Woman in Blue

CHAÏM SOUTINE

Pain, anguish, and poverty seem to materialise in tortured hands. The flesh and bones distort, fracture, expand, and contract in painful brushstrokes and Soutine, in his depiction of 10 digits, fills them with enough emotion to last a lifetime. Painted in the inter-war years, it depicts an unknown subject - normal for Soutine who rarely depicted anyone he had a personal connection with – whose anonymity does not dampen the psychological intensity of the work. Abstract in its colours and style yet traditional in subject, it never shies away from a seeming revulsion to flesh, creating a caricature of humanity that feels at once absurd and sharply observed. Soutine lived in abject poverty nearly all of his life, often forgoing food in favour of art supplies and channelling his literal hunger into inspiration and drive. The titular women in blue is a stand-in for Soutine himself, her pain is his, their shared lives built upon both universal hardship and the beautiful longing for more that accompanies it.

Chaïm Soutine

CHAÏM SOUTINE, c.1919. OIL ON CANVAS.

Pain, anguish, and poverty seem to materialise in tortured hands. The flesh and bones distort, fracture, expand, and contract in painful brushstrokes and Soutine, in his depiction of 10 digits, fills them with enough emotion to last a lifetime. Painted in the inter-war years, it depicts an unknown subject - normal for Soutine who rarely depicted anyone he had a personal connection with – whose anonymity does not dampen the psychological intensity of the work. Abstract in its colours and style yet traditional in subject, it never shies away from a seeming revulsion to flesh, creating a caricature of humanity that feels at once absurd and sharply observed. Soutine lived in abject poverty nearly all of his life, often forgoing food in favour of art supplies and channelling his literal hunger into inspiration and drive. The titular women in blue is a stand-in for Soutine himself, her pain is his, their shared lives built upon both universal hardship and the beautiful longing for more that accompanies it.

Prometheus Being Chained By Vulcan

DIRCK VAN BABUREN

Prometheus stole fire from the Gods and gave it to the mortals. In some versions of the story, it was he who crafted humans from clay and used the fire to imbue them with life, in others the fire was merely a tool to allow them to create civilisation. Yet in all tellings, the ending if the same; the great Titan Prometheus is bound to rock by the blacksmith God Vulcan, god of fire, volcanoes and deserts, and for eternity has his liver consumed by an eagle. It is one of many stories from the ancient world that artists of the Baroque drew their stories from yet is devoid of so much of the romance more commonly seen in the movement. Van Baburen’s depiction borrows heavily from the work of Renaissance artists before him, adapting Caravaggio’s depiction of St. Paul to become his Prometheus most notably. Yet for all the obvious influences, van Barburen brings new light to an ancient story and find the humanity, the religion and the beauty in myth.

Dirck van Baburen

DIRCK VAN BABUREN, 1623. OIL ON CANVAS.

Prometheus stole fire from the Gods and gave it to the mortals. In some versions of the story, it was he who crafted humans from clay and used the fire to imbue them with life, in others the fire was merely a tool to allow them to create civilisation. Yet in all tellings, the ending if the same; the great Titan Prometheus is bound to rock by the blacksmith God Vulcan, god of fire, volcanoes and deserts, and for eternity has his liver consumed by an eagle. It is one of many stories from the ancient world that artists of the Baroque drew their stories from yet is devoid of so much of the romance more commonly seen in the movement. Van Baburen’s depiction borrows heavily from the work of Renaissance artists before him, adapting Caravaggio’s depiction of St. Paul to become his Prometheus most notably. Yet for all the obvious influences, van Barburen brings new light to an ancient story and find the humanity, the religion and the beauty in myth.

Purification of the Temple

EL GRECO

An angry Christ drove the moneychangers out of the Temple, flipping their tables in disgust at the heresy they showed. Though one of the most common contemporary stories from the New Testament, it was not a popular theme of painting for most of the Renaissance, presenting a side of Christ that seemed counter to the beauty and divinity so much of the work strove for. Yet El Greco returned to this subject multiple times throughout his career, and at the turn of the 1600s, it began to take on radically new meaning. As Protestantism began to rise across Europe, the Catholic Church saw this story as an analogy for their attempt to purify themselves from the scourge of this new religion. Protestantism was, for them, the heresy to true Christianity, and Christ driving the moneychangers out was inspiration for them to keep the Catholic faith pure and alive.

El Greco

EL GRECO, c.1600. OIL ON CANVAS.

An angry Christ drove the moneychangers out of the Temple, flipping their tables in disgust at the heresy they showed. Though one of the most common contemporary stories from the New Testament, it was not a popular theme of painting for most of the Renaissance, presenting a side of Christ that seemed counter to the beauty and divinity so much of the work strove for. Yet El Greco returned to this subject multiple times throughout his career, and at the turn of the 1600s, it began to take on radically new meaning. As Protestantism began to rise across Europe, the Catholic Church saw this story as an analogy for their attempt to purify themselves from the scourge of this new religion. Protestantism was, for them, the heresy to true Christianity, and Christ driving the moneychangers out was inspiration for them to keep the Catholic faith pure and alive.

Dada Head

HANS RICHTER

Living in Zurich during the war, Richter became the chronicler of the Dadaists with his naïve and intoxicating portraits. Before Tristan Tzara introduced him to a young filmmaker and Richter found his calling in moving pictures, it was painted, mixed media works like these that occupied his attention. Trying to paint using the principles of avant-garde music, using the negative space to offer moments of calm before slowly rising to a crescendo, Richter applied the philosophy of an aphysical medium to the page. As he moved through the 1910s, these portraits got increasingly abstract, and the multiple portraits he painted across his career tell the story of a movement away from the external world and into an inner life. Richter’s experimental films, some of the very first to ever be made, owe a debt to his painterly work. In pushing the boundaries of one medium, he was able to open up unknown potential in another.

Hans Richter

HANS RICHTER, 1918. INK AND CHARCOAL ON PAPER.

Living in Zurich during the war, Richter became the chronicler of the Dadaists with his naïve and intoxicating portraits. Before Tristan Tzara introduced him to a young filmmaker and Richter found his calling in moving pictures, it was painted, mixed media works like these that occupied his attention. Trying to paint using the principles of avant-garde music, using the negative space to offer moments of calm before slowly rising to a crescendo, Richter applied the philosophy of an aphysical medium to the page. As he moved through the 1910s, these portraits got increasingly abstract, and the multiple portraits he painted across his career tell the story of a movement away from the external world and into an inner life. Richter’s experimental films, some of the very first to ever be made, owe a debt to his painterly work. In pushing the boundaries of one medium, he was able to open up unknown potential in another.

Portrait of Dr. Felix J. Weil

GEORGE GROSZ

Grosz rejected the expressionist spirit that was overtaking European art in the early decades of the 20th Century. He saw their style as self-involved, uncommitted to reality in its yearning for romantic ideals which could never be and resented the personality cults that the artists of the movements cultivated, willingly or not, around them. ‘The cult of individuality and personality, which promotes painters and poets only to promote itself, is really a business.”, he said, “The greater the 'genius' of the personage, the greater the profit.” Instead, Grosz was at the forefront of a style known as New Objectivism, which was about practical and honest engagement with the world, rid of pretentions or fancy instead the artists would try and represent the world as it appeared and find the art in the truthful imperfections around them. His portraiture came to define this style, austere and honest, he depicts people as they were, creating historical records that aspire to little more than the beauty of the everyday.

George Grosz

GEORGE GROSZ, 1926. OIL ON CANVAS.

Grosz rejected the expressionist spirit that was overtaking European art in the early decades of the 20th Century. He saw their style as self-involved, uncommitted to reality in its yearning for romantic ideals which could never be and resented the personality cults that the artists of the movements cultivated, willingly or not, around them. ‘The cult of individuality and personality, which promotes painters and poets only to promote itself, is really a business.”, he said, “The greater the 'genius' of the personage, the greater the profit.” Instead, Grosz was at the forefront of a style known as New Objectivism, which was about practical and honest engagement with the world, rid of pretentions or fancy instead the artists would try and represent the world as it appeared and find the art in the truthful imperfections around them. His portraiture came to define this style, austere and honest, he depicts people as they were, creating historical records that aspire to little more than the beauty of the everyday.

Premiere

STUART DAVIS

On the precipice of modernity, the long shadow of the Second World War starting to wane and the art forms that had sprung up in its wake becoming tired and clichéd, Stuart Davis built a bridge. The geometric abstractions, colour-field paintings, modernist simplifications and abstract expressionists that had dominated the aesthetic language for preceding decade meet with the burgeoning pop-art style, neither named nor acknowledged at scale at the time this work was made. Consumer products and bold slogans of capitalism and commerce combine with jazz-inspired formalism, to create a work that refuses to fit neatly into any genre. Davis was a visionary, and ahead of his time at every stage of his career. He was acutely aware of the political purpose of his art, and used his medium to push the discourse and the vision of a better future, and comment on the idiosyncrasies and flaws of the present he was living in.

Stuart Davis

STUART DAVIS, 1957. OIL ON CANVAS.

On the precipice of modernity, the long shadow of the Second World War starting to wane and the art forms that had sprung up in its wake becoming tired and clichéd, Stuart Davis built a bridge. The geometric abstractions, colour-field paintings, modernist simplifications and abstract expressionists that had dominated the aesthetic language for preceding decade meet with the burgeoning pop-art style, neither named nor acknowledged at scale at the time this work was made. Consumer products and bold slogans of capitalism and commerce combine with jazz-inspired formalism, to create a work that refuses to fit neatly into any genre. Davis was a visionary, and ahead of his time at every stage of his career. He was acutely aware of the political purpose of his art, and used his medium to push the discourse and the vision of a better future, and comment on the idiosyncrasies and flaws of the present he was living in.

Self-Portait

VINCENT VAN GOGH

“People say – and I’m quite willing to believe it – that it’s difficult to know oneself – but it’n not easy to paint oneself either”, so said Van Gogh in one of his many letters to his brother Theo. Yet for all the difficulty, or perhaps because of it, Van Gogh did paint himself, constantly and almost obsessively in his short-lived artistic life. Often from the same angle, with his face at three quarters to the view, Van Gogh documented his changing life, mind, and health with each new self-portrait and from the clues that are hidden within them we can learn enormous amounts about his life. This painting was perhaps his first since he moved to Paris, seeking out the new style of French painting he had heard of. He documents himself as a fashionable Parisian, bourgeois with an elegant suit and well fitted straw hat, in rhythmic, hypnotic brushstrokes. Yet Van Gogh never quite felt comfortable as the figure he tried to depict here, this portrait was a version of himself and you can see, in his eyes, that it does not match his true spirit.

Vincent van Gogh

VINCENT VAN GOGH, 1887. OIL ON PASTELBOARD.

“People say – and I’m quite willing to believe it – that it’s difficult to know oneself – but it’n not easy to paint oneself either”, so said Van Gogh in one of his many letters to his brother Theo. Yet for all the difficulty, or perhaps because of it, Van Gogh did paint himself, constantly and almost obsessively in his short-lived artistic life. Often from the same angle, with his face at three quarters to the view, Van Gogh documented his changing life, mind, and health with each new self-portrait and from the clues that are hidden within them we can learn enormous amounts about his life. This painting was perhaps his first since he moved to Paris, seeking out the new style of French painting he had heard of. He documents himself as a fashionable Parisian, bourgeois with an elegant suit and well fitted straw hat, in rhythmic, hypnotic brushstrokes. Yet Van Gogh never quite felt comfortable as the figure he tried to depict here, this portrait was a version of himself and you can see, in his eyes, that it does not match his true spirit.

Actual Size

ED RUSCHA

Words, humour, and the great American iconography are the three themes that underpin so much of Ruscha’s work. Actual Size is a perfect synthesis of these ideas in this period, operating on multiple levels as both an artwork and a visual joke. Painted the same year that Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans were shown, it was part of a new movement in art that co-opted the insignia and objects of American Life and elevated them into art forms. Yet Ruscha went one step further than Warhol – rather than simply depicting the product and its wordmark, he took inspiration from Chuck Yeager, an early astronaut and flying ace, who described took issue with the new, heavily automated spaceships that reduced their pilots to simple being ‘Spam in a Can’. Ruscha’s Spam takes flight, leaving a streak behind it as it soars across the white field. This is a monumental work that brings us in and out of context, recontextualising the word and the product while also serving as an ode to the great American processed meat.

Ed Ruscha

ED RUSHCA, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS.

Words, humour, and the great American iconography are the three themes that underpin so much of Ruscha’s work. Actual Size is a perfect synthesis of these ideas in this period, operating on multiple levels as both an artwork and a visual joke. Painted the same year that Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans were shown, it was part of a new movement in art that co-opted the insignia and objects of American Life and elevated them into art forms. Yet Ruscha went one step further than Warhol – rather than simply depicting the product and its wordmark, he took inspiration from Chuck Yeager, an early astronaut and flying ace, who described took issue with the new, heavily automated spaceships that reduced their pilots to simple being ‘Spam in a Can’. Ruscha’s Spam takes flight, leaving a streak behind it as it soars across the white field. This is a monumental work that brings us in and out of context, recontextualising the word and the product while also serving as an ode to the great American processed meat.

The Crucifixion

UNKNOWN AUSTRIAN MASTER

In the fledgling beginnings of the Northern Renaissance, removed the cultural epicentre of Italy whose artistic style was progressing ahead of its northern neighbours, artists were rediscovering a representational style that had been lost for centuries. Perspectival drawing was mastered by the ancient world who, across generations of trial and error, discovered the secrets to representing a three-dimensional world onto a flat plane. But in the preceding centuries, the skills and knowledge of this style were lost – until, that is, the arrival of the renaissance at the end of 14th century. In the early decades of this revolution, we can witness the evolution of this style in real time, watch masterful artists create life from tempera, wood and brushes, and, in their completed works, see the successes and the failures go hand in hand. The results are poignant and surreal, as exemplified in this work by an unknown Austrian master. Figures’ scale changes with no relation to their positioning on the canvas, but this allows us to see their expressions more clearly. Detailed faces seem to sit in biologically impossible positions which only emphasises the anguish. For each imperfection, something is gained, and the immaculate detail of this work, both in narrative and emotion, is possible only for the slight naivety of its style.

Unknown Austrian Master

AUSTRIAN MASTER, c.1410. TEMPERA AND GOLD ON WOOD PANEL.

In the fledgling beginnings of the Northern Renaissance, removed the cultural epicentre of Italy whose artistic style was progressing ahead of its northern neighbours, artists were rediscovering a representational style that had been lost for centuries. Perspectival drawing was mastered by the ancient world who, across generations of trial and error, discovered the secrets to representing a three-dimensional world onto a flat plane. But in the preceding centuries, the skills and knowledge of this style were lost – until, that is, the arrival of the renaissance at the end of 14th century. In the early decades of this revolution, we can witness the evolution of this style in real time, watch masterful artists create life from tempera, wood and brushes, and, in their completed works, see the successes and the failures go hand in hand. The results are poignant and surreal, as exemplified in this work by an unknown Austrian master. Figures’ scale changes with no relation to their positioning on the canvas, but this allows us to see their expressions more clearly. Detailed faces seem to sit in biologically impossible positions which only emphasises the anguish. For each imperfection, something is gained, and the immaculate detail of this work, both in narrative and emotion, is possible only for the slight naivety of its style.

Tennis Tournament

GEORGE BELLOWS

When he passed away at the age of 42, George Bellows was regarded as one of the greatest American artists of his day. Today, his fame has waned and he is no longer the household name he once was. Yet Bellows is well worth remembering for his vivid, enigmatic and striking portraits of New York, that straddled class and politics. Bellows was part of a group of anarchist, liberal artists and activists known as ‘The Lyrical Left’, advocating for individual rights and freedom. Yet Bellows was often at odds with the group – he saw artistic freedom as tantamount, and far more important than ideological politics. Bellows depicted tenement housing, boxing matches and the lower classes of the city, but he also mingled with the high society. Here, he depicts a tennis tournament in Rhode Island as both a social event and a sporting one. His interest is in the setting, the atmosphere, the palpable, searing heat, more than it is about the tennis. He captures a slice of life, a vignette of existence in broad, vivid strokes.

George Bellows

GEORGE BELLOWS, 1920. OIL ON CANVAS.

When he passed away at the age of 42, George Bellows was regarded as one of the greatest American artists of his day. Today, his fame has waned and he is no longer the household name he once was. Yet Bellows is well worth remembering for his vivid, enigmatic and striking portraits of New York, that straddled class and politics. Bellows was part of a group of anarchist, liberal artists and activists known as ‘The Lyrical Left’, advocating for individual rights and freedom. Yet Bellows was often at odds with the group – he saw artistic freedom as tantamount, and far more important than ideological politics. Bellows depicted tenement housing, boxing matches and the lower classes of the city, but he also mingled with the high society. Here, he depicts a tennis tournament in Rhode Island as both a social event and a sporting one. His interest is in the setting, the atmosphere, the palpable, searing heat, more than it is about the tennis. He captures a slice of life, a vignette of existence in broad, vivid strokes.

The Tower of Babel

PIETER BRUEGEL

‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.’ A unified, monolingual human race, working together as they traverse eastward come to the land of Shinar and begin to build a tower, high up into the sky. Yahweh, seeing them rise higher to the heavens and feeling threatened by the power of a species that can all communicate, confounds their speech, creating hundreds of different of languages so they can no longer understand each other, and the tower begins to break, scattering them all over the world. This is the story that Bruegel is telling, one of hubris and futility, of humans who aspire to divinity and have their pride punished. He paints the tower before it’s destruction, being built in a spiral upwards, but there are cracks showing and we see bricks beginning to fall. We are, he is trying to tell us, so arrogant to think we can reach God when our earthly craftsmanship is not even able to build a strong tower.

Pieter Bruegel

PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER, c.1563. OIL ON WOOD.

‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.’ A unified, monolingual human race, working together as they traverse eastward come to the land of Shinar and begin to build a tower, high up into the sky. Yahweh, seeing them rise higher to the heavens and feeling threatened by the power of a species that can all communicate, confounds their speech, creating hundreds of different of languages so they can no longer understand each other, and the tower begins to break, scattering them all over the world. This is the story that Bruegel is telling, one of hubris and futility, of humans who aspire to divinity and have their pride punished. He paints the tower before it’s destruction, being built in a spiral upwards, but there are cracks showing and we see bricks beginning to fall. We are, he is trying to tell us, so arrogant to think we can reach God when our earthly craftsmanship is not even able to build a strong tower.

Untitled (Know nothing, Believe anything, Forget everything)

BARBARA KRUGER

We are living in a world Barbara Kruger predicted, criticised, and one she accidentally helped create. It is because of this that it’s easy to misread her critique and her skewering as endorsement. Her text-on-image works that started in the late 1970s were a radical attack on commercialism, a call to arms for women to open their eyes to a capitalist society trying to commodify themselves. For nearly 50 years, Kruger has been creating works that juxtapose archival imagery with her direct statements, commands to the viewer that remove the subtext from the advertising copy we are inundated with. She used the tactics of advertising and media industries, tactics designed steal time and arrest the viewer, to subvert the message of the medium. It is perhaps ironic then, that her italic, capitalised Futura font words have since adorned hundreds of thousands of t-shirts, skateboards and well-hyped products from the streetwear brand Supreme who co-opted Kruger’s signature style. Kruger has been commodified by a world she fought against, but her work still cuts through, more urgent than ever before.

Barbara Kruger

BARABRA KRUGER, 1987. SCREENPRINT ON VINYL.

We are living in a world Barbara Kruger predicted, criticised, and one she accidentally helped create. It is because of this that it’s easy to misread her critique and her skewering as endorsement. Her text-on-image works that started in the late 1970s were a radical attack on commercialism, a call to arms for women to open their eyes to a capitalist society trying to commodify themselves. For nearly 50 years, Kruger has been creating works that juxtapose archival imagery with her direct statements, commands to the viewer that remove the subtext from the advertising copy we are inundated with. She used the tactics of advertising and media industries, tactics designed steal time and arrest the viewer, to subvert the message of the medium. It is perhaps ironic then, that her italic, capitalised Futura font words have since adorned hundreds of thousands of t-shirts, skateboards and well-hyped products from the streetwear brand Supreme who co-opted Kruger’s signature style. Kruger has been commodified by a world she fought against, but her work still cuts through, more urgent than ever before.

Still Life: The Table

GEORGES BRAQUE

To upend art history, you have to be committed to its traditions. For Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, who together created the visual vocabulary of modernity, this tradition began and would be dismantled with the ‘Still Life’. Using the motifs, objects and arrangements that have pervaded painted works for centuries, they disorientate the viewer while giving just enough context and knowledge to ground them. To look at Braque’s work today is to see it fitting neatly within the very art history he sought to topple, but this still life was a radical work. We are given the base of a table, its legs strangely foreshortened but it places us within a known entity. So too, the objects are familiar iconography – fruit, a guitar, a stoneware jug, music sheets and others. Yet each object has it’s own perspective, it does not conform within a singular vision but instead shows a world of multiplicity. Braque’s table could be viewed from infinite angles and still the objects upon it would never unify.

Georges Braque

GEORGES BRAQUE, 1928. OIL ON CANVAS.

To upend art history, you have to be committed to its traditions. For Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, who together created the visual vocabulary of modernity, this tradition began and would be dismantled with the ‘Still Life’. Using the motifs, objects and arrangements that have pervaded painted works for centuries, they disorientate the viewer while giving just enough context and knowledge to ground them. To look at Braque’s work today is to see it fitting neatly within the very art history he sought to topple, but this still life was a radical work. We are given the base of a table, its legs strangely foreshortened but it places us within a known entity. So too, the objects are familiar iconography – fruit, a guitar, a stoneware jug, music sheets and others. Yet each object has it’s own perspective, it does not conform within a singular vision but instead shows a world of multiplicity. Braque’s table could be viewed from infinite angles and still the objects upon it would never unify.

Mojave

ARSHILE GORKY

An Armenian refugee, escaping the genocide, who took on the name of Georgian nobility and became one of America’s most influential and important painters, Gorky remains to this day enigmatic and illusive. Though his work does not immediately appear of the genre, Gorky was the spiritual founder of Abstract Expressionism. Andre Breton tried to claim him as a surrealist and the Paris School and New York School of Artists both consider Gorky a profound influence. His work is lyrically abstract, using biomorphic forms that simultaneously express pure emotion, transferred from mind to hand with no interference from the conscious, while being unplaceably figurative. He was a bridge between languages, inspiring the visual linguists who came after him and changing the way his contemporaries thought. More than just bridging movements, Gorky was a connection between European and American art worlds, fostering trans-Atlantic relationships that shrunk the world around him into a unified, collaborative place.

Arshile Gorky

ARSHILE GORKY, 1941. OIL ON CANVAS.

An Armenian refugee, escaping the genocide, who took on the name of Georgian nobility and became one of America’s most influential and important painters, Gorky remains to this day enigmatic and illusive. Though his work does not immediately appear of the genre, Gorky was the spiritual founder of Abstract Expressionism. Andre Breton tried to claim him as a surrealist and the Paris School and New York School of Artists both consider Gorky a profound influence. His work is lyrically abstract, using biomorphic forms that simultaneously express pure emotion, transferred from mind to hand with no interference from the conscious, while being unplaceably figurative. He was a bridge between languages, inspiring the visual linguists who came after him and changing the way his contemporaries thought. More than just bridging movements, Gorky was a connection between European and American art worlds, fostering trans-Atlantic relationships that shrunk the world around him into a unified, collaborative place.

Signac and His Friends in the Sailing Boat

PIERRE BONNARD

Pierre Bonnard was a member of Les Nabis, an avant-garde, post-impressionist group of radical artists joined by a belief that art was not intended to represent nature but was instead a synthesis of symbols and metaphors of the artists ideas. His paintings were cosmopolitan, depicting urban life and intimate domestic scenes, and the forays into landscapes were static and devoid of human presence. Paul Signac, on the other hand, was a Pointillist who, together with Georges Seurat, created the new style of painting and used it to depict scenes of rural and Mediterranean life, alive with joyous, relaxed civilisation. So it should come as no surprise then, that this somewhat anomalous work in Bonnard’s career features at its centre a depiction of his friend from across the aisle, Signac. It is not just a literal depiction of him, surrounded by his friends helming a sailing boat, but Bonnard takes its further and paints like Signac, not in style but in content and feel. The work is alive, jubilant and reverent of nature – the philosophy of a companion translated through his personal lens.

Pierre Bonnard

PIERRE BONNARD, c.1924. OIL ON CANVAS.

Pierre Bonnard was a member of Les Nabis, an avant-garde, post-impressionist group of radical artists joined by a belief that art was not intended to represent nature but was instead a synthesis of symbols and metaphors of the artists ideas. His paintings were cosmopolitan, depicting urban life and intimate domestic scenes, and the forays into landscapes were static and devoid of human presence. Paul Signac, on the other hand, was a Pointillist who, together with Georges Seurat, created the new style of painting and used it to depict scenes of rural and Mediterranean life, alive with joyous, relaxed civilisation. So it should come as no surprise then, that this somewhat anomalous work in Bonnard’s career features at its centre a depiction of his friend from across the aisle, Signac. It is not just a literal depiction of him, surrounded by his friends helming a sailing boat, but Bonnard takes its further and paints like Signac, not in style but in content and feel. The work is alive, jubilant and reverent of nature – the philosophy of a companion translated through his personal lens.

Anthropometrie

YVES KLEIN

Klein replaced the paintbrush with the body. Working in collaboration with models covered in his signature blue paint, he instructed and directed them to push themselves against canvas and paper to leave remnants, ghostly leftovers, of their own form. This was a radical and controversial movement, not only for the perceived lewdness of the process, but because it took art our of the frame and placed it into everyday surroundings. It guided a passage from the material to the immaterial realm, beckoning in a transcendent idea of art that Klein believed in, one where the gulf between the human and the heavenly disappeared. On a visit to Hiroshima, Klein saw the impression of a man seared into stone, the mark of pain and destruction integrated man into the eternal nature that surrounded him. With more joy, freedom and intention, Klein was attempting the same with his Anthropometrie series. Bodies, flesh, and humans are mortal and transient, but we can coalesce with nature to rise above our mortality and reach the divine.

Yves Klein

YVES KLEIN, 1962. OIL ON PAPER.

Yves Klein replaced the paintbrush with the body. Working in collaboration with models covered in his signature blue paint, he instructed and directed them to push themselves against canvas and paper to leave remnants, ghostly leftovers, of their own form. This was a radical and controversial movement, not only for the perceived lewdness of the process, but because it took art out of the frame and placed it into everyday surroundings. It guided a passage from the material to the immaterial realm, beckoning in a transcendent idea of art that Klein believed in, one where the gulf between the human and the heavenly disappeared. On a visit to Hiroshima, Klein saw the impression of a man seared into stone, the mark of pain and destruction integrated man into the eternal nature that surrounded him. With more joy, freedom and intention, Klein was attempting the same with his Anthropometrie series. Bodies, flesh, and humans are mortal and transient, but we can coalesce with nature to rise above our mortality and reach the divine.

Tea

HENRI MATISSE

In the years after the first World War, Matisse’s wild Fauvism waned, and he became less concerned with translating his pure expressions through brushstrokes and developed into a more sophisticated style. ‘Tea’ is the largest and amongst the most accomplished of this period, with touches of Impressionism in the dappled sunlight and broad strokes, it communicates the lushness and comfort of the scene with clarity and beauty. Yet look a little deeper and we see further clues of Matisse’s radical origins. The face of Marguerite is distorted and in the style of the African masks that both Matisse and Picasso found so much inspiration in. It is an extension of his seminal sculptures that increasingly abstracted a female face, yet here in exists in domestic harmony, less radical and more a part of everyday life. Matisse’s revolution was accepted by the world, and this painting is testament to it’s integration in daily life.

Henri Matisse

HENRI MATISSE, 191. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the years after the first World War, Matisse’s wild Fauvism waned, and he became less concerned with translating his pure expressions through brushstrokes and developed into a more sophisticated style. ‘Tea’ is the largest and amongst the most accomplished of this period, with touches of Impressionism in the dappled sunlight and broad strokes, it communicates the lushness and comfort of the scene with clarity and beauty. Yet look a little deeper and we see further clues of Matisse’s radical origins. The face of Marguerite is distorted and in the style of the African masks that both Matisse and Picasso found so much inspiration in. It is an extension of his seminal sculptures that increasingly abstracted a female face, yet here in exists in domestic harmony, less radical and more a part of everyday life. Matisse’s revolution was accepted by the world, and this painting is testament to it’s integration in daily life.

Self Portrait

REMBRANDT

Rembrandt’s house and possessions were repossessed. After years of success and acclaim, he had fallen on hard times and the year before this portrait was painted he had to satisfy his overdue creditors. In the midst of this personal turmoil, he did what he knew best and composed a self-portrait. Throughout his life, Rembrandt documented himself obsessively. We have so many self-portraits of the artist that they serve almost as a biography of his existence, tracking his meteoric rise and the joy of his artistry and success before moving into his reckoning with mortality and here, the reversion of his past glories. Rembrandt stares directly at us, his face sombre and his eyes heavy. The work is less technically perfect than much of his oeuvre, the paint thickly applied and lacking some of the fine detail of other portraits. Yet this leads to a more expressive work – the stresses and tribulations of his recent ordeals captured in tactility. He relinquishes technicality to show pain and sadness as raw, direct, and honest.

Rembrandt Van Rijn

REMBRANDT VAN RIJN, 1659. OIL ON CANVAS.

Rembrandt’s house and possessions were repossessed. After years of success and acclaim, he had fallen on hard times and the year before this portrait was painted he had to satisfy his overdue creditors. In the midst of this personal turmoil, he did what he knew best and composed a self-portrait. Throughout his life, Rembrandt documented himself obsessively. We have so many self-portraits of the artist that they serve almost as a biography of his existence, tracking his meteoric rise and the joy of his artistry and success before moving into his reckoning with mortality and here, the reversion of his past glories. Rembrandt stares directly at us, his face sombre and his eyes heavy. The work is less technically perfect than much of his oeuvre, the paint thickly applied and lacking some of the fine detail of other portraits. Yet this leads to a more expressive work – the stresses and tribulations of his recent ordeals captured in tactility. He relinquishes technicality to show pain and sadness as raw, direct, and honest.

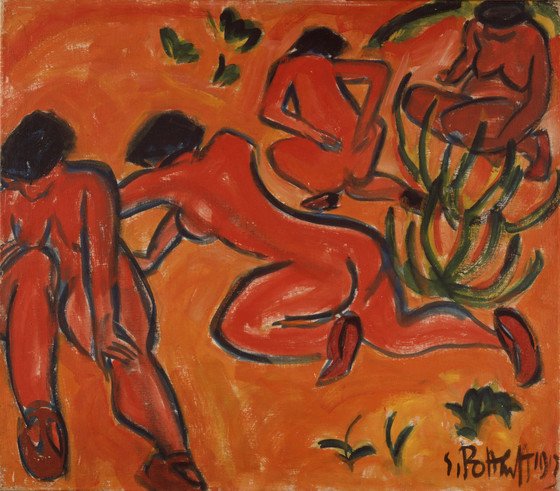

Bathers

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF

In an artists colony by the Baltic Sea, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and his colleagues within the German Expressionist group Die Brücke practiced a back to nature, free love, bohemian lifestyle. Their summers were as much an extension of their avant-grade art as their paintings were, living true to the same principles they applied to canvas. Nude bathers, taking the form of anonymous and objectified female forms, blend into a landscape with few signifiers save for sparse grass and loose dune like shapes. The image intentionally reveals little, it aspires instead to a universal sensation of summertime - the deep ochre acting as an oppressive sun that coats all it touches and the grit of the brushstrokes like the coarse grains of sand against the revellers bodies. Schmidt-Rottluff’s evocative images laid the groundwork for the Expressionists that followed him but few captured a lifestyle in harmony with their art quite so potently.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF, 1913. OIL ON CANVAS.

In an artists colony by the Baltic Sea, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and his colleagues within the German Expressionist group Die Brücke practiced a back to nature, free love, bohemian lifestyle. Their summers were as much an extension of their avant-grade art as their paintings were, living true to the same principles they applied to canvas. Nude bathers, taking the form of anonymous and objectified female forms, blend into a landscape with few signifiers save for sparse grass and loose dune like shapes. The image intentionally reveals little, it aspires instead to a universal sensation of summertime - the deep ochre acting as an oppressive sun that coats all it touches and the grit of the brushstrokes like the coarse grains of sand against the revellers bodies. Schmidt-Rottluff’s evocative images laid the groundwork for the Expressionists that followed him but few captured a lifestyle in harmony with their art quite so potently.

The Opera 'Messalina' at Bordeaux

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

Toulouse-Lautrec captured the decadence of his age. The publicity, the cabaret, the drama, the cafes, the restaurants and the spectacle of the turn of the century exudes from his oeuvre, capturing the subtleties and lack thereof that he lived within. The Opera was a recurring theme for him, sexually charged, high society drama replete with costumes and theatre – the subject and the painter were natural bedfellows. Born into aristocracy, a childhood accident rendered him very short as an adult due to his undersized legs and in Paris he found more comfort and kindness in the brothels and bars than the upper-class world of his birth. Yet he participated in both, an outsider who was allowed in and could keenly observe the idiosyncrasies and beauty of these mirroring existences.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC, 1900. OIL ON CANVAS.

Toulouse-Lautrec captured the decadence of his age. The publicity, the cabaret, the drama, the cafes, the restaurants and the spectacle of the turn of the century exudes from his oeuvre, capturing the subtleties and lack thereof that he lived within. The Opera was a recurring theme for him, sexually charged, high society drama replete with costumes and theatre – the subject and the painter were natural bedfellows. Born into aristocracy, a childhood accident rendered him very short as an adult due to his undersized legs and in Paris he found more comfort and kindness in the brothels and bars than the upper-class world of his birth. Yet he participated in both, an outsider who was allowed in and could keenly observe the idiosyncrasies and beauty of these mirroring existences.