From Cynicism to Sincerity (Part II)

To read part one of Noah Gabriel Martin’s ‘From Cynicism to Sincerity’, click here.

Noah Gabriel Martin February 10, 2026

I dropped the slacker voice when I left Canada, but I get sucked right back into it when I’m home for a visit. It doesn’t happen all the time, but it always happens with certain people: people who I don’t feel all that comfortable with; people who I don’t know how to communicate with. Mostly, I fall back into the voice when talking to men.

In general, falling intonation in English denotes a statement, and so there’s nothing especially gendered about its use to mark the termination of a phrase. But linguists have noted that men emphasise it.

If exaggerated downward inflection is more associated with men’s speech now, when it has come to signal ironic detachment, maybe that’s because it serves a useful purpose in helping men avoid vulnerability. Specifically, the vulnerability that comes with sincerity, or putting your heart on the line - a vulnerability that can be perilous for men.

I noticed the slacker voice only after it had gone, during episodes of what How I Met Your Mother coined ‘revertigo,’ a reversion to old character traits when associating with places or figures from it. In England, my voice had become higher and lost that drop in pitch. When I was reverting I was painfully aware that I was doing it, yet totally unable to pull myself out of it.

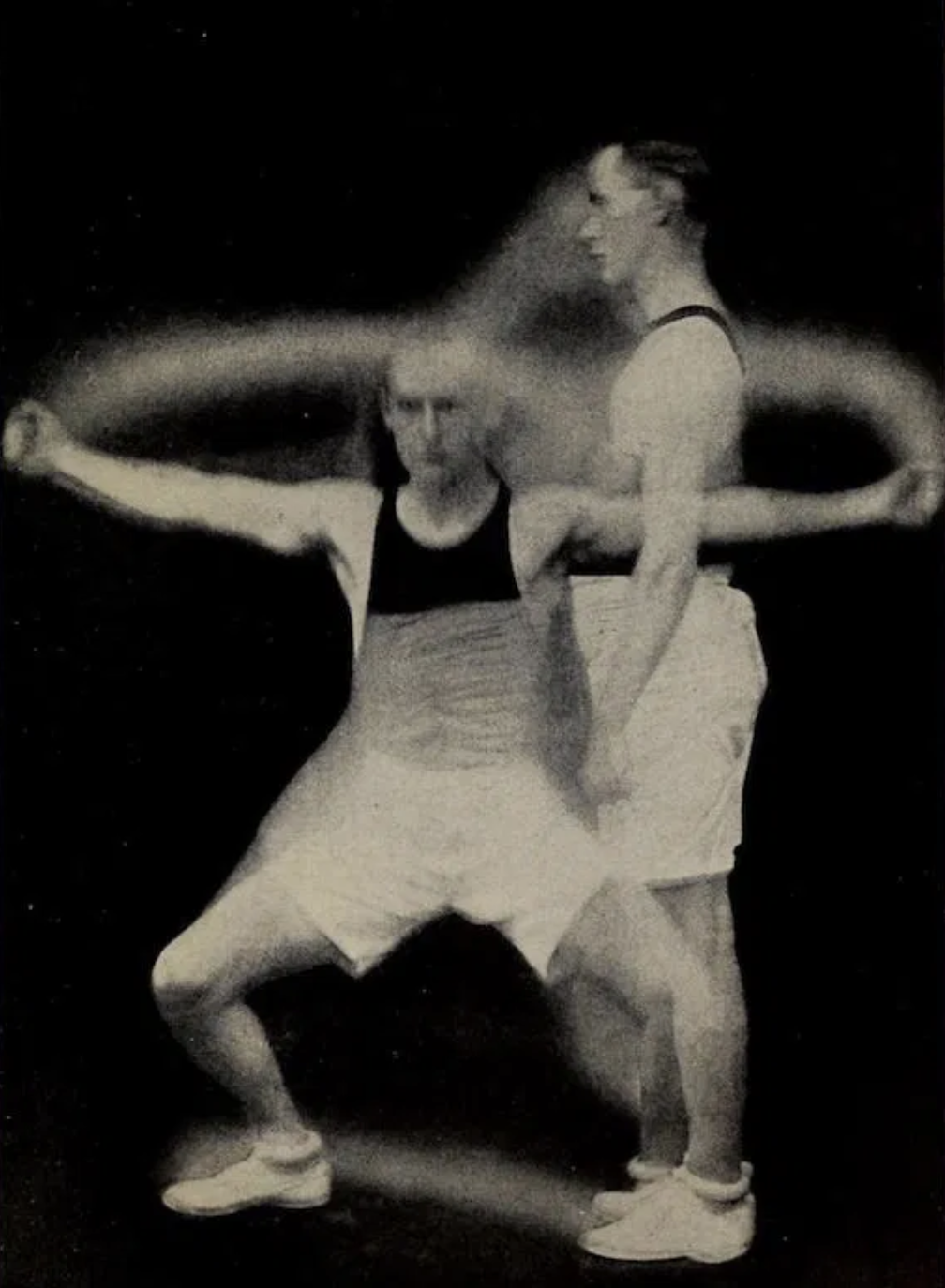

This old voice felt strained. My new voice felt more natural, more like my own—not just because speech came more easily, but because it allowed me to express more of myself. Without the constraint of that exaggerated ‘final lowering’ I could have so much more fun with the dynamics of a sentence. Like any armour, the blankness of my old voice weighed me down and inhibited my movement.

I first started to wonder about the etiology and teleology of the voice during a hiking trip last Summer. The revertigo reached its peak when for 6 straight (very straight) days I shared the company of the most closed-off group of guys I’ve encountered in a decade. I didn’t know them well, and they made no effort to strike up a conversation. Meanwhile each of my ouvertures fell to the forest floor with a monosyllabic splat.

I didn’t mind. I was there to hike. I was happy to remain silent, and after making an effort for the first day, that’s pretty much what I did. Maybe they preferred it that way, but I didn’t think so - I got the impression they just didn’t know how to do anything else. Meanwhile, any time I did open my mouth, everything came out as a low mutter, flatter than a pancake.

That’s when I started to suspect a connection between the voice’s performed apathy, the terror of vulnerability, and being a man.

Men’s terror of vulnerability is a consequence of being terrorised. In her book on how patriarchy damages men, bell hooks describes the controlling, demeaning and violent treatment boys are subjected to by their fathers, mothers, and peers.

This terrorism targets, above all else, vulnerability, whether that’s the vulnerability of expressing emotion, or of displaying affection - it targets anything that makes a boy vulnerable to being hurt.

“In trying to make a man invulnerable, patriarchal terror instead does something quite different - it produces a terror of vulnerability.”

The cruel elegance of patriarchal terrorism against boys is that the target and the weapon are the same - hurt. The point is to make a boy into a man that can’t be hurt, and so anything that might hurt a boy is both a legitimate and an effective target for terrorism.

That’s why the most familiar advice given to boys getting bullied is to not let them see you cry; as long as the punishment doesn’t hurt you anymore, you’re no longer an effective target. But this also reveals that the advice is complicit with the bullying. It is not strategic, even if it may look like it; it doesn’t propose a way to defeat the bully. It’s merely an instruction for what’s expected of the victim, an instruction on how to surrender. It’s not just that you’re no longer an effective target, it’s also that you’re no longer a legitimate target: the terrorism has successfully transformed you into a man not vulnerable to patriarchal violence anymore, and, more than likely, a man capable of going on to perpetrate that violence himself.

Because vulnerability is itself the target, any kind of vulnerability is just as likely to make a boy victim to it. It doesn’t matter whether it’s something a man really should remain vulnerable to, or something worth growing out of. Displaying emotions indicates vulnerability, just as showing that you care does, or even revealing too much about how you make up your mind.

As Terrence Real writes in How Can I Get Through To You? “Our sons learn the code early and well; don’t cry, don’t be vulnerable, don’t show weakness—ultimately, don’t show that you care.”

I learned as a boy that if I let you know what I’m enthusiastic about, you can mock me for it because it’s stupid and uncool, and that if I show you affection, you can punish me for it by rejecting me and proving to me that I’m unworthy of reciprocating it. In trying to make a man invulnerable, patriarchal terror instead does something quite different - it produces a terror of vulnerability. It does this just because it can’t make a man invulnerable, and because a man will always remain vulnerable, the terror of vulnerability has plenty of fuel.

The terrorisation of vulnerability in boys is sufficient to explain adult male behaviour that avoids all vulnerability. It explains the masculine reserve that refuses to share its enthusiasms and pain, to show affection, or to ask for it.

That terrorization would explain why my fellow hikers were so withdrawn.

This also explains the Simpsons’ snark, and it would explain why the voice of my generation was a voice that must never take anything seriously, and must always maintain ironic distance from whatever it says. It was a voice terrified of believing in something, and what might happen if someone said what it believed in was stupid.

I miss The Simpsons. I miss the period of my life when everything was a joke and the point of saying anything wasn’t that it was true or that it mattered, but just that it was clever. But I love the voice I have now. I don’t mean the way it sounds, I love what it can do. I love the way it rises and falls; its expressive range; how its sincerity can, like open hands, lift up the things worth saying; and the way it can whisper ‘I love you’ with all the openness to a beloved and a world outside of what I can use my words to control that those words need to really be true.

Dr. Noah Gabriel Martin lectures in philosophy at the University of Winchester and runs the College of Modern Anxiety, a social enterprise that promotes lifelong learning for liberation. He recently began to study dance, which has taught him a lot about being an absolute beginner.