Girl in an Interior

VUILLARD

Édouard Vuillard was part of a secret society of artists known as ‘The Nabis’, who saw their role as to move art away from naturalist Impressionism into a synthesis of metaphors and symbols that more accurately represented perception, if not reality. The group had disbanded by the time this work was created, and Vuillard had been painting realistic interiors, mostly of women in their home. Yet beneath the surface of these seemingly straightforward works we can see the influence of his avant garde origins. An obsessive studier of objects, everything he painted held relevance to the sitter, with each object acting as a metaphor for a facet of their personality, and he drew a connection between the interiors of the home and the interior of his sitter. He did not see these works as portraits, but as stolen moments that extended beyond the subject and came to represent society at large.

ÉDOUARD VUILLARD

ÉDOUARD VUILLARD, 1910. OIL ON BOARD.

Édouard Vuillard was part of a secret society of artists known as ‘The Nabis’, who saw their role as to move art away from naturalist Impressionism into a synthesis of metaphors and symbols that more accurately represented perception, if not reality. The group had disbanded by the time this work was created, and Vuillard had been painting realistic interiors, mostly of women in their home. Yet beneath the surface of these seemingly straightforward works we can see the influence of his avant garde origins. An obsessive studier of objects, everything he painted held relevance to the sitter, with each object acting as a metaphor for a facet of their personality, and he drew a connection between the interiors of the home and the interior of his sitter. He did not see these works as portraits, but as stolen moments that extended beyond the subject and came to represent society at large.

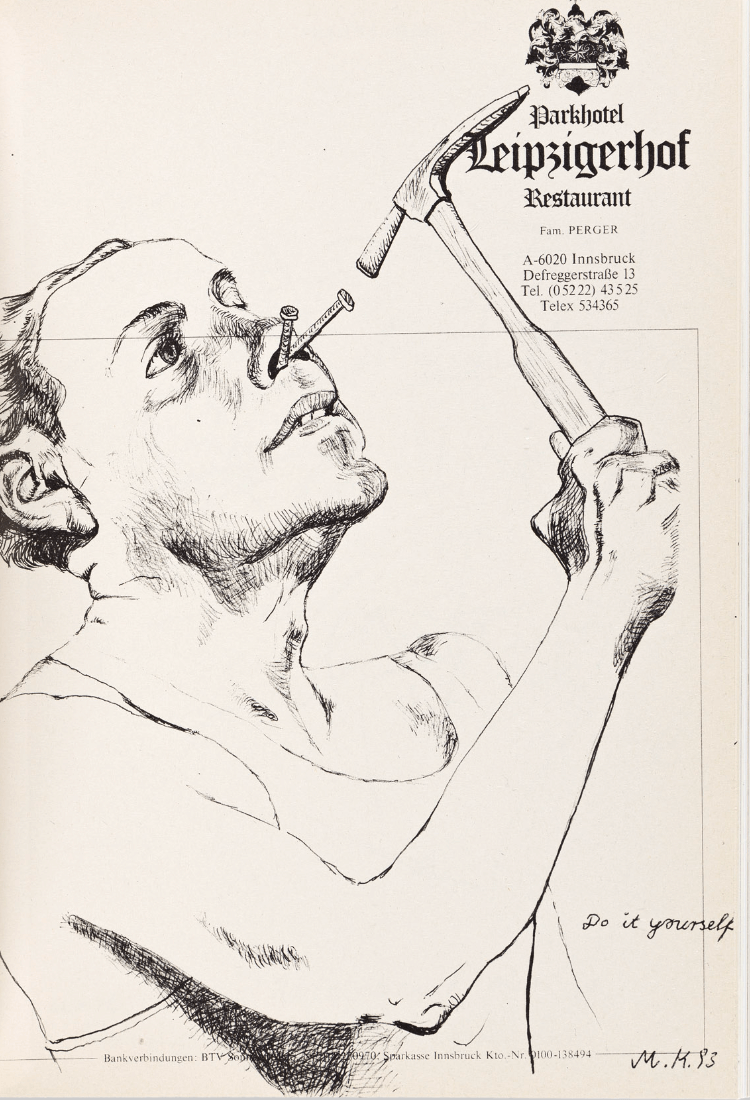

Hotel Drawings

KIPPENBERGER

Kippenberger let the stationary guide him. Over the course of his short life, he drew hundreds of works on Hotel Notecards he collected on his travels, often from hotels he never stayed in. Exceeding their origin as preparatory sketches for wider works, the hotel drawings became a constant source of reflection, almost diaristic in nature. Kippenberger drew self portraits from that day, surrealist renderings of his emotional state. He drew Frank Sinatra, scientists, graphic posters, cartoons, the hotels themselves, but while they are frenetic in their multitude, each taken alone offers a surprising calm. A staggering technical ability is evident, and a breadth of style remarkable, the story of the letterheads, and of a rambunctious, nomadic life that it tells, is offset but a profound sense of self, and of calmness within that self.

MARTIN KIPPENBERGER

MARTIN KIPPENBERGER, 1995

Kippenberger let the stationary guide him. Over the course of his short life, he drew hundreds of works on Hotel Notecards he collected on his travels, often from hotels he never stayed in. Exceeding their origin as preparatory sketches for wider works, the hotel drawings became a constant source of reflection, almost diaristic in nature. Kippenberger drew self portraits from that day, surrealist renderings of his emotional state. He drew Frank Sinatra, scientists, graphic posters, cartoons, the hotels themselves, but while they are frenetic in their multitude, each taken alone offers a surprising calm. A staggering technical ability is evident, and a breadth of style remarkable, the story of the letterheads, and of a rambunctious, nomadic life that it tells, is offset but a profound sense of self, and of calmness within that self.

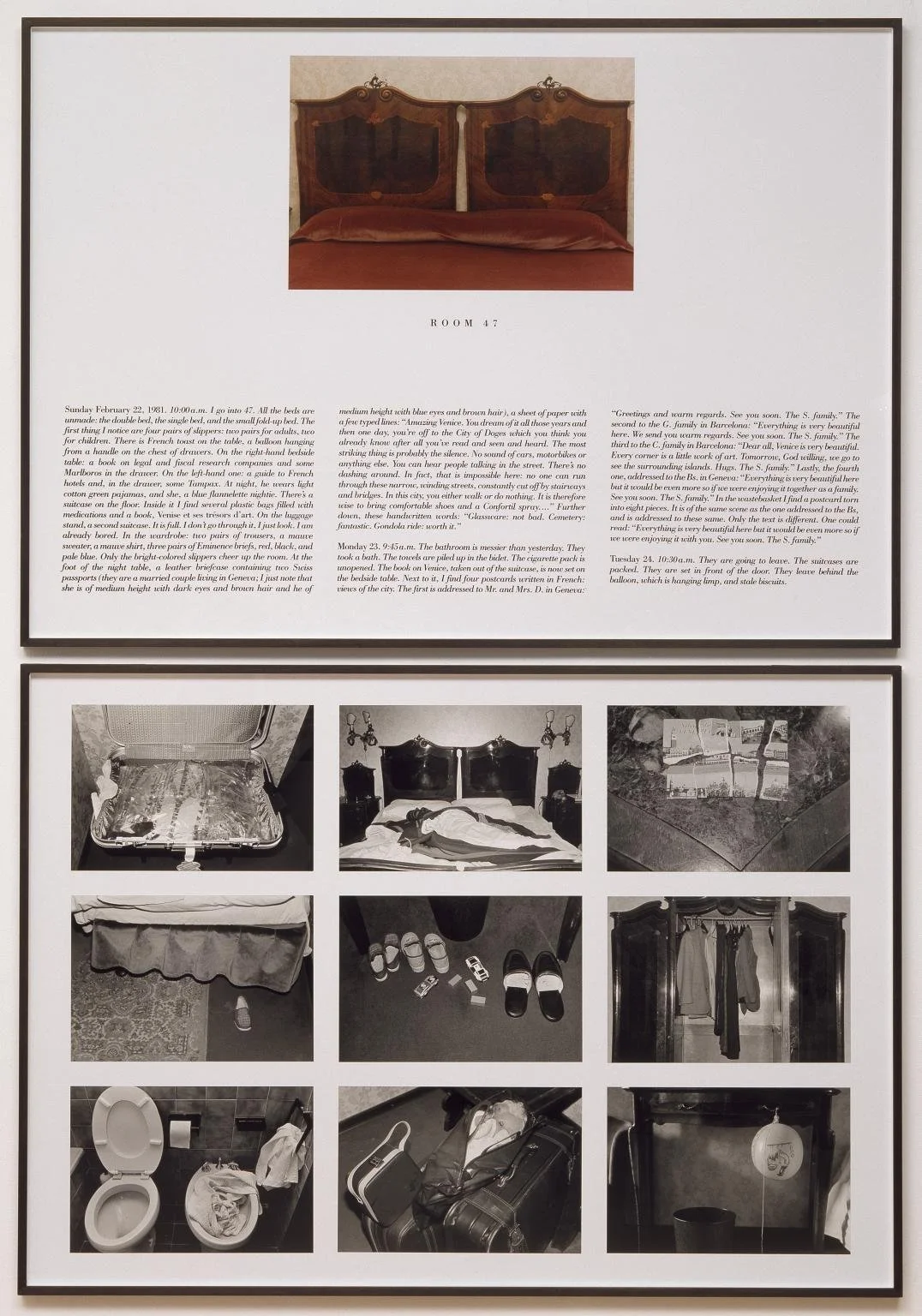

The Hotel, Room 47

CALLE

In February 1981, the conceptual artist Sophie Calle was hired as a chambermaid at a Venetian hotel. As she cleaned each of the twelve rooms, she not only documented the belongings of the guests but, in some way, became them. She used their perfumes, the contents of their make up bags, ate their leftover food, tried on their clothes. She rummaged through suitcases and read diaries. In Room 47, a family of four was staying. They bored her. Her unashamed voyeurism sought something more, something different. The resulting artworks appear as diptychs. One frame contains Calle’s written observations not only of the contents of their rooms but of details of their lives, parsed from the detritus. How much can we learn from the contents of someone’s suitcase, and how much can we become them from fleeting impersonations?

SOPHIE CALLE

SOPHIE CALLE, 1981

In February 1981, the conceptual artist Sophie Calle was hired as a chambermaid at a Venetian hotel. As she cleaned each of the twelve rooms, she not only documented the belongings of the guests but, in some way, became them. She used their perfumes, the contents of their make up bags, ate their leftover food, tried on their clothes. She rummaged through suitcases and read diaries. In Room 47, a family of four was staying. They bored her. Her unashamed voyeurism sought something more, something different. The resulting artworks appear as diptychs. One frame contains Calle’s written observations not only of the contents of their rooms but of details of their lives, parsed from the detritus. How much can we learn from the contents of someone’s suitcase, and how much can we become them from fleeting impersonations?

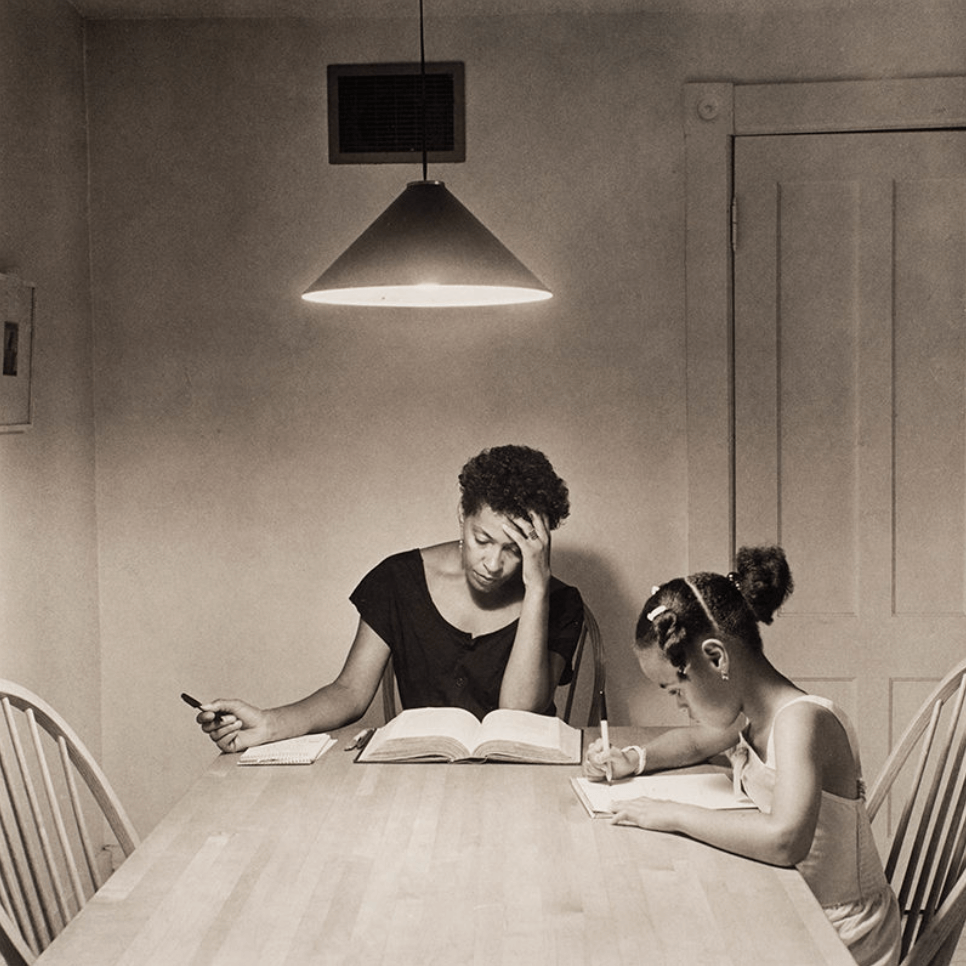

Kitchen Table Series

WEEMS

Radically simple, Carrie Mae Weems’ portraits, known as the Kitchen Table Series, offer a picture of universality. In 1989, Weems began setting up her camera at the end of the kitchen table, a single hanging light and a door frame behind her the only other decoration. Over the next year, she took portraits of a fictional life, a romance leading to a break-up, sadness leading to contentment. Within her four walls, it is hard not to see our own. The minutiae and mundanity of everyday existence becomes something profound and palpable in Weems’ images. As she says, ‘This woman can stand in for me and for you; she can stand in for the audience, she leads you into history. She’s a witness and a guide.’

CARRIE MAE WEEMS

CARRIE MAE WEEMS, 1990

Radically simple, Carrie Mae Weems’ portraits, known as the Kitchen Table Series, offer a picture of universality. In 1989, Weems began setting up her camera at the end of the kitchen table, a single hanging light and a door frame behind her the only other decoration. Over the next year, she took portraits of a fictional life, a romance leading to a break-up, sadness leading to contentment. Within her four walls, it is hard not to see our own. The minutiae and mundanity of everyday existence becomes something profound and palpable in Weems’ images. As she says, ‘This woman can stand in for me and for you; she can stand in for the audience, she leads you into history. She’s a witness and a guide.’

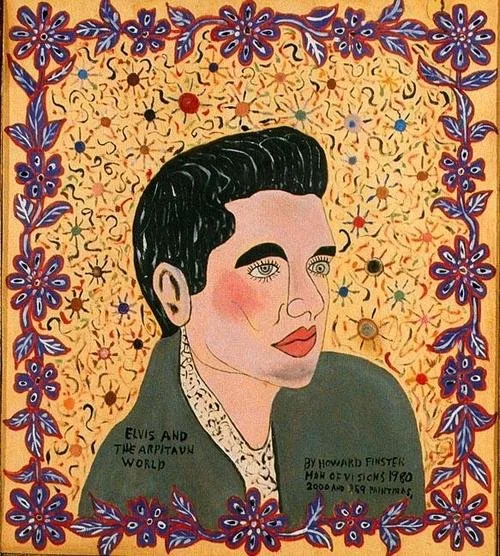

Elvis and the Arpitaun World

FINSTER

A folk artist with visions from God. Finster paints with an untrained hand and creates something closer to the truth than training can give you. Reminiscent of Giotto, his flat planes democratise the world he exhibits. Elvis becomes a religious icon, existing on the same dimension as the organic forms that dance around him like a halo. Finster used figures from culture repeatedly, warping perspectives of time and place to draw allusions between the holy world and the one he lived in. For Finster, anything could be religious, and art was the vehicle to explore it. He believed God asked him paint 5000 works, and he far exceeded this call.

HOWARD FINSTER

HOWARD FINSTER, 1980

A folk artist with visions from God, Finster paints with an untrained hand and creates something closer to the truth than training can give you. Reminiscent of Giotto, his flat planes democratise the world he exhibits. Elvis becomes a religious icon, existing on the same dimension as the organic forms that dance around him like a halo. Finster used figures from culture repeatedly, warping perspectives of time and place to draw allusions between the holy world and the one he lived in. For Finster, anything could be religious, and art was the vehicle to explore it. He believed God asked him to paint 5000 works, and he far exceeded this call.

The Ghent Altarpiece, or Adoration of the Mystic Lamb

VAN EYCK

Hubert and Jan Van Eyck heralded the artistic end of the Middle Ages and the Ghent Altarpiece is their crowning achievement. A work of staggering, exacting beauty — it is reverent in its portrayal of divinity while still grounding itself in earthly presence. This marked a departure from the overarching symbolism and flat, matter-of-fact compositions of the work that came before. Instead, the Van Eycks championed observation of nature and human representation as a means to approach holiness, focusing the attention of the religious pilgrim to himself and his place on earth, as opposed to the idealisation of Christian spirituality. God sits above, centred, in royal garb, flanked on either side by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist. Angels play heavenly music and Adam and Eve complete the edges of the upper row. Below, scenes of pastoral prayer play out, watched over by the dove of the Holy Spirit. The human, mortal world literally holds up divinity. It was a radical suggestion — that the everyman is not just worthy of representation but is necessary in the story of God, though the hierarchy is clear. It is generally accepted that, after Hubert’s death in 1426, the younger Jan van Eyck took up his stead and completed the painting, when it was then displayed in St. Bavo’s Cathedral where some 600 years later it still stands today. It is amongst the important pieces of Western art ever created, laying the foundations for the Renaissance and changing the very world it sought to represent.

HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK

HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK, c.1432. OIL PAINT AND TEMPERA ON WOOD.

Hubert and Jan Van Eyck heralded the artistic end of the Middle Ages and the Ghent Altarpiece is their crowning achievement. A work of staggering, exacting beauty — it is reverent in its portrayal of divinity while still grounding itself in earthly presence. This marked a departure from the overarching symbolism and flat, matter-of-fact compositions of the work that came before. Instead, the Van Eycks championed observation of nature and human representation as a means to approach holiness, focusing the attention of the religious pilgrim to himself and his place on earth, as opposed to the idealisation of Christian spirituality. God sits above, centred, in royal garb, flanked on either side by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist. Angels play heavenly music and Adam and Eve complete the edges of the upper row. Below, scenes of pastoral prayer play out, watched over by the dove of the Holy Spirit. The human, mortal world literally holds up divinity. It was a radical suggestion — that the everyman is not just worthy of representation but is necessary in the story of God, though the hierarchy is clear. It is generally accepted that, after Hubert’s death in 1426, the younger Jan van Eyck took up his stead and completed the painting, when it was then displayed in St. Bavo’s Cathedral where some 600 years later it still stands today. It is amongst the important pieces of Western art ever created, laying the foundations for the Renaissance and changing the very world it sought to represent.

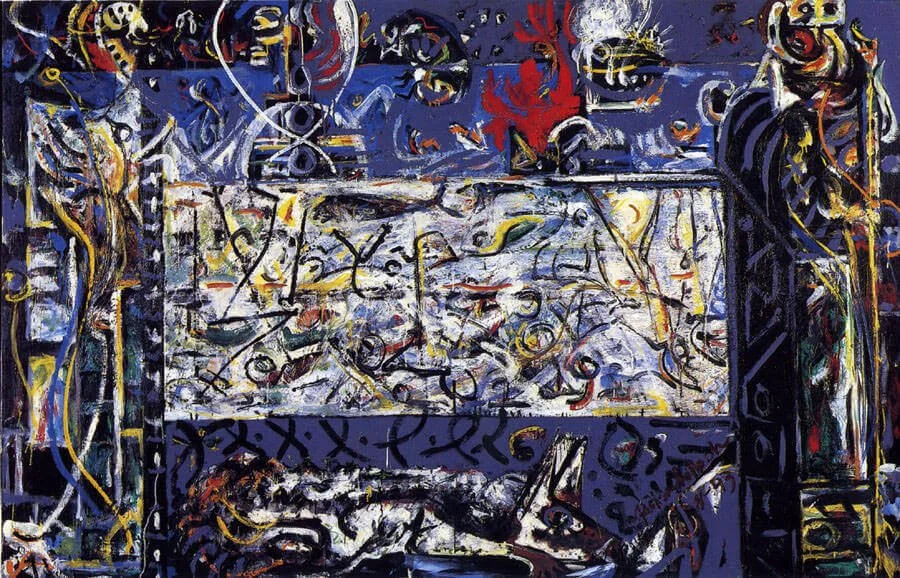

Guardians of the Secret

POLLOCK

A seminal early work by Pollock, Guardians of the Secret was a synthesis of disparate influences into a supremely modern work. Long inspired by the Native American art that he saw as a child growing up in the American West, Pollock visited the Indian Art Exhibition at MOMA with his Jungian analyst in 1941. The totemic forms of Guardians pay homage to Native American art while exploring his own warring psyche. Pollock saw art making as an attempt to heal himself, a shamanistic, religious ritual that gives over to chance, in the same way that Native American sand painting was seen as a healing practice.

JACKSON POLLOCK

JACKSON POLLOCK, 1943

A seminal early work by Pollock, Guardians of the Secret was a synthesis of disparate influences into a supremely modern work. Long inspired by the Native American art that he saw as a child growing up in the American West, Pollock visited the Indian Art Exhibition at MOMA with his Jungian analyst in 1941. The totemic forms of Guardians pay homage to Native American art while exploring his own warring psyche. Pollock saw art making as an attempt to heal himself, a shamanistic, religious ritual that gives over to chance, in the same way that Native American sand painting was seen as a healing practice.

Bliz-aard Ball Sale

HAMMONS

On the corner of Cooper Square, opposite Cooper Union where Hammons taught lessons on material specificity and conceptual reverb, David Hammons laid out a North African rug, arranged various snowballs of different sizes and began selling his wares. Alongside counterfeit designer good, jewellery and army surplus vendors, wearing inconspicuous garb, Hammons was making a statement. The nature of that statement, even after 40 years of academic analysis, remains vague. Hammons, one of the most important contemporary artists, has always existed with intention outside of reach of the art world. The work is almost an idiom, the literal action absurd and ephermeral. It is a work with the sole purpose to evade us, or as Hammons says, ‘don’t you know, chasing these stories is what is is?’.

DAVID HAMMONS

DAVID HAMMONS, 1983

On the corner of Cooper Square, opposite Cooper Union where he taught lessons on material specificity and conceptual reverb, David Hammons laid out a North African rug, arranged various snowballs of different sizes and began selling his wares. Alongside counterfeit designer goods, jewellery and army surplus vendors, wearing inconspicuous garb, Hammons was making a statement. The nature of that statement, even after 40 years of academic analysis, remains vague. Hammons, one of the most important contemporary artists, has always existed with intention outside of reach of the art world. The work is almost an idiom, the literal action absurd and ephermeral. It is a work with the sole purpose to evade us, or as Hammons says, ‘don’t you know, chasing these stories is what is is?’.

Breath of Leaves

PENONE

Guiseppe Penone lay down in a pile of leaves and breathed. He breathed nature and left his imprint. The work is transient and in a state of constant change. The slightest move from the spectator will be enough to move a single leaf and change the construction. Penone made art outside of the system. Alongside a small group of Italian artists, he developed a genre known as Arte Povera, or poor art. Creating work from limited, affordable resources, both natural and man-made, he questioned the means of production and the human relationship with nature. He did not strive for immortality; his work will be carried away by the wind.

GIUSEPPE PENONE

GIUSEPPE PENONE, 1979

Guiseppe Penone lay down in a pile of leaves and breathed. He breathed nature and left his imprint. The work is transient and in a state of constant change. The slightest move from the spectator will be enough to move a single leaf and change the construction. Penone made art outside of the system. Alongside a small group of Italian artists, he developed a genre known as Arte Povera, or poor art. Creating work from limited, affordable resources, both natural and man-made, he questioned the means of production and the human relationship with nature. He did not strive for immortality; his work will be carried away by the wind.

The Rock Needle and the Porte D’Aval

MONET

Monet returned to the beaches of Normandy again and again. Raised nearby, the limestone cliffs and natural arches embedded themselves in his psyche from childhood and Monet would escape the Urban environment to obsessively paint the rock formations. He was relentlessly in his documentation, capturing every viewpoint, at every time of day. He became a hunter of change, studying the way the moving light altered the colours and shadows. He would paint up to five of six canvases a day, abandoning them as the changing sky dictated. Monet’s whole life can be told in his paintings of Porte D’Aval – the appearance of the rocks changes not just with time but with the man, with his mood and experiences. As with all obsessions, Monet projected himself onto these arches, beach and sea, drawing them as if out of necessity.

CLAUDE MONET

CLAUDE MONET, 1886

Monet returned to the beaches of Normandy again and again. Raised nearby, the limestone cliffs and natural arches embedded themselves in his psyche from childhood and Monet would escape the Urban environment to obsessively paint the rock formations. He was relentlessly in his documentation, capturing every viewpoint, at every time of day. He became a hunter of change, studying the way the moving light altered the colours and shadows. He would paint up to five of six canvases a day, abandoning them as the changing sky dictated. Monet’s whole life can be told in his paintings of Porte D’Aval – the appearance of the rocks changes not just with time but with the man, with his mood and experiences. As with all obsessions, Monet projected himself onto these arches, beach and sea, drawing them as if out of necessity.

Isabella and the Pot of Basil

HUNT

Itself derived from Boccaccio’s Lisabetta, John Keats’ Isabella mirrors the Decameron original - the tale of its titular protagonist, centred around the murder of her lover at her brothers’ hands. Though his body is hidden, his spirit remains long enough to inform her of the tragedy; leading Isabella to exhume the body before burying its head in a pot of basil, which she spends the rest of her days caring for obsessively, convinced that Lorenzo’s voice still carries from the soil. The poem served as inspiration for many of the great Pre-Raphaelite painters; particularly William Holman Hunt, who immortalised his wife Fanny’s features as Isabella after she died during the painting’s creation.

WILLIAM HOLMAN HUNT

WILLIAM HOLMAN HUNT, 1868

Itself derived from Boccaccio’s Lisabetta, John Keats’ Isabella mirrors the Decameron original - the tale of its titular protagonist, centred around the murder of her lover at her brothers’ hands. Though his body is hidden, his spirit remains long enough to inform her of the tragedy; leading Isabella to exhume the body before burying its head in a pot of basil, which she spends the rest of her days caring for obsessively, convinced that Lorenzo’s voice still carries from the soil. The poem served as inspiration for many of the great Pre-Raphaelite painters; particularly William Holman Hunt, who immortalised his wife Fanny’s features as Isabella after she died during the painting’s creation.

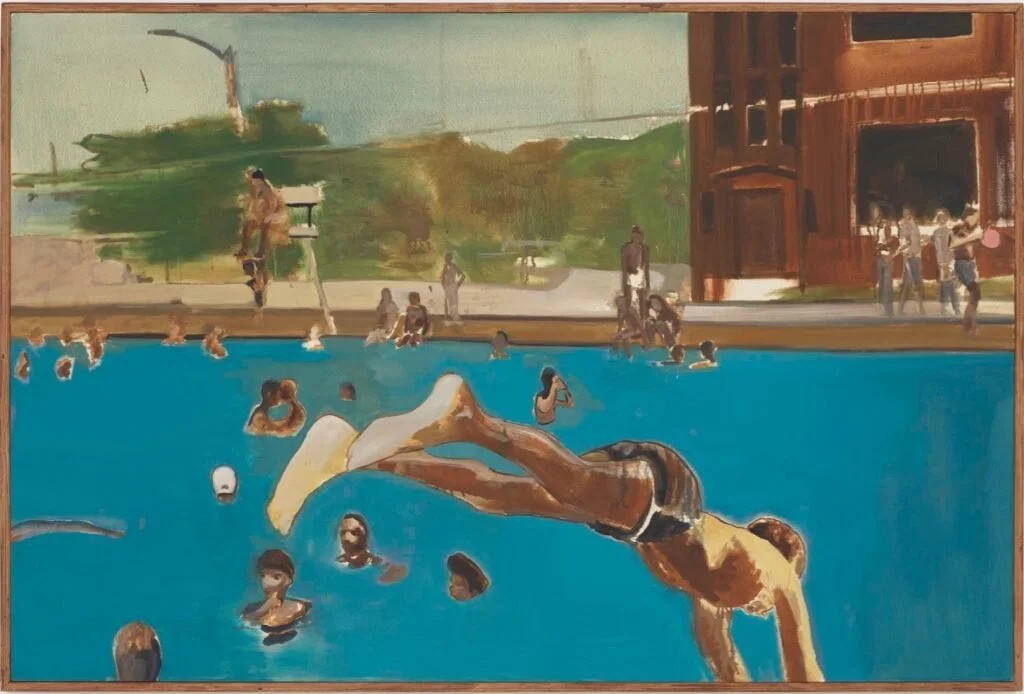

1975

DAVIS

The earthen pool is lined with umber bodies. Frozen headlong, a boy is captured middive into a turquoise pool, his fellow swimmers similarly caught in stillness. The scene is fuzzily painted - an artificially shallow depth of field, this moment focused upon the diving figure while blurring the other poolgoers. Davis’ control over his palette is reminiscent of the functioning of memory — capturing and recording certain details or foci, but never quite managing to condense into the moment it originally was. The result is a decidedly analogue effect, a faded postcard from a resort long passed by. Davis drew from quotidian scenes like these often, but it is their very mundanity that in turn infuses them with both livelihood and meaning. He painted everyday magic, permutating his subjects from the mediocre into a sun-slick fantasy.

NOAH DAVIS

NOAH DAVIS, 2013

The earthen pool is lined with umber bodies. Frozen headlong, a boy is captured middive into a turquoise pool, his fellow swimmers similarly caught in stillness. The scene is fuzzily painted - an artificially shallow depth of field, this moment focused upon the diving figure while blurring the other poolgoers. Davis’ control over his palette is reminiscent of the functioning of memory — capturing and recording certain details or foci, but never quite managing to condense into the moment it originally was. The result is a decidedly analogue effect, a faded postcard from a resort long passed by. Davis drew from quotidian scenes like these often, but it is their very mundanity that in turn infuses them with both livelihood and meaning. He painted everyday magic, permutating his subjects from the mediocre into a sun-slick fantasy.

The Resurrection

TITIAN

Titian’s The Resurrection had many inspirations, ranging from ancient sculptures to religious frescoes but most direct of all was his own painting Polyptych of the Resurrection, painted some 20 years earlier. It is, however, bolder, brighter, more affecting than its inspirations, it is glorious in its depiction of Christ rising from his tomb. The power we feel looking at the work is matched by the figure's awe in the lower half. The undisputed master of the Venetian Renaissance, Titian was stylistically restless throughout his life, maturing and changing, updating and revisiting his oeuvre. The confidence of his youth gave way to a self-critical maturity — he became an obsessive perfectionist, working on single paintings for up to 10 years and re-imagining the early work which gave him his fame and fortune. The Resurrection, originally part of a diptych for a processional Banner for the Corpus Domini brotherhood in Urbino, is a shining example of this revisionism. Titian made his past the muse for his present, and achieved perfection in the process.

Titian

TITIAN, c.1544. OIL ON CANVAS.

Titian’s The Resurrection had many inspirations, ranging from ancient sculptures to religious frescoes but most direct of all was his own painting Polyptych of the Resurrection, painted some 20 years earlier. It is, however, bolder, brighter, more affecting than its inspirations, it is glorious in its depiction of Christ rising from his tomb. The power we feel looking at the work is matched by the figure's awe in the lower half. The undisputed master of the Venetian Renaissance, Titian was stylistically restless throughout his life, maturing and changing, updating and revisiting his oeuvre. The confidence of his youth gave way to a self-critical maturity — he became an obsessive perfectionist, working on single paintings for up to 10 years and re-imagining the early work which gave him his fame and fortune. The Resurrection, originally part of a diptych for a processional Banner for the Corpus Domini brotherhood in Urbino, is a shining example of this revisionism. Titian made his past the muse for his present, and achieved perfection in the process.

Breakdown

LANDY

On the morning of February 10th, 2001, Michael Landy owned 7,227 objects. 14 days later he owned nothing but the clothes on his back and 5.75 tons of powdered consumer and personal goods. In a disused storefront, Landy and a team of technicians, mechanics, assistants and artists loaded up everything Landy owned - artwork, clothes, family heirlooms, a Saab 900 Turbo, newspaper clippings, expired spices, defunct AV equipment, range ovens, living rooms chairs - onto a specially constructed conveyor belt and began breaking them down. Each object was disassembled and then pulped and powdered until nothing remained. It is an artwork with no tangible end product.

MICHAEL LANDY

MICHAEL LANDY, 2001

On the morning of February 10th, 2001, Michael Landy owned 7,227 objects. 14 days later he owned nothing but the clothes on his back and 5.75 tons of powdered consumer and personal goods. In a disused storefront, Landy and a team of technicians, mechanics, assistants and artists loaded up everything Landy owned - artwork, clothes, family heirlooms, a Saab 900 Turbo, newspaper clippings, expired spices, defunct AV equipment, range ovens, living rooms chairs - onto a specially constructed conveyor belt and began breaking them down. Each object was disassembled and then pulped and powdered until nothing remained. It is an artwork with no tangible end product.

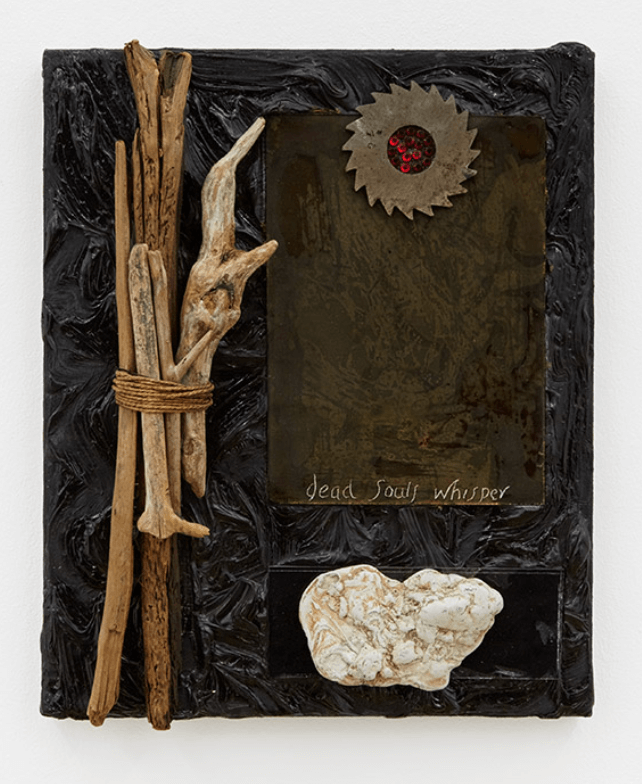

Black Painting

JARMAN

Derek Jarman trawled the shingles of Dungeness Beach, in the shadow of the Nuclear Power Plant, picking up lost objects. He did the same in flea markets in London. Jetsam and detritus became his inspiration for his series of Black Paintings. Using the same tar his cottage was coated in as the base, he created these assemblages as he began to die from HIV. They can be read as Memento Mori, indeed some can even be seen as abstract headstones, but they are not about the inevitability of just Jarman’s death. They are about the collective, the past owners of these lost objects, and the uniting of them together in something literally dead - tar. So they are about the inevitability of dying but too the will to live. Jarman saved objects and gave them life, he joined together the rejected to create a unified new.

DEREK JARMAN

DEREK JARMAN, 1982 -1991

Derek Jarman trawled the shingles of Dungeness Beach, in the shadow of the Nuclear Power Plant, picking up lost objects. He did the same in flea markets in London. Jetsam and detritus became his inspiration for his series of Black Paintings. Using the same tar his cottage was coated in as the base, he created these assemblages as he began to die from HIV. They can be read as Memento Mori, indeed some can even be seen as abstract headstones, but they are not about the inevitability of just Jarman’s death. They are about the collective, the past owners of these lost objects, and the uniting of them together in something literally dead - tar. So they are about the inevitability of dying but too the will to live. Jarman saved objects and gave them life, he joined together the rejected to create a unified new.

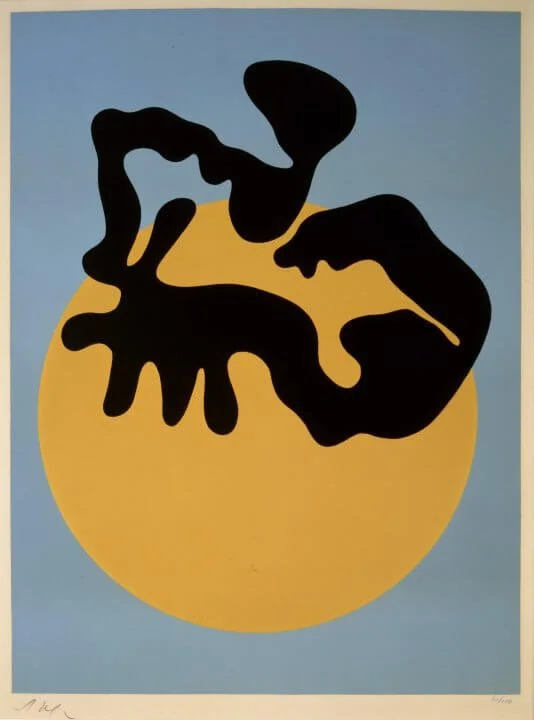

Non Loin du Solei, De La Lune et Des ‘Etoiles’

ARP

Arp saw chance as his greatest collaborator. Throughout his career, working across almost every medium available to him, Arp bridged the gap between 20th century art movements, but his breadth belies a consistency of thinking. Arp worked with form first, generating shapes and letting the artwork move from there. The conscious mind was a hindrance in creation – natural forms dominate his work and he presents visual information as an alien seeing it for the first time. The father of Organic Abstraction, his titles were the last element of any work to be considered. Here, a yellow circle is the sun, the moon, and the stars, and we are close to them all.

JEAN ARP

JEAN ARP, 1962–1963

Arp saw chance as his greatest collaborator. Throughout his career, working across almost every medium available to him, Arp bridged the gap between 20th century art movements, but his breadth belies a consistency of thinking. Arp worked with form first, generating shapes and letting the artwork move from there. The conscious mind was a hindrance in creation – natural forms dominate his work and he presents visual information as an alien seeing it for the first time. The father of Organic Abstraction, his titles were the last element of any work to be considered. Here, a yellow circle is the sun, the moon, and the stars, and we are close to them all.

The Swan

KLINT

For Hilma af Klint, whose forays into abstract art were perhaps the first to occur in the Western world, swans were stepping stones - symbols of the otherworldly wisdom that higher beings Georg and Ananda allegedly imparted upon the painter during a spiritual seance in 1904. The majestic swan symbolised the ‘grandeur of the spirit’ in Theosophy, a spiritualist movement of great interest to Klint; in alchemy, the swan represents the union of opposites necessary for the creation of the philosopher’s stone, or the power to transform base metals into gold. In the Swan series, af Klint blends established symbolism with her own idiosyncrasies, progressing from figurative swans to geometric forms suggestive of the higher dimensions she sought.

HILMA AF KLINT

HILMA AF KLINT, 1915

For Hilma af Klint, whose forays into abstract art were perhaps the first to occur in the Western world, swans were stepping stones - symbols of the otherworldly wisdom that higher beings Georg and Ananda allegedly imparted upon the painter during a spiritual seance in 1904. The majestic swan symbolised the ‘grandeur of the spirit’ in Theosophy, a spiritualist movement of great interest to Klint; in alchemy, the swan represents the union of opposites necessary for the creation of the philosopher’s stone, or the power to transform base metals into gold. In the Swan series, af Klint blends established symbolism with her own idiosyncrasies, progressing from figurative swans to geometric forms suggestive of the higher dimensions she sought.

Flaming June

LEIGHTON

Flaming June is a work of painterly deception. The work is so striking, so classically beautiful, conforming to aesthetic ideals and sacred geometry of the golden ratio that it’s real tricks are hidden from us. Leighton was a classicist, a holdover from a generation before him and even while revered in his time, he was out of fashion before he reached old age. Yet hiding in this classical work is something profoundly modern because this is not a portrait of a sleeping woman so much as an investigation of form and colour. The model is contorted in an impossible shape, she becomes a circle. The elongated thigh, brings her body sweepy into geometry, housed in a perfectly squared canvas. This work exists across planes. You are drawn in by an exquisite, delicate rendering of a lazy spring day, and it is only your subconscious that sees the natural, minimal forms of the work.

SIR FREDERIC LEIGHTON

SIR FREDERIC LEIGHTON, 1895

Flaming June is a work of painterly deception. The work is so striking, so classically beautiful, conforming to aesthetic ideals and sacred geometry of the golden ratio that it’s real tricks are hidden from us. Leighton was a classicist, a holdover from a generation before him and even while revered in his time, he was out of fashion before he reached old age. Yet hiding in this classical work is something profoundly modern because this is not a portrait of a sleeping woman so much as an investigation of form and colour. The model is contorted in an impossible shape, she becomes a circle. The elongated thigh, brings her body sweepy into geometry, housed in a perfectly squared canvas. This work exists across planes. You are drawn in by an exquisite, delicate rendering of a lazy spring day, and it is only your subconscious that sees the natural, minimal forms of the work.

A Line Made by Walking

LONG

Richard Long, on his commute from his home to his art school, stopped off in a grassy field and walked back and forth in a straight path until a line was visible. He photographed the result. It may be the first example of a sculpture made by feet, not hands. Yet sculpture may not be the right way to describe it. Is the action of making the line the artwork? Or the line itself? Or the documentation of it? Shockingly simple, Long’s Line is a conceptual, minimalist work posing questions with no requirement for answers. It is a landmark of land art, and you can make it in your own back garden.

RICHARD LONG

RICHARD LONG, 1967

Richard Long, on his commute from his home to his art school, stopped off in a grassy field and walked back and forth in a straight path until a line was visible. He photographed the result. It may be the first example of a sculpture made by feet, not hands. Yet sculpture may not be the right way to describe it. Is the action of making the line the artwork? Or the line itself? Or the documentation of it? Shockingly simple, Long’s Line is a conceptual, minimalist work posing questions with no requirement for answers. It is a landmark of land art, and you can make it in your own back garden.

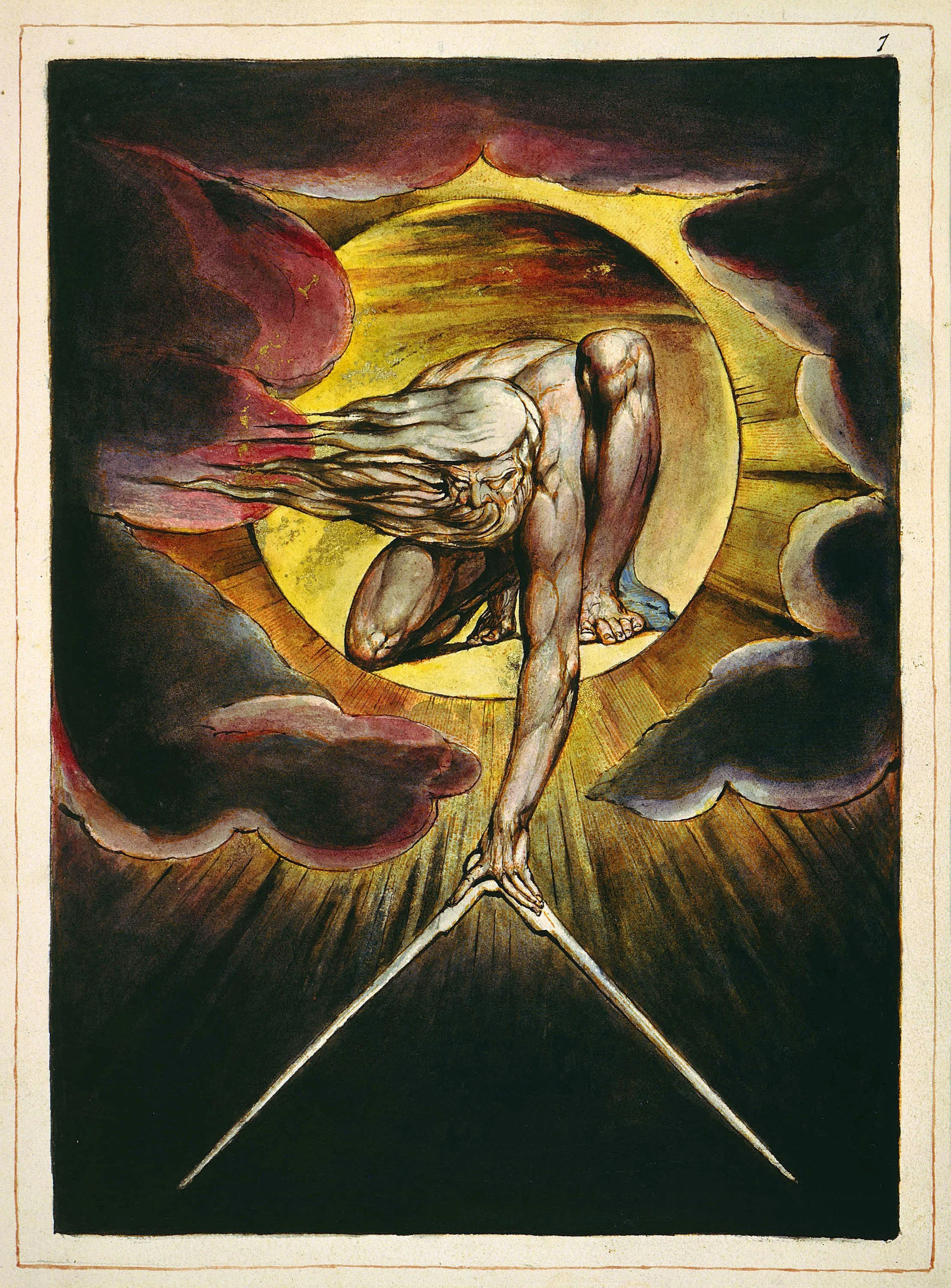

The Ancient of Days

BLAKE

William Blake was tormented by visions. From his early childhood he saw, as clear as day, God’s face pressed against his window, angels playing amongst haystacks, the prophet Ezekiel standing in his room. For him, imagination, reality, God and human existence itself were all one. The Ancient of Days begins his book Europe, one of Blake’s ‘Prophetic Works’. It is not a vision of the future, but of the present, as seen by the honest and the wise. The figure depicted is Urizen, holding a compass over the dark void below him. Urizen was the embodiment of Law and Reason, and here he casts, with violence and mathematics, order onto the world below him. Blake saw this image in his reality, and made the print patiently awaiting the rest of the world to see it too.

WILLIAM BLAKE

WILLIAM BLAKE, 1794

William Blake was tormented by visions. From his early childhood he saw, as clear as day, God’s face pressed against his window, angels playing amongst haystacks, the prophet Ezekiel standing in his room. For him, imagination, reality, God and human existence itself were all one. The Ancient of Days begins his book Europe, one of Blake’s ‘Prophetic Works’. It is not a vision of the future, but of the present, as seen by the honest and the wise. The figure depicted is Urizen, holding a compass over the dark void below him. Urizen was the embodiment of Law and Reason, and here he casts, with violence and mathematics, order onto the world below him. Blake saw this image in his reality, and made the print patiently awaiting the rest of the world to see it too.