Untitled (You Are A Very Special Person)

BARBARA KRUGER

Working as a magazine designer, Barbara Kruger came to innately understand the linguistic, typographic and visual conventions of consumerism. Single line slogans that sold disposable products week after week, images of airbrushed beauty that promoted shame, and direct instructions to the reader that their life could be better if only they did this, bought that, or changed something in themselves. A sort of meta-commentary on consumerism had been embedded in the art world since the advent of Pop, but Kruger took it beyond simple appropriation or decontextualisation. Her work combines found imagery with cut up phrases, often adulterated from their original form, to create images of a disquieting juxtaposition. The pieces feel immediately, viscerally familiar that to observe them is to question our own comfort with a visual language that wants something from us. Kruger makes us stop and question the inundation of messaging in our daily lives, and from a place of deep understanding forces a reflection on the power of words and images.

Barbara Kruger

BARBARA KRUGER, 1995. PHOTOGRAPHIC SILKSCREEN ON VINYL.

Working as a magazine designer, Barbara Kruger came to innately understand the linguistic, typographic and visual conventions of consumerism. Single line slogans that sold disposable products week after week, images of airbrushed beauty that promoted shame, and direct instructions to the reader that their life could be better if only they did this, bought that, or changed something in themselves. A sort of meta-commentary on consumerism had been embedded in the art world since the advent of Pop, but Kruger took it beyond simple appropriation or decontextualisation. Her work combines found imagery with cut up phrases, often adulterated from their original form, to create images of a disquieting juxtaposition. The pieces feel immediately, viscerally familiar that to observe them is to question our own comfort with a visual language that wants something from us. Kruger makes us stop and question the inundation of messaging in our daily lives, and from a place of deep understanding forces a reflection on the power of words and images.

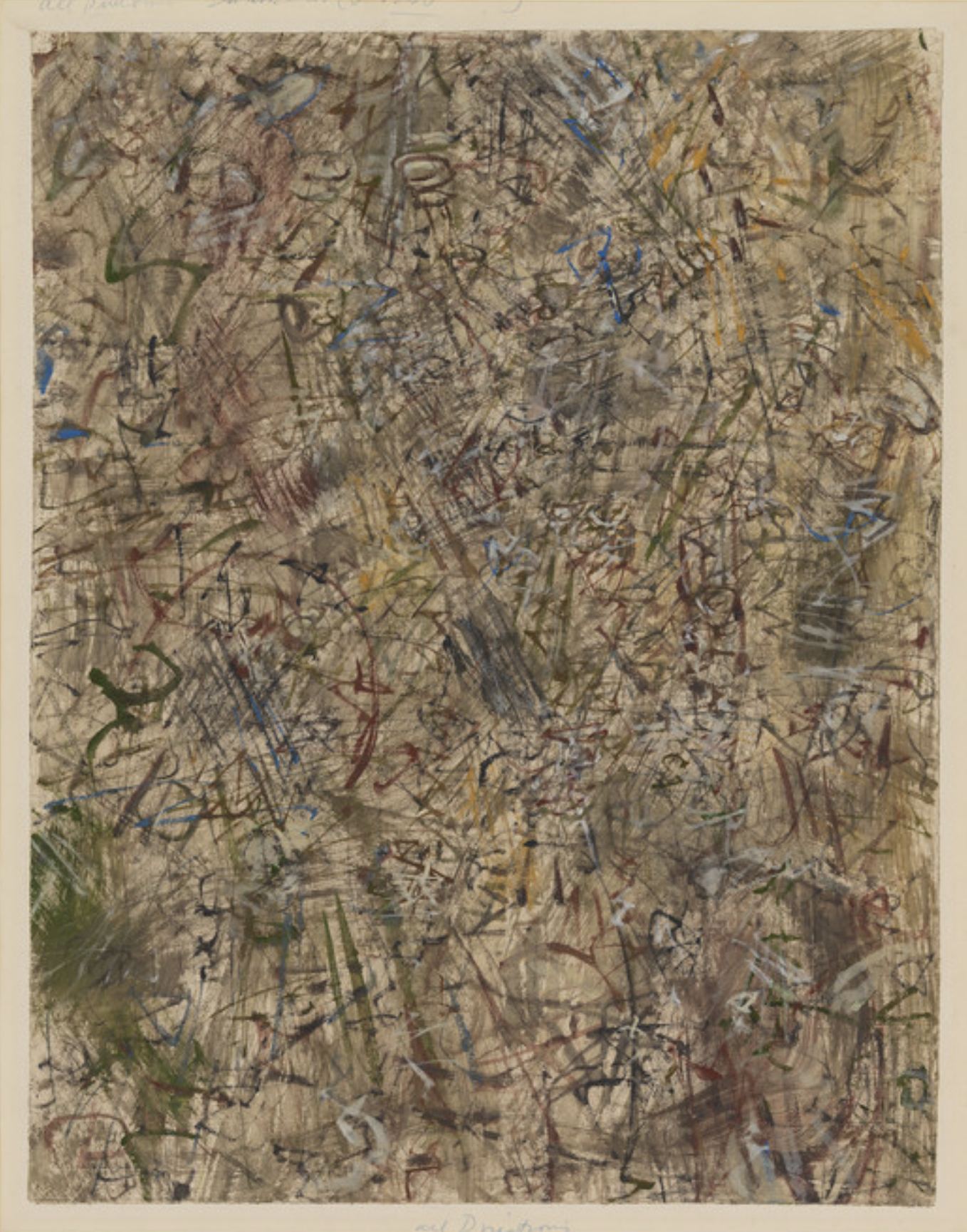

To Theo Van Gogh

KNUD MERRILD

In turn of the century Denmark, Merrild began his career as an apprentice house painter. The monotony of the work was meditative, and the techniques of paint mixing and application formed the basis of his most famous series of works. Yet, for all the influence his ‘Flux’ paintings had on 20th century abstract expressionism, Merrild worked as a house painter on occasion throughout his life, it serving as a financial bedrock in eras of low income. The ‘Flux’ paintings, such as the one here, were made by diluting oil paints into viscous, flowable forms, and dripping them onto the canvas in rhythmic motion to create post-surreal works that serve as a collaboration between Merrild and chance itself. Moving to America in the early 1920s, he became part of a group of writers that included D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Aldous Huxley, who all saw in the experimental Dane a kindred spirit who expressed his ideas of post-modernity through abstract forms rather than words.

Knud Merrild

KNUD MERRILD, 1951. OIL ON MASONITE.

In turn of the century Denmark, Merrild began his career as an apprentice house painter. The monotony of the work was meditative, and the techniques of paint mixing and application formed the basis of his most famous series of works. Yet, for all the influence his ‘Flux’ paintings had on 20th century abstract expressionism, Merrild worked as a house painter on occasion throughout his life, it serving as a financial bedrock in eras of low income. The ‘Flux’ paintings, such as the one here, were made by diluting oil paints into viscous, flowable forms, and dripping them onto the canvas in rhythmic motion to create post-surreal works that serve as a collaboration between Merrild and chance itself. Moving to America in the early 1920s, he became part of a group of writers that included D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Aldous Huxley, who all saw in the experimental Dane a kindred spirit who expressed his ideas of post-modernity through abstract forms rather than words.

Praying Hands

ALBRECHT DÜRER

Two hands gently pressed together in prayer, sketched as either preparation or posterity, have travelled the world over half a millennia. They have ended up on the tombstone of Andy Warhol, tattooed on thousands of bodies, recreated in endless variation and reproduced on every medium imaginable. Albrecht Dürer’s humble drawing has become, since it was created in the early 1500s, one of the most significant and iconic images of faith in the western world. It is because of this that various myths and stories as to its origin have sprung up over the years, each trying to find some contextual poetry in its creation that justifies its fame and acclaim. Yet the truth is more simple; the hands were painted as either a study for, or a record of, a detail in Dürer’s Heller Altarpiece. Immaculately rendered on precious blue paper there is no doubt Dürer was proud of the work, but their beauty does not come from a grand backstory or a tragic tale, simply from the devotion of an artist trying to capture the flesh and bones of faith in ink and paper.

Albrecht Dürer

ALBRECHT DÜRER, c.1508. PEN-AND-INK ON PAPER.

Two hands gently pressed together in prayer, sketched as either preparation or posterity, have travelled the world over half a millennia. They have ended up on the tombstone of Andy Warhol, tattooed on thousands of bodies, recreated in endless variation and reproduced on every medium imaginable. Albrecht Dürer’s humble drawing has become, since it was created in the early 1500s, one of the most significant and iconic images of faith in the western world. It is because of this that various myths and stories as to its origin have sprung up over the years, each trying to find some contextual poetry in its creation that justifies its fame and acclaim. Yet the truth is more simple; the hands were painted as either a study for, or a record of, a detail in Dürer’s Heller Altarpiece. Immaculately rendered on precious blue paper there is no doubt Dürer was proud of the work, but their beauty does not come from a grand backstory or a tragic tale, simply from the devotion of an artist trying to capture the flesh and bones of faith in ink and paper.

Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Guitar

AMÉDÉÉ OZENFANT

Art consists in the conception before anything else, and technique is merely a tool at the service of conception. These are two of the tenets of Purism, a movement founded in rebellion to the perceived ornamentation of Cubism by Ozenfant and, perhaps more significantly, Le Corbusier. In the war-torn France of 1918, ravaged by the First World War, Purism emerged as a way to bring back order. Cubism had become the de-facto school of Art and had strayed from it’s earliest intentions to become romantic and decorative, with an emphasis on detail that detracted from it’s radical, abstract origins. With Purism, Ozenfant and Corbusier focused on the essence of objects, free from details or decoration the forms are allowed to stand alone and find beauty in the simplicity of the world around us. It was a way to return to nature, without copying it, and while their unison ended, both Ozenfant and Corbusier held these ideas with them for the rest of their lives, and Le Corbusier used them to create the modern language of design and architecture.

Amédéé Ozenfant

AMÉDÉÉ OZENFANT, 1919. OIL ON CANVAS.

Art consists in the conception before anything else, and technique is merely a tool at the service of conception. These are two of the tenets of Purism, a movement founded in rebellion to the perceived ornamentation of Cubism by Ozenfant and, perhaps more significantly, Le Corbusier. In the war-torn France of 1918, ravaged by the First World War, Purism emerged as a way to bring back order. Cubism had become the de-facto school of Art and had strayed from it’s earliest intentions to become romantic and decorative, with an emphasis on detail that detracted from it’s radical, abstract origins. With Purism, Ozenfant and Corbusier focused on the essence of objects, free from details or decoration the forms are allowed to stand alone and find beauty in the simplicity of the world around us. It was a way to return to nature, without copying it, and while their unison ended, both Ozenfant and Corbusier held these ideas with them for the rest of their lives, and Le Corbusier used them to create the modern language of design and architecture.

Cows in Pasture

YASUO KUNIYOSHI

Born in a Year of the Cow, according the the Japanese calendar, it seemed obvious to Kuniyoshi that he would feel a kinship to these creatures. Invited to an art colony in Maine for the summer of 1920, surrounded by agricultural land and pastoral fields of grazing bovine, his paintings ‘usually began with cows’. Yet despite the ample opportunity, Kuniyoshi worked in the Japanese tradition of painting from memory, not from life. His subjects were a combination of visual recollection and idealistic imagination, resulting in subjects that were the ideals of their being, the platonic perfection of cows. This was combined with an influence of Cubism from the West that resulted in angular, geometric lines and reductions, producing images that bridged a cultural gap. Over the 1920s, he painted more than 60 works with cows as the central subjects. There is something in these works that speaks to the uniquely universal experience of agricultural, while still feeling reminiscent of deeply American way of life.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi

YASUO KUNIYOSHI, 1923. OIL ON CANVAS.

Born in a Year of the Cow, according the the Japanese calendar, it seemed obvious to Kuniyoshi that he would feel a kinship to these creatures. Invited to an art colony in Maine for the summer of 1920, surrounded by agricultural land and pastoral fields of grazing bovine, his paintings ‘usually began with cows’. Yet despite the ample opportunity, Kuniyoshi worked in the Japanese tradition of painting from memory, not from life. His subjects were a combination of visual recollection and idealistic imagination, resulting in subjects that were the ideals of their being, the platonic perfection of cows. This was combined with an influence of Cubism from the West that resulted in angular, geometric lines and reductions, producing images that bridged a cultural gap. Over the 1920s, he painted more than 60 works with cows as the central subjects. There is something in these works that speaks to the uniquely universal experience of agricultural, while still feeling reminiscent of deeply American way of life.

Sunlight

MAX PECHSTEIN

The ‘Die Brücke’ artists prided themselves on their crudeness. Like their French counterparts the Fauves, they rejected both total abstraction and realist depiction, disliking Impressionism’s focus on aesthetic beauty and the neutered, domestic subjects of Pointillism. They were the proton-expressionists, informed by primitive art and the raw expression of emotion, in subject matter explicit and erotic charged. Their very name ‘Die Brücke’, translates to ‘The Bridge’, an acknowledgement the group made that they were to be a bridge to the art of the future, a self fulfilling prophecy that ensured both their importance and their brief life. It was in the early days of this creatively enthused rebellion that a young Max Pechstein joined the group, and became the only artist with formal training to do so. This led, unsurprisingly, to a fractious relationship and resentment between the members, especially as Pechstein gained more commercial success than the others. He was expelled in 1912, and became a darling of the art world until he was vilified as a degenerate by the Nazi’s and his art removed from all institutions. His career revived after the war and Pechstein continued to paint and create to acclaim and through it all, his style always spoke to the Die Brückes. A member for only 6 years in a more than 50 year career but there was not a brushstroke painted that wasn’t informed by the wild philosophies of his youthful rebellion.

Max Pechstein

MAX PECHSTEIN, 1921. OIL ON CANVAS.

The ‘Die Brücke’ artists prided themselves on their crudeness. Like their French counterparts the Fauves, they rejected both total abstraction and realist depiction, disliking Impressionism’s focus on aesthetic beauty and the neutered, domestic subjects of Pointillism. They were the proton-expressionists, informed by primitive art and the raw expression of emotion, in subject matter explicit and erotic charged. Their very name ‘Die Brücke’ translates to ‘The Bridge’, a self fulfilling prophecy that ensured both their importance and brief life. It was in the early days of this creatively enthused rebellion that a young Max Pechstein joined the group, and became the only artist with formal training to do so. This led, unsurprisingly, to a fractious relationship and resentment between the members, especially as Pechstein gained more commercial success. He was expelled in 1912, and became a darling of the art world until he was vilified as a degenerate by the Nazi’s and his art removed from all institutions. His career revived after the war and Pechstein continued working to acclaim but through it all, his style always spoke to Die Brückes. A member for only 6 years in his more than 50 year career, but there was not a brushstroke painted that wasn’t informed by the wild philosophies of his youthful rebellion.

The Club

JEAN BÉRAUD

Béraud became so immersed in the city of Paris that he came to represent the very pinnacle of metropolitan life. Charming, eloquent and exquisitely dressed, after moving to the city from his native Russia and abandoning his law degree, the doors of the capital opened for him. He found himself at the centre of the glittering social scene and was calculated in rising through the ranks to become the most talked about figure in contemporary art. His paintings were the height of modernity in both style and subject, depicting everyday urban life on the streets, the seedy underbelly of the city, and the private rooms of high society, not accessible to most Parisians. This confluence of high and low society was testament to how deeply Béraud understood Paris in all of its variation, and the neutral precision of his depictions did not pass judgement against any facet of life. Béraud’s reputation has waned since his death, but the work of the man considered the most modern of artists still retains an urgency when viewed today, more than a century after its conception.

Jean Béraud

JEAN BÉRAUD, 1911. OIL ON CANVAS.

Béraud became so immersed in the city of Paris that he came to represent the very pinnacle of metropolitan life. Charming, eloquent and exquisitely dressed, after moving to the city from his native Russia and abandoning his law degree, the doors of the capital opened for him. He found himself at the centre of the glittering social scene and was calculated in rising through the ranks to become the most talked about figure in contemporary art. His paintings were the height of modernity in both style and subject, depicting everyday urban life on the streets, the seedy underbelly of the city, and the private rooms of high society, not accessible to most Parisians. This confluence of high and low society was testament to how deeply Béraud understood Paris in all of its variation, and the neutral precision of his depictions did not pass judgement against any facet of life. Béraud’s reputation has waned since his death, but the work of the man considered the most modern of artists still retains an urgency when viewed today, more than a century after its conception.

Rouen Cathedral, Morning Fog

CLAUDE MONET

Over two years, Monet painted the same facade of the Rouen Cathedral thirty different times. Viewed in their totality, these paintings capture the building from dawn to dusk, examining the changing shape of the architecture as the sun moves across it. This type of painting was not uncommon for Monet; he obsessively documented scenes over and over, trying to capture the extreme present, and would change canvases as the sun moved across the sky. His loyalty was to light and he strove to capture it as accurately as possible. Yet, his work with the Rouen Cathedral feels different, for even in it’s most clear there is an ethereality to it - the grand, circular window that seems to open like a portal into another world regardless of how the sun falls. It epitomises the relationship between painting and architecture at its best, an artist’s eye that can see in a building the infinity of its variation, can interpret the work of one craftsman to another. It forces us to refocus, not just on the Rouen Cathedral and Monet’s depictions, but on the buildings around us, and the ease at which they transform across the day.

Claude Monet

CLAUDE MONET, 1894. OIL ON CANVAS.

Over two years, Monet painted the same facade of the Rouen Cathedral thirty different times. Viewed in their totality, these paintings capture the building from dawn to dusk, examining the changing shape of the architecture as the sun moves across it. This type of painting was not uncommon for Monet; he obsessively documented scenes over and over, trying to capture the extreme present, and would change canvases as the sun moved across the sky. His loyalty was to light and he strove to capture it as accurately as possible. Yet, his work with the Rouen Cathedral feels different, for even in it’s most clear there is an ethereality to it - the grand, circular window that seems to open like a portal into another world regardless of how the sun falls. It epitomises the relationship between painting and architecture at its best, an artist’s eye that can see in a building the infinity of its variation, can interpret the work of one craftsman to another. It forces us to refocus, not just on the Rouen Cathedral and Monet’s depictions, but on the buildings around us, and the ease at which they transform across the day.

Totem

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB

Different times call for different images, so thought Adolph Gottlieb, and in the tumultuous times during and after the Second World War, the images that were need were Pictographs. Developed by Gottlieb as a way to unify his disparate interests in surrealism, geometric abstraction and native art from across the Americas, they serve as readable images that transform symbols into meaning. They are a way to translate the complications, neurosis, and chaos of modernity into something accessible to the subconscious, cutting through the noise of a difficult world with abstraction. Yet, abstraction was not a word Gottlieb liked to use, he said that “to my mind certain so-called abstraction is not abstraction at all. On the contrary, it is the realism of our time.” The symbols, neatly divided into grids, becomes figures, faces, creatures of the recesses of our mind that seem to communicate wordlessly of a world within us.

Adolph Gottlieb

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB, 1947. OIL ON CANVAS.

“The role of the artist has, of course, always been that of image maker”, said Adolph Gottlieb, “[But] different times require different images”. Gottlieb lived through many different times; born in 1903, he left school at 17 and set off for Europe to learn art on the streets of Paris. Through wars, artistic movements, upheavals and changes, Gottlieb adapted his images to reflect to times and then, in 1957, his oeuvre apexed with the start of the Blast Series, a series of works that would continue until his death in 1974. Each ‘Blast Work’ follows the same format, a circular, more ordered form on the top half of the canvas and the bottom half is inhabited by frenetic, chaotic, distressed markings of pure energy. Gottlieb saw these works as the conclusion to the central idea he had been working on throughout his life. Namely, that opposites necessarily exist together. Light exists only with dark, calm only chaos and order only with disorder – these oppositional concepts are neither exclusive nor complimentary, instead they are requisites for the others existence.

Landscape of La Gardie, near Calihau

ACHILLE LAUGÉ

A peasant boy from a small town, Laugé struggled to make it as an artist in the capital city. Moving to Paris to paint at 21 while he worked in a pharmacy to cover the bills, he was surrounded by a scene of artists changing the culture around them, but doing so from a position of some societal power. He, on the other hand, found himself isolated and without connections in the city, and when his work was exhibited in significant exhibitions alongside Bonnard, Denis, Toulouse-Lautrec and others, it was derided for it’s attempts to ‘impress’. Class prejudice seemed to surround him, and even in his artworks, inspired by the pointillist and post-impressionist styles of the day, viewers sensed this struggle for upward mobility. When his father died, Laugé returned home to the small town he was born, Caligula. He built a modest house for him and his family, and prepared himself for a simple, austere life. Yet it was back in these humble beginnings that inspiration struck anew. He constructed a studio within a horse-drawn cart and travelled the region, painting the landscapes in oil and pastel before returning to the work in his home studio. He style simplified, in match with his surroundings, and the very thing he had ran away from brought him mastery and success.

Achille Laugé

ACHILLE LAUGÉ, 1902. OIL ON CANVAS.

A peasant boy from a small town, Laugé struggled to make it as an artist in the capital city. Moving to Paris to paint at 21 while he worked in a pharmacy to cover the bills, he was surrounded by a scene of artists changing the culture around them, but doing so from a position of some societal power. He, on the other hand, found himself isolated and without connections in the city, and when his work was exhibited in significant exhibitions alongside Bonnard, Denis, Toulouse-Lautrec and others, it was derided for it’s attempts to ‘impress’. Class prejudice seemed to surround him, and even in his artworks, inspired by the pointillist and post-impressionist styles of the day, viewers sensed this struggle for upward mobility. When his father died, Laugé returned home to the small town he was born, Caligula. He built a modest house for him and his family, and prepared himself for a simple, austere life. Yet it was back in these humble beginnings that inspiration struck anew. He constructed a studio within a horse-drawn cart and travelled the region, painting the landscapes in oil and pastel before returning to the work in his home studio. He style simplified, in match with his surroundings, and the very thing he had ran away from brought him mastery and success.

Snowy Landscape

CUNO AMIET

A monumental canvas of more than four square metres has the majority of its bulk dedicated to the infinitesimal small variations of white on a snowy day. The figure, a long skier who traverses the length of the artwork in a desperate attempt to reach its end, is comically small with the bulk of colour behind dwarfing him. The work is deeply unusual, all the more so for the fact it was painted at the turn of the century. The modern viewer, after a near century of artists such as Rauschenberg, Malevich, Ryman and others creating all white canvases, may be used to the starkness of this work, but Amiet predates even the earliest of these by some fifteen years. The work is presented as a landscape, but it becomes about the insignificance of man in the face of nature, the perseverance of the human spirit and, perhaps most simply, of the effect of colour. Amiet never achieved major success in his life, and has remained undeservedly unknown today. His work was, perhaps, so ahead of his time, so singular that he was destined to remain of the fringe of a world he anticipated before so many others.

Cuno Amiet

CUNO AMIET, 1904. OIL ON CANVAS.

A monumental canvas of more than four square metres has the majority of its bulk dedicated to the infinitesimal small variations of white on a snowy day. The figure, a long skier who traverses the length of the artwork in a desperate attempt to reach its end, is comically small with the bulk of colour behind dwarfing him. The work is deeply unusual, all the more so for the fact it was painted at the turn of the century. The modern viewer, after a near century of artists such as Rauschenberg, Malevich, Ryman and others creating all white canvases, may be used to the starkness of this work, but Amiet predates even the earliest of these by some fifteen years. The work is presented as a landscape, but it becomes about the insignificance of man in the face of nature, the perseverance of the human spirit and, perhaps most simply, of the effect of colour. Amiet never achieved major success in his life, and has remained undeservedly unknown today. His work was, perhaps, so ahead of his time, so singular that he was destined to remain of the fringe of a world he anticipated before so many others.

Dancing Soldiers

MIKHAIL LARIONOV

As one moves further from the epicentre of a movement, the ideas begin to distort. Concepts are reinterpreted in a game of geographic Chinese whispers and stylistic elements merge with local traditions into something altogether different. Such is the case with Mikhail Larionov’s work, painted in Russia but indebted to and inspired by the fauvist movement happening simultaneously in Paris. Combining a bright palette and loose dimensionality of the French avant-garde with the icon paintings of Russian history and traditional styles of woodcut illustration, the work is able to speak across time and place. Larionov named his style Neo-Primitivism, a combination of the old and the new that saw the past not as a distant land but a living collaborator in the present. Larionov would eventually leave Russia to live in Paris where he ingratiated himself to the very artists who’s style he had made his own, and there his paintings became more technically refined. Yet it is his early work, while still in his native land, that stands above, the gentle naivety combines with a contemporary understanding and art historical knowledge to create playful works of poignancy.

Mikhail Larionov

MIKHAIL LARIONOV, 1909. OIL ON CANVAS.

As one moves further from the epicentre of a movement, the ideas begin to distort. Concepts are reinterpreted in a game of geographic Chinese whispers and stylistic elements merge with local traditions into something altogether different. Such is the case with Mikhail Larionov’s work, painted in Russia but indebted to and inspired by the fauvist movement happening simultaneously in Paris. Combining a bright palette and loose dimensionality of the French avant-garde with the icon paintings of Russian history and traditional styles of woodcut illustration, the work is able to speak across time and place. Larionov named his style Neo-Primitivism, a combination of the old and the new that saw the past not as a distant land but a living collaborator in the present. Larionov would eventually leave Russia to live in Paris where he ingratiated himself to the very artists who’s style he had made his own, and there his paintings became more technically refined. Yet it is his early work, while still in his native land, that stands above, the gentle naivety combines with a contemporary understanding and art historical knowledge to create playful works of poignancy.

Vertigo of the Hero

ANDRÉ MASSON

In a long life, Masson made time for everything. A pioneering surrealist, he was the most willing adopter of automatism, or the process of automatic drawing where the hand is allowed to run unchained on the canvas with no conscious decisions affecting its movement. He pushed these ideas further still, scattering sand or mud onto a surface and letting the organic shapes it feel in guide the direction of his work. A young rebel of Surrealism, he plumbed the depths of his subconscious until he, reaching the bottom, sought out structure once again. By the end of the war, having survived active duty and sharing a studio with Joan Míro, he abandoned the Surrealists and his work became structured, often depicting scenes of violence or eroticism. Condemned by obscenity laws under Nazi rule, he fled to America where he became a fatherly figure to the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist movement, until he returned to France to paint landscapes. In the evening of his life, he returned to a less disciplined form, retaining parts of all he had learned to produce moving, erotic works of the subconscious mind.

André Masson

ANDRÉ MASSON, 1974. PASTEL ON PAPER.

In a long life, Masson made time for everything. A pioneering surrealist, he was the most willing adopter of automatism, or the process of automatic drawing where the hand is allowed to run unchained on the canvas with no conscious decisions affecting its movement. He pushed these ideas further still, scattering sand or mud onto a surface and letting the organic shapes it feel in guide the direction of his work. A young rebel of Surrealism, he plumbed the depths of his subconscious until he, reaching the bottom, sought out structure once again. By the end of the war, having survived active duty and sharing a studio with Joan Míro, he abandoned the Surrealists and his work became structured, often depicting scenes of violence or eroticism. Condemned by obscenity laws under Nazi rule, he fled to America where he became a fatherly figure to the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist movement, until he returned to France to paint landscapes. In the evening of his life, he returned to a less disciplined form, retaining parts of all he had learned to produce moving, erotic works of the subconscious mind.

Le Christ Vert

MAURICE DENIS

As a child, Maurice Denis had only two passions – religion and art. It seemed clear to him that his path was to combine the two, to follow in the footsteps of the great Renaissance monk-cum-artist Fra Angelo and make religious art that elevated the holy in the minds of men. Yet, before this work was painted he was in a period of deep questioning, having co-founded the Nabi group the same year he found himself surrounded by the decadence and debauchery of the artists studio, and reluctantly drawn to it. Art and religion seemed, for the first time in his life, at odds with each other and it was only in the process of creating this work, and others in the series, that he unified the Cloister and the Studio in his mind. “I believe”, he said, “that art must sanctify nature; I believe that vision without the Spirt is vain; and it is the mission of the aesthete to erect beautiful things into immutable icons”.

Maurice Denis

MAURICE DENIS, 1890. OIL ON CANVAS.

As a child, Maurice Denis had only two passions – religion and art. It seemed clear to him that his path was to combine the two, to follow in the footsteps of the great Renaissance monk-cum-artist Fra Angelo and make religious art that elevated the holy in the minds of men. Yet, before this work was painted he was in a period of deep questioning, having co-founded the Nabi group the same year he found himself surrounded by the decadence and debauchery of the artists studio, and reluctantly drawn to it. Art and religion seemed, for the first time in his life, at odds with each other and it was only in the process of creating this work, and others in the series, that he unified the Cloister and the Studio in his mind. “I believe”, he said, “that art must sanctify nature; I believe that vision without the Spirt is vain; and it is the mission of the aesthete to erect beautiful things into immutable icons”.

Face

WOLFGANG PAALEN

As Europe was moving towards representative art under the Surrealist guidance of André Breton, a counter-insurgency was brewing. In their shared city of Paris, a group of artists that included Paalen formed Abstraction-Creation as a rebellion against the surrealist style that was dominating the cultural epoch. It embraced the entire field of abstract art amongst it’s many members, but prioritised the austere; geometric forms, mathematical compositions and reductively elegant shapes stood proudly in the face of the figurative subconscious. Yet Paalen, like many other members of the group, eventually succumbed to the allure of Surrealism and became a fully fledged member of the group. It was only once part of it’s fabric did he truly understand what it was he had rebelled against in the first place, finding the pseudo-religious, obsessively interior motifs of the surrealists as an insufficient way to true spirituality and enlightenment. He abandoned the group and spent years in exile in Mexico, pioneering a new, uniquely Paalen form of art that combined ideas of quantum theory with totemism, psycho-analysis and Marxist critique.

Wolfgang Paalen

WOLFGANG PAALEN, 1946. OIL ON CANVAS.

As Europe was moving towards representative art under the Surrealist guidance of André Breton, a counter-insurgency was brewing. In their shared city of Paris, a group of artists that included Paalen formed Abstraction-Creation as a rebellion against the surrealist style that was dominating the cultural epoch. It embraced the entire field of abstract art amongst it’s many members, but prioritised the austere; geometric forms, mathematical compositions and reductively elegant shapes stood proudly in the face of the figurative subconscious. Yet Paalen, like many other members of the group, eventually succumbed to the allure of Surrealism and became a fully fledged member of the group. It was only once part of it’s fabric did he truly understand what it was he had rebelled against in the first place, finding the pseudo-religious, obsessively interior motifs of the surrealists as an insufficient way to true spirituality and enlightenment. He abandoned the group and spent years in exile in Mexico, pioneering a new, uniquely Paalen form of art that combined ideas of quantum theory with totemism, psycho-analysis and Marxist critique.

Leda and the Swan

PAUL CÉZANNE

In Metamorphoses by Ovid, amongst the greatest of the Roman poets, the story of Leda and the swan is one of consensual eroticism. This is at odds with other accounts of the myth, where the level of consent in the relationship differs wildly, though all see Zeus take the shape of a swan and have sexual relations with Leda that result in children. Yet it was Ovid’s telling that took up favour in the Renaissance. This was not least because the depiction of erotic acts between humans was firmly forbidden and so the Roman story was a suitable vehicle for artists to express a human sexuality otherwise forbidden by the church. Cézanne, some centuries removed from this vogue, choses the same subject matter and for much the same reason. The most explicitly erotic paintings of his oeuvre, his rendering of Leda and the Swan is overtly sensual, with Leda’s hips turned towards the viewer and the swan wrapping around her wrist as his wings rise. Yet the painting speaks to classicism, and its eroticism is well dressed in a literary academia and rich in aesthetic value, Cézanne’s loose brushstrokes and subtle colours bringing a melancholy, erotic beauty to the scene that, nonetheless, feels a weight of historical context.

Paul Cézanne

PAUL CÉZANNE, c.1880. OIL ON CANVAS.

In Metamorphoses by Ovid, amongst the greatest of the Roman poets, the story of Leda and the swan is one of consensual eroticism. This is at odds with other accounts of the myth, where the level of consent in the relationship differs wildly, though all see Zeus take the shape of a swan and have sexual relations with Leda that result in children. Yet it was Ovid’s telling that took up favour in the Renaissance. This was not least because the depiction of erotic acts between humans was firmly forbidden and so the Roman story was a suitable vehicle for artists to express a human sexuality otherwise forbidden by the church. Cézanne, some centuries removed from this vogue, choses the same subject matter and for much the same reason. The most explicitly erotic paintings of his oeuvre, his rendering of Leda and the Swan is overtly sensual, with Leda’s hips turned towards the viewer and the swan wrapping around her wrist as his wings rise. Yet the painting speaks to classicism, and its eroticism is well dressed in a literary academia and rich in aesthetic value, Cézanne’s loose brushstrokes and subtle colours bringing a melancholy, erotic beauty to the scene that, nonetheless, feels a weight of historical context.

Head of a Woman

PABLO PICASSO

‘The masks weren’t like other kinds of sculptures’, said Picasso when talking about the African art that influenced and inspired him, ‘they were magical things’. It was this implacable power that most informed him, above any sense of visual order or identity, it was the way in which the masks pointed to a higher level of existence and seemed to understand the totality of humanity in all of its contradictions. So much of the earth-shaking revolution that Picasso would bring to the art world started out of this aspirational influence. As he further developed Cubism alongside Braque, for this is a particularly early work of the movement, the multiplicity of perspectives would get larger, more overt and more severe, but they all strove for the same goal that the African masks did almost effortlessly – capture the truth that life can never be truly seen from one perspective.

Pablo Picasso

PABLO PICASSO, 1907. OIL ON CANVAS.

‘The masks weren’t like other kinds of sculptures’, said Picasso when talking about the African art that influenced and inspired him, ‘they were magical things’. It was this implacable power that most informed him, above any sense of visual order or identity, it was the way in which the masks pointed to a higher level of existence and seemed to understand the totality of humanity in all of its contradictions. So much of the earth-shaking revolution that Picasso would bring to the art world started out of this aspirational influence. As he further developed Cubism alongside Braque, for this is a particularly early work of the movement, the multiplicity of perspectives would get larger, more overt and more severe, but they all strove for the same goal that the African masks did almost effortlessly – capture the truth that life can never be truly seen from one perspective.

Group of Trees

CHAIM SOUTINE

As German bombs fell on Paris, artists scattered to safety. Soutine, Amadeo Modigliani, and their dealer Leopold Zborowski fled to the south of France where they stayed for three years in the small town of Céret, a sharp contrast to the metropolitan life they had been used to in the capital. But the town proved invigorating for the group, and Soutine executed a series of turbulent landscapes that are at once beautiful and fearful, reflecting his exiled state and the prevalent sadness of the ensuing war. Violence seeps into every brushstroke and landscapes of the pastoral, rolling hills and thick woodlands come alive with a feeling of war. Here, a group of trees obscuring a town in the distance curl up like flames, moving with erratic freedom that engulfs the surrounding landscape. Background and foreground collapse into one as the view seems to morph into torment. In retreat, Soutine found peace in the land but none in his mind and his art reflected this duality, creating some of the most disquieting works of his career and showing how the pains of war seep into everything.

Chaim Soutine

CHAIM SOUTINE, c.1922. OIL ON CANVAS.

As German bombs fell on Paris, artists scattered to safety. Soutine, Amadeo Modigliani, and their dealer Leopold Zborowski fled to the south of France where they stayed for three years in the small town of Céret, a sharp contrast to the metropolitan life they had been used to in the capital. But the town proved invigorating for the group, and Soutine executed a series of turbulent landscapes that are at once beautiful and fearful, reflecting his exiled state and the prevalent sadness of the ensuing war. Violence seeps into every brushstroke and landscapes of the pastoral, rolling hills and thick woodlands come alive with a feeling of war. Here, a group of trees obscuring a town in the distance curl up like flames, moving with erratic freedom that engulfs the surrounding landscape. Background and foreground collapse into one as the view seems to morph into torment. In retreat, Soutine found peace in the land but none in his mind and his art reflected this duality, creating some of the most disquieting works of his career and showing how the pains of war seep into everything.

The Apparition

GUSTAVE MOREAU

Salome danced for King Herod, and was rewarded with any gift that her heart desired. Spurred by her mother, who harboured open resentment towards John the Baptist for his public reprove of her marriage to the king, Salome requested the head of the imprisoned prophet. Herod, regretful but true to his word, obliged. The story appears twice in the bible, though Salome remains unnamed in both, and it became a subject of desire, obsession and inspiration for hundreds of artists through the renaissance to modernity who depicted Salome and the scene in paint, stone and pencil. None, however, were quite like Moreau’s. In a setting of pure, indulgent opulence, where both the background and the figures are adorned in ornamentation and luxury, John’s head appears not on a platter but as an apparition, floating in a halo of light and gold as thick, rich blood drips from his neck. It is a deeply surreal scene, both erotic and disturbing in which we cannot know whether the apparition is a shared hallucination, a real appearance or purely the vision of Salome herself.

Gustave Moreau

GUSTAVE MOREAU, 1876. WATERCOLOR.

Salome danced for King Herod, and was rewarded with any gift that her heart desired. Spurred by her mother, who harboured open resentment towards John the Baptist for his public reprove of her marriage to the king, Salome requested the head of the imprisoned prophet. Herod, regretful but true to his word, obliged. The story appears twice in the bible, though Salome remains unnamed in both, and it became a subject of desire, obsession and inspiration for hundreds of artists through the renaissance to modernity who depicted Salome and the scene in paint, stone and pencil. None, however, were quite like Moreau’s. In a setting of pure, indulgent opulence, where both the background and the figures are adorned in ornamentation and luxury, John’s head appears not on a platter but as an apparition, floating in a halo of light and gold as thick, rich blood drips from his neck. It is a deeply surreal scene, both erotic and disturbing in which we cannot know whether the apparition is a shared hallucination, a real appearance or purely the vision of Salome herself.

All Directions

MARK TOBEY

A mystic of the west coast and sage of Seattle, the paintings speak of a metaphysical oneness that can be achieved through art, faith and creation. Mark Tobey’s work cannot be understood outside of his prescription to the Baháʼí Faith, a spiritual religion that believes in the unity of all people outside of faith, nationality, race, or sex. All major religions are unified in their core beliefs, according to Bahá’i, but divergent in their social practices and interpretations and the world can only be prosperous when these groups come together. Tobey took up this faith in the early 1900s while travelling across Japan and China, where he also learnt traditional calligraphy and brushstroke styles. He pioneered ‘all-over’ painting, where the artwork is removed from the confines or composition and each inch is as valuable as the next, with no centre of information anywhere. Predating Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists who were deeply inspired by Tobey, his works reward deep looking that enters you into a world of remarkable peacefulness.

Mark Tobey

MARK TOBEY, 1957. TEMPERA ON PAPER.

A mystic of the west coast and sage of Seattle, the paintings speak of a metaphysical oneness that can be achieved through art, faith and creation. Mark Tobey’s work cannot be understood outside of his prescription to the Baháʼí Faith, a spiritual religion that believes in the unity of all people outside of faith, nationality, race, or sex. All major religions are unified in their core beliefs, according to Bahá’i, but divergent in their social practices and interpretations and the world can only be prosperous when these groups come together. Tobey took up this faith in the early 1900s while travelling across Japan and China, where he also learnt traditional calligraphy and brushstroke styles. He pioneered ‘all-over’ painting, where the artwork is removed from the confines or composition and each inch is as valuable as the next, with no centre of information anywhere. Predating Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists who were deeply inspired by Tobey, his works reward deep looking that enters you into a world of remarkable peacefulness.