from biblical fables. In this way, he flattened time, depicting antiquity within his contemporary worlds and bringing faith into a recognisable modernity. His paintings are visceral; in the case of Esther and Mordecai we can feel the painting, the cold stone sends shivers, the hushed tones flutter to our ears and the musk of an ancient hallway fills our noses. Van Steenwijk was an alchemist who turned oil and wood into tangible, sensory worlds and shortened the length between centuries.

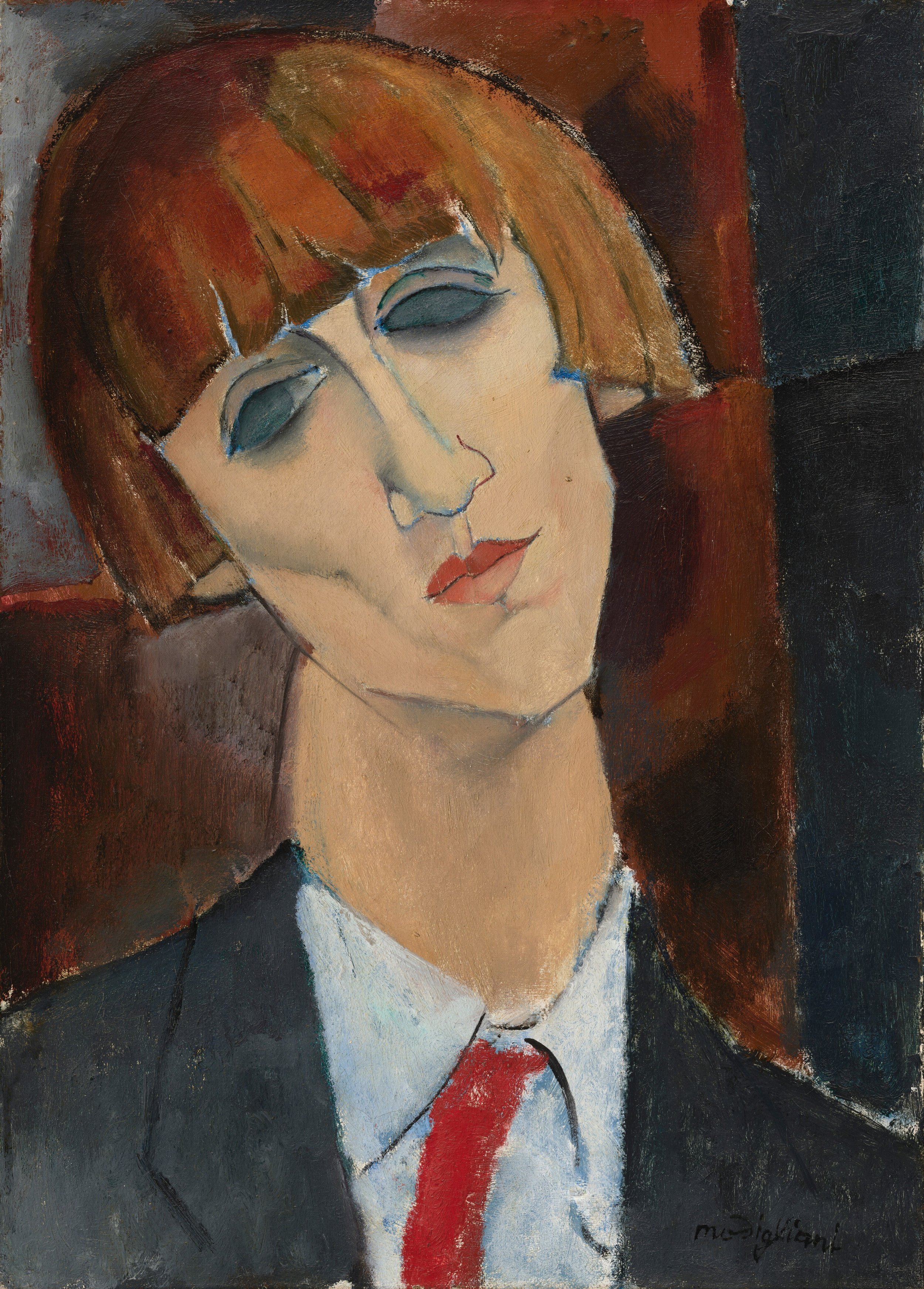

Madame Kisling

AMADEO MODIGLIANI

Modigliani is most famous for his female nudes, their elongated, distorted bodies are soft and fluid, his characteristic almond eyes make their faces almost mask like. Since Modigliani began painting, his figures have been the essence of modernity. Yet, they lived within a traditional of nude painting and portraiture, and while they subverted that tradition, they still existed within in. Here, in his portrait of his protégé Moise Kisling’s wife Renee Kisling, he epitomises modernity. She is dressed in the cutting edge vogue of the day, wearing men’s suiting and short thick hair. Modigliani traditionally curve lines give way here to sharp angles, gone are the undulations of almond shaped faces and in their place a decisive, almost aggressive bone structure quite unlike any of his other portraits, combining feminine strength and sensuality. Madame Kisling is an exception in Modigliani’s oeuvre, and his portrait of her cemented a changing of the tide as aesthetic modernity across mediums met in harmony.

Amedeo Modigliani

AMEDEO MODIGLIANI, c1917. OIL ON CANVAS

Modigliani is most famous for his female nudes, their elongated, distorted bodies are soft and fluid, his characteristic almond eyes make their faces almost mask like. Since Modigliani began painting, his figures have been the essence of modernity. Yet, they lived within a traditional of nude painting and portraiture, and while they subverted that tradition, they still existed within in. Here, in his portrait of his protégé Moise Kisling’s wife Renee Kisling, he epitomises modernity. She is dressed in the cutting edge vogue of the day, wearing men’s suiting and short thick hair. Modigliani traditionally curve lines give way here to sharp angles, gone are the undulations of almond shaped faces and in their place a decisive, almost aggressive bone structure quite unlike any of his other portraits, combining feminine strength and sensuality. Madame Kisling is an exception in Modigliani’s oeuvre, and his portrait of her cemented a changing of the tide as aesthetic modernity across mediums met in harmony.

The Basket

RAOUL DUFY

Raoul Dufy was torn between two instincts. In 1905, he saw Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté and was immediately drawn towards Fauvism, becoming part of the circle of artists that included Matisse and Cezanne. Yet Dufy’s natural skill was as a draughtsman and he was a master of fine lines and detail, something quite counter to the ethos of Fauvism’s wild colours and impressionistic contours. His illustrator nature and fauvist ideals collided with glorious results, a tension clear in his work between two styles produced subtle and evocative paintings. The wild beast of fauvism was in some way tamed under Dufy, who’s fruitful contradiction produced work across mediums, from textile pattern and stationary design to city planning and scenic design. All of these disciplines informed his painting, where he used a technical ability and deep understanding of space to create pieces that seem at once totally real and wholly grounded in the imagination.

Raoul Dufy

RAOUL DUFY, 1926. OIL ON CANVAS.

Raoul Dufy was torn between two instincts. In 1905, he saw Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté and was immediately drawn towards Fauvism, becoming part of the circle of artists that included Matisse and Cezanne. Yet Dufy’s natural skill was as a draughtsman and he was a master of fine lines and detail, something quite counter to the ethos of Fauvism’s wild colours and impressionistic contours. His illustrator nature and fauvist ideals collided with glorious results, a tension clear in his work between two styles produced subtle and evocative paintings. The wild beast of fauvism was in some way tamed under Dufy, who’s fruitful contradiction produced work across mediums, from textile pattern and stationary design to city planning and scenic design. All of these disciplines informed his painting, where he used a technical ability and deep understanding of space to create pieces that seem at once totally real and wholly grounded in the imagination.

Moonlight

GEORGE MATSUSABURO HIBI

In 1942, after more than 30 years living in the United States and working as an artist in a burgeoning Californian scene, George Matsusaburo Hibi was interned in an American concentration camp under the order of FDR. Hibi was not threat to America, but he was not a naturalised citizen and so, as tensions between USA and Japan were rising, he became one of thousands of victims of Order 9066. At the age of 20, inspired by Cezanne, Hibi had given up his legal studies in Japan and moved to the American west coast where he successfully pursued an artistic career. He showed across California, organising shows at the SF Museum of Art and setting up a society of East Asian artists living on the West Coast. Hibi was dedicated to the power of art as a unifying force, and even during his time in the internment camps, he set up art schools and organised exhibitions and classes. In 1940, when the threat of war was imminent, he began to donate paintings to community venues across California. ‘There is no boundary in art.’, he said, ‘This is the only way I can show my appreciation to my many American friends here.’

George Matsusaburo Hibi

GEORGE MATSUSABURO HIBI, 1945. WOODCUT ON PAPER.

In 1942, after more than 30 years living in the United States and working as an artist in a burgeoning Californian scene, George Matsusaburo Hibi was interned in an American concentration camp under the order of FDR. Hibi was not threat to America, but he was not a naturalised citizen and so, as tensions between USA and Japan were rising, he became one of thousands of victims of Order 9066. At the age of 20, inspired by Cezanne, Hibi had given up his legal studies in Japan and moved to the American west coast where he successfully pursued an artistic career. He showed across California, organising shows at the SF Museum of Art and setting up a society of East Asian artists living on the West Coast. Hibi was dedicated to the power of art as a unifying force, and even during his time in the internment camps, he set up art schools and organised exhibitions and classes. In 1940, when the threat of war was imminent, he began to donate paintings to community venues across California. ‘There is no boundary in art.’, he said, ‘This is the only way I can show my appreciation to my many American friends here.’

The Angelus

JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET

The Angelus took on spiritual and religious significance far beyond its painter’s intentions. It spawned a patriotic fervour when it nearly left France, inspired a madman to attack it with a knife, became an obsession of Salvador Dali, spawned an artistic revolution that informed Van Gogh, Matisse, Seurat and Cezanne and is well regarded as one of the greatest religious works of all time. All of this for a work of tranquil reverence, made from nostalgia Millet felt towards his grandmother. It depicts two labourers, upon hearing the church bell toll for the end of the day, in quiet prayer. Millet did not paint it as a religious work, yet he captured the essence of faith, of the serenity of devotion across society. It is not grand nor biblical, but honest and humble, truer to religious values that so many works of splendour. The significance of The Angelus comes from its depiction of the seemingly insignificant.

Jean-François Millet

JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET, 1859. OIL ON CANVAS.

The Angelus took on spiritual and religious significance far beyond its painter’s intentions. It spawned a patriotic fervour when it nearly left France, inspired a madman to attack it with a knife, became an obsession of Salvador Dali, spawned an artistic revolution that informed Van Gogh, Matisse, Seurat and Cezanne and is well regarded as one of the greatest religious works of all time. All of this for a work of tranquil reverence, made from nostalgia Millet felt towards his grandmother. It depicts two labourers, upon hearing the church bell toll for the end of the day, in quiet prayer. Millet did not paint it as a religious work, yet he captured the essence of faith, of the serenity of devotion across society. It is not grand nor biblical, but honest and humble, truer to religious values that so many works of splendour. The significance of The Angelus comes from its depiction of the seemingly insignificant.

Terracotta Pots and Flowers

PAUL CÉZANNE

In the cold Parisian winters, Cézanne would paint in the greenhouse to keep warm. His studio was filled with assorted objects that he drew upon when needed, creating endless combinations from a small and simple repertoire in which to craft his still lives. An austere water pitcher, an old rum bottle with straw bindings, a tattered red cloth - household objects which when placed against the plants in the greenhouse become works of contemplative beauty. Cézanne’s still lives can be understood as partial portraits of himself, revealing not only in the explicit clues they give us about his residence or living situation, but in the implicit form of the objects. The way leaves on the plants fall, the plumpness of the petals, the drape of the cloth; Cézanne was rigorous and particular about what he painted and when, and there are clues as to his state of mind in each brushstroke. When this works as painted, the artist was retreating from his impressionist contemporaries, and struggling with ill-health in the winter months. There is hopefulness in the plant life depicted, but a coolness of light pervades as if with the ambiguity of a future.

Paul Cézanne

PAUL CEZANNE, c.1892. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the cold Parisian winters, Cézanne would paint in the greenhouse to keep warm. His studio was filled with assorted objects that he drew upon when needed, creating endless combinations from a small and simple repertoire in which to craft his still lives. An austere water pitcher, an old rum bottle with straw bindings, a tattered red cloth - household objects which when placed against the plants in the greenhouse become works of contemplative beauty. Cézanne’s still lives can be understood as partial portraits of himself, revealing not only in the explicit clues they give us about his residence or living situation, but in the implicit form of the objects. The way leaves on the plants fall, the plumpness of the petals, the drape of the cloth; Cézanne was rigorous and particular about what he painted and when, and there are clues as to his state of mind in each brushstroke. When this work was painted, the artist was retreating from his impressionist contemporaries, and struggling with ill-health in the winter months. There is hopefulness in the plant life depicted, but a coolness of light pervades as if with the ambiguity of a future.

Portrait of Walter Serner

CHRISTIAN SCHAD

Living with his subject, Schad was instrumental in creating a movement that he himself ultimately wanted no part of. Walter Serner, depicted here, was the founder of a seminal Dada magazine that Schad, as his roommate, was credited as co-founder and contributed most of the graphic design for. Together in Zurich the two men had front row seats to the radical group that recontextualised the very meaning of art he began to paint inspired, as if through osmosis, by Dada, Cubism, Futurism and Impressionism. The fractured, geometric forms that overtake the portrait create a sense of a broken mirror, and the fallability of all portraiture. Yet, in the following years, Schad spent increasing time in Italy and the movements that had existed around him paled in comparison to the beauty he saw in Rafael, in the delicate, incisive brushstrokes of the Renaissance that he all but abandoned the visual style of the avant-garde, creating works of traditional and breath-taking beauty that dealt with the same conceptual ideas as his contemporaries but owed their debt to a time gone by.

Christain Schad

CHRISTIAN SCHAD, 1916. OIL ON CANVAS.

Living with his subject, Schad was instrumental in creating a movement that he himself ultimately wanted no part of. Walter Serner, depicted here, was the founder of a seminal Dada magazine that Schad, as his roommate, was credited as co-founder and contributed most of the graphic design for. Together in Zurich the two men had front row seats to the radical group that recontextualised the very meaning of art he began to paint inspired, as if through osmosis, by Dada, Cubism, Futurism and Impressionism. The fractured, geometric forms that overtake the portrait create a sense of a broken mirror, and the fallability of all portraiture. Yet, in the following years, Schad spent increasing time in Italy and the movements that had existed around him paled in comparison to the beauty he saw in Rafael, in the delicate, incisive brushstrokes of the Renaissance that he all but abandoned the visual style of the avant-garde, creating works of traditional and breath-taking beauty that dealt with the same conceptual ideas as his contemporaries but owed their debt to a time gone by.

Study for “Swing Landscape”

STUART DAVIS

In Jazz music, a basic chord structure is improvised on by musicians, creating new and unlikely combinations and songs from a base starting point. Stuart Davis’ paintings can be understood in the same way; he worked within a theme, painting series of similar images where he would alter the color, the geometric composition and scale but retain the base formal components. Employed by the Works Progress Administration, that gave artists jobs painting murals during the Great Depression, he was fiercely patriotic, depicting America in joyous reverie. His works are jazz ballads, loose and unstructured by rich in emotion in movement. This is a fragment of a preparatory work of his masterpiece, “Swing Landscape”. It depicts workers at a dock, abstracted and frenetic. There is an inherent optimism to Davis’ paintings of contemporary life, he renders labour and leisure in the same vivid style, uplifting the everyday occasion into musicality.

Stuart Davis

STUART DAVIS, 1938. OIL ON CANVAS.

In Jazz music, a basic chord structure is improvised on by musicians, creating new and unlikely combinations and songs from a base starting point. Stuart Davis’ paintings can be understood in the same way; he worked within a theme, painting series of similar images where he would alter the color, the geometric composition and scale but retain the base formal components. Employed by the Works Progress Administration, that gave artists jobs painting murals during the Great Depression, he was fiercely patriotic, depicting America in joyous reverie. His works are jazz ballads, loose and unstructured by rich in emotion in movement. This is a fragment of a preparatory work of his masterpiece, “Swing Landscape”. It depicts workers at a dock, abstracted and frenetic. There is an inherent optimism to Davis’ paintings of contemporary life, he renders labour and leisure in the same vivid style, uplifting the everyday occasion into musicality.

Flower Day

DIEGO RIVERA

What appears at first as a quaint depiction of Mexican street life hides radical and political ideas behind it’s metropolitan idealism. Rivera casts a long shadow across the history of 20th Century Art, synthesising Pan-American influences, Renaissance frescoes, cubist philosophies, Aztec culture and socialist realism into an aesthetically powerfully and socially engaged oeuvre. Flower sellers were a subject he would return to repeatedly across his career, visiting them in murals, frescoes and paintings, but this is his first ever depiction of the theme that would stay with him for decades. The piece praises labour, it can be read as a celebration of work with the flower seller as it’s hero. It is notably, too, that she sells goods with a purely aesthetic value, and remains dignified in doing so – Rivera saw himself and all artists in the quiet power of the flower selling, ensuring that the work of creation visual beauty was seen as dignified.

Diego Rivera

DIEGO RIVERA, 1925. OIL ON CANVAS.

What appears at first as a quaint depiction of Mexican street life hides radical and political ideas behind it’s metropolitan idealism. Rivera casts a long shadow across the history of 20th Century Art, synthesising Pan-American influences, Renaissance frescoes, cubist philosophies, Aztec culture and socialist realism into an aesthetically powerfully and socially engaged oeuvre. Flower sellers were a subject he would return to repeatedly across his career, visiting them in murals, frescoes and paintings, but this is his first ever depiction of the theme that would stay with him for decades. The piece praises labour, it can be read as a celebration of work with the flower seller as it’s hero. It is notably, too, that she sells goods with a purely aesthetic value, and remains dignified in doing so – Rivera saw himself and all artists in the quiet power of the flower selling, ensuring that the work of creation visual beauty was seen as dignified.

The Kiss

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

Two lovers are dissolved into a pure, single, abstract form in the first sculpture of modernism. Brancusi’s choice of a kiss to make this radical, revolutionary action was no mistake. In a fell swoop he was situating himself in pantheon of art history and making all the painted and sculpture depictions of romance that came before him seem old fashioned. Throughout the rest of his life he would come back again and again to this sculpture, creating new versions that were simpler, more formalistic than the ones before. Yet here is the first, a proto-cubist rendering that reduces the most natural of acts into art that approaches geometry. Inspired by African, Assyrian and Egyptian art, ‘The Kiss’ created a new language of Western Sculpture by subverting one of its most sustained motifs.

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI, 1908. PLASTER.

Two lovers are dissolved into a pure, single, abstract form in the first sculpture of modernism. Brancusi’s choice of a kiss to make this radical, revolutionary action was no mistake. In a fell swoop he was situating himself in pantheon of art history and making all the painted and sculpture depictions of romance that came before him seem old fashioned. Throughout the rest of his life he would come back again and again to this sculpture, creating new versions that were simpler, more formalistic than the ones before. Yet here is the first, a proto-cubist rendering that reduces the most natural of acts into art that approaches geometry. Inspired by African, Assyrian and Egyptian art, ‘The Kiss’ created a new language of Western Sculpture by subverting one of its most sustained motifs.

Sunflowers

JOAN MITCHELL

Balanced on fragile stalks, the sunflower is a pure concentration of mass and color that forces its way upwards to bloom in splendour, only to droop and wilt so visibly as to almost express the sadness of its mortality. This oddly human quality was exactly what Mitchell saw in the flowers, treating them ‘like people’ and returning to them over 40 years. The title of her works were decided after they were painted, drawing on the feelings and states she was in during their production. So, the Sunflower series are made in momnts of pride and fradility, their frenetic confident brushstrokes a mask for the delicateness of spirit. “If I see a sunflower drooping, I can droop with it”, she explained, “and I draw it, and feel it until its death”.

Joan Mitchell

JOAN MITCHELL, 1991. OIL ON CANVAS

Balanced on fragile stalks, the sunflower is a pure concentration of mass and colour that forces its way upwards to bloom in splendour, only to droop and wilt so visibly as to almost express the sadness of its mortality. This oddly human quality was exactly what Mitchell saw in the flowers, treating them ‘like people’ and returning to them over 40 years. The title of her works were decided after they were painted, drawing on the feelings and state she was in during their production. So, the Sunflower series are made in moments of pride and fragility, their frenetic, confident brushstrokes a mask for the delicateness of spirit. ‘'If I see a sunflower drooping, I can droop with it,' she explained, 'and I draw it, and feel it until its death.'

Christ Carrying The Cross

EL GRECO

El Greco wasn’t telling a story. This work is not narrative, unlike so much religious art — instead, it is a moment in time, a devotional image to meditate on and consider. We see Christ in a moment of personal reflection, his gaze upwards towards God and his hands gently wrapping around the instrument of his death. We find him in the quiet; alone, a storm brewing behind him, and we join him in this contemplation. It is raw, expressive, immersive, and aching. Deeply human as we see the pain bubbling into Christs eyes yet all the while, the scene is otherworldly. Every decision El Greco made was in service of this duality, from the deep, rich colors of Christ’s dress to the fluid, organic brushstrokes that define his hands and body, Greco is not hiding his act of creation in this work. El Greco was not telling a story because he was asking us to consider a moment, to exist in a feeling and find ourselves and our meaning within it.

El Greco

EL GRECO c.1580. OIL ON CANVAS.

El Greco wasn’t telling a story. This work is not narrative, unlike so much religious art — instead, it is a moment in time, a devotional image to meditate on and consider. We see Christ in a moment of personal reflection, his gaze upwards towards God and his hands gently wrapping around the instrument of his death. We find him in the quiet; alone, a storm brewing behind him, and we join him in this contemplation. It is raw, expressive, immersive, and aching. Deeply human as we see the pain bubbling into Christs eyes yet all the while, the scene is otherworldly. Every decision El Greco made was in service of this duality, from the deep, rich colors of Christ’s dress to the fluid, organic brushstrokes that define his hands and body, Greco is not hiding his act of creation in this work. El Greco was not telling a story because he was asking us to consider a moment, to exist in a feeling and find ourselves and our meaning within it.

The Flight of the Dragonfly in Front of the Sun

JOAN MIRÓ

In the 1960s, Joan Miró began stripping away anything superfluous until all he was left with was unadulterated expression. Gone were the playful flourishes of his earlier abstractions, the human-like quality of his shapes, the kinetic movement and subtle shading of his figures and planes. In their place, plumbed from the depths of his consciousness, was simplicity. The flight of the dragonfly needs nothing more than a line to speak of its movement and it is dwarfed by the enormity, and irregularity, of the sun. Miro began to paint not seeking representation or even emotion but a sort of unplaceable familiarity. If he reduced the world around him to core elements, and depicted the world as filtered through memory and experience, he could capture the purest essence of existence. The flight of the dragonfly is not about the dragonfly but about how both the smallest being and the largest concepts should take up the same space together.

Joan Miró

JOAN MIRÓ, 1968. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the 1960s, Joan Miró began stripping away anything superfluous until all he was left with was unadulterated expression. Gone were the playful flourishes of his earlier abstractions, the human-like quality of his shapes, the kinetic movement and subtle shading of his figures and planes. In their place, plumbed from the depths of his consciousness, was simplicity. The flight of the dragonfly needs nothing more than a line to speak of its movement and it is dwarfed by the enormity, and irregularity, of the sun. Miro began to paint not seeking representation or even emotion but a sort of unplaceable familiarity. If he reduced the world around him to core elements, and depicted the world as filtered through memory and experience, he could capture the purest essence of existence. The flight of the dragonfly is not about the dragonfly but about how both the smallest being and the largest concepts should take up the same space together.