Summer (Dune in Zeeland)

MONDRIAN

Mondrian’s abstract, geometric squares came to define a new way of thinking in the 20th Century, but in 1910 he was experiencing a transitional period. Coming from formal training - his early work was impressionistic depictions of pastoral scenes - he retreated to the Holland Coast and began painting the Dunes of the Zeeland River. Here, over the course of two years, his work became increasingly abstract. Summer marks a turning point. Though still painting from life, the scene is freed from reality. It becomes a study of form and colour, with sweeping blue shapes polluted by bright yellow shadows. The natural world becomes an inspiration, not a muse.

PIET MONDRIAN

PIET MONDRIAN, 1910

Mondrian’s abstract, geometric squares came to define a new way of thinking in the 20th Century, but in 1910 he was experiencing a transitional period. Coming from formal training - his early work was impressionistic depictions of pastoral scenes - he retreated to the Holland Coast and began painting the Dunes of the Zeeland River. Here, over the course of two years, his work became increasingly abstract. Summer marks a turning point. Though still painting from life, the scene is freed from reality. It becomes a study of form and colour, with sweeping blue shapes polluted by bright yellow shadows. The natural world becomes an inspiration, not a muse.

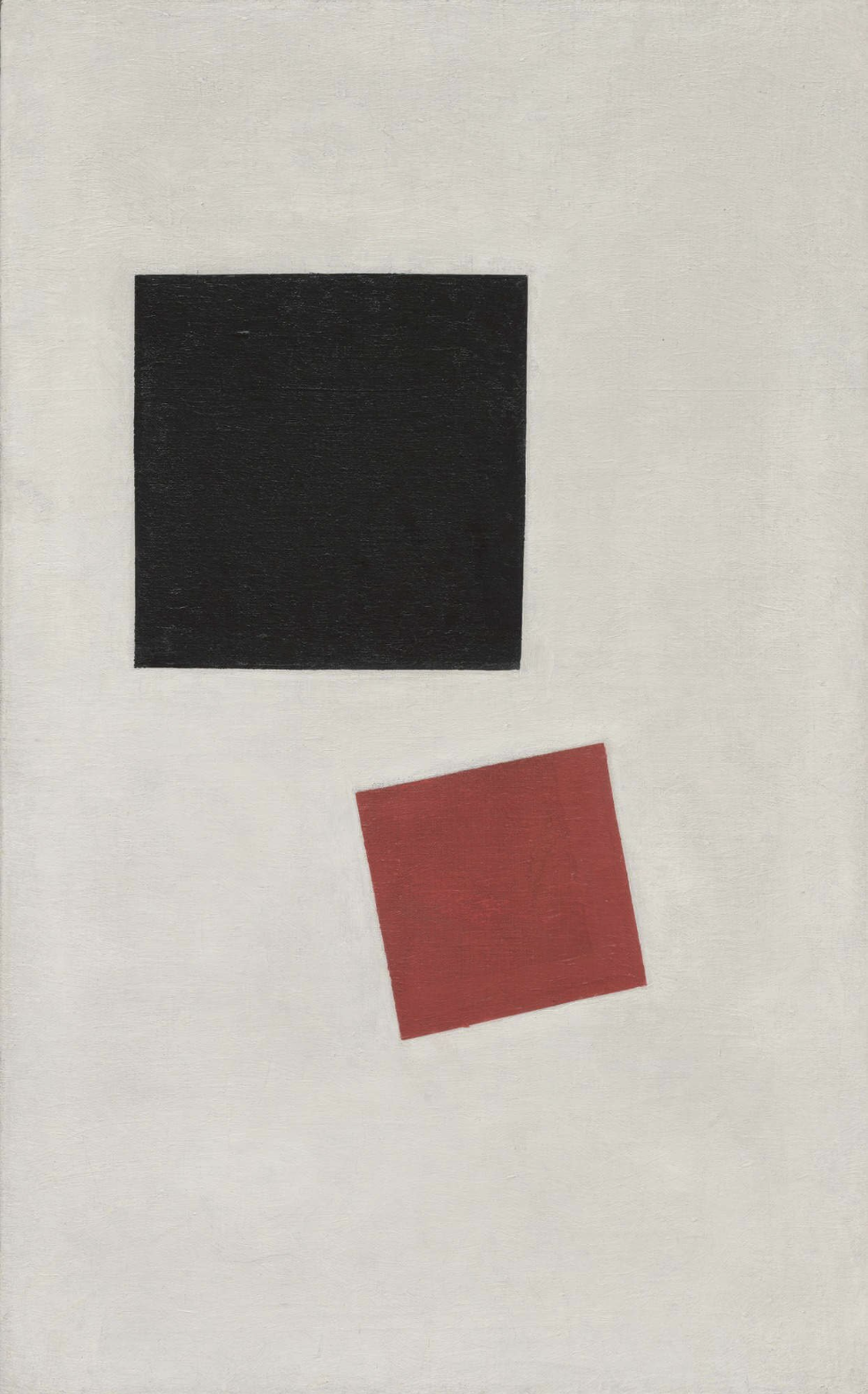

Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack – Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension

MALEVICH

A world in turmoil and Malevich answers with two squares. Decades before Mondrian reduced modern art to geometry, the Russian Suprematists were liberating art from reality. The Suprematists above all were interested in feeling. The war was raging, Russia was in a period of immense change, and daily reality seemed an unappealing and tenuous construct. So they looked to emotion, unchained from anything else. Despite the tongue-in-cheek title, Malevich’s Black and Red Square is art in its barest form. There are no distractions, no memories, no allusions, there is only form and shape, and emotion. Not prescribed emotion, but engendered feeling. Malevich gives you almost nothing, and when you have nothing, the only option is to feel something.

KAZIMIR MALEVICH

KAZIMIR MALEVICH, 1915

A world in turmoil and Malevich answers with two squares. Decades before Mondrian reduced modern art to geometry, the Russian Suprematists were liberating art from reality. The Suprematists above all were interested in feeling. The war was raging, Russia was in a period of immense change, and daily reality seemed an unappealing and tenuous construct. So they looked to emotion, unchained from anything else. Despite the tongue-in-cheek title, Malevich’s Black and Red Square is art in its barest form. There are no distractions, no memories, no allusions, there is only form and shape, and emotion. Not prescribed emotion, but engendered feeling. Malevich gives you almost nothing, and when you have nothing, the only option is to feel something.

Cool Summer

FRANKENTHALER

Helen Frankenthaler works in collaboration with her materials. Part of the second wave of Post-War American Abstract painters, Frankenthaler split from her contemporaries and almost single handedly ushered in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Color-Field painting. She created a technique called ‘soak-staining’, thinning down oil paint to the consistency of watercolour and letting the textures of the raw canvas dictate the movement of the paint. In doing so, she expanded the possibilities of abstraction. Her figurative and personal concepts became inherently and intentionally abstracted by her process. Frankenthaler was in a dialogue with her artworks — as an equal partner to her materials she understood that painting was not about control but about expression and contradiction. ‘What a lie,’ she said about her process, ‘what trickery — how beautiful is the very idea of painting.’

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN FRANKENTHALER, 1962. OIL ON CANVAS.

Helen Frankenthaler works in collaboration with her materials. Part of the second wave of Post-War American Abstract painters, Frankenthaler split from her contemporaries and almost single handedly ushered in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Color-Field painting. She created a technique called ‘soak-staining’, thinning down oil paint to the consistency of watercolour and letting the textures of the raw canvas dictate the movement of the paint. In doing so, she expanded the possibilities of abstraction. Her figurative and personal concepts became inherently and intentionally abstracted by her process. Frankenthaler was in a dialogue with her artworks — as an equal partner to her materials she understood that painting was not about control but about expression and contradiction. ‘What a lie,’ she said about her process, ‘what trickery — how beautiful is the very idea of painting.’

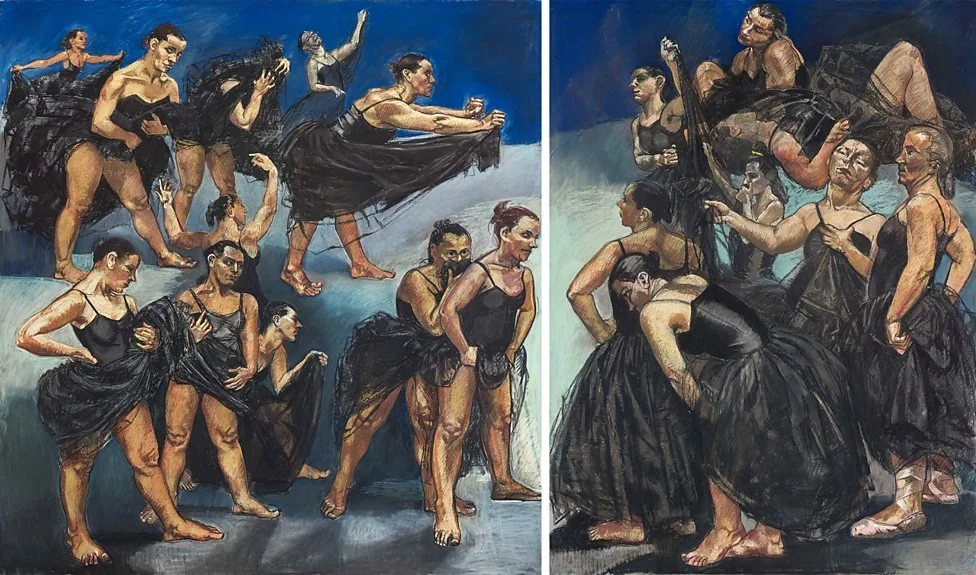

Ostrich Dancers

REGO

Rego’s women are frustrated. In stark contrast to painterly depictions of ballerinas from the past, Rego’s dancers are inelegant and uncomfortable;frustrated with themselves, with their garb and with each other. Taking its name and inspiration from Disney’s Fantasia, The Dancing Ostriches share few similarities with their graceful namesakes but they both exist in a storybook type world. ‘If you don’t know what to draw, read a story’, Rego says, and for her this is often fairy tales in their traditional guise – dark and beautiful. Rego’s ballerinas are her friends, her muses and sometimes herself. They are figures in dialogue with themselves.

PAULA REGO

PAULA REGO, 1995

Rego’s women are frustrated. In stark contrast to painterly depictions of ballerinas from the past, Rego’s dancers are inelegant and uncomfortable; frustrated with themselves, with their garb and with each other. Taking its name and inspiration from Disney’s Fantasia, The Dancing Ostriches share few similarities with their graceful namesakes but they both exist in a storybook type world. ‘If you don’t know what to draw, read a story’, Rego says, and for her this is often fairy tales in their traditional guise – dark and beautiful. Rego’s ballerinas are her friends, her muses and sometimes herself. They are figures in dialogue with themselves.

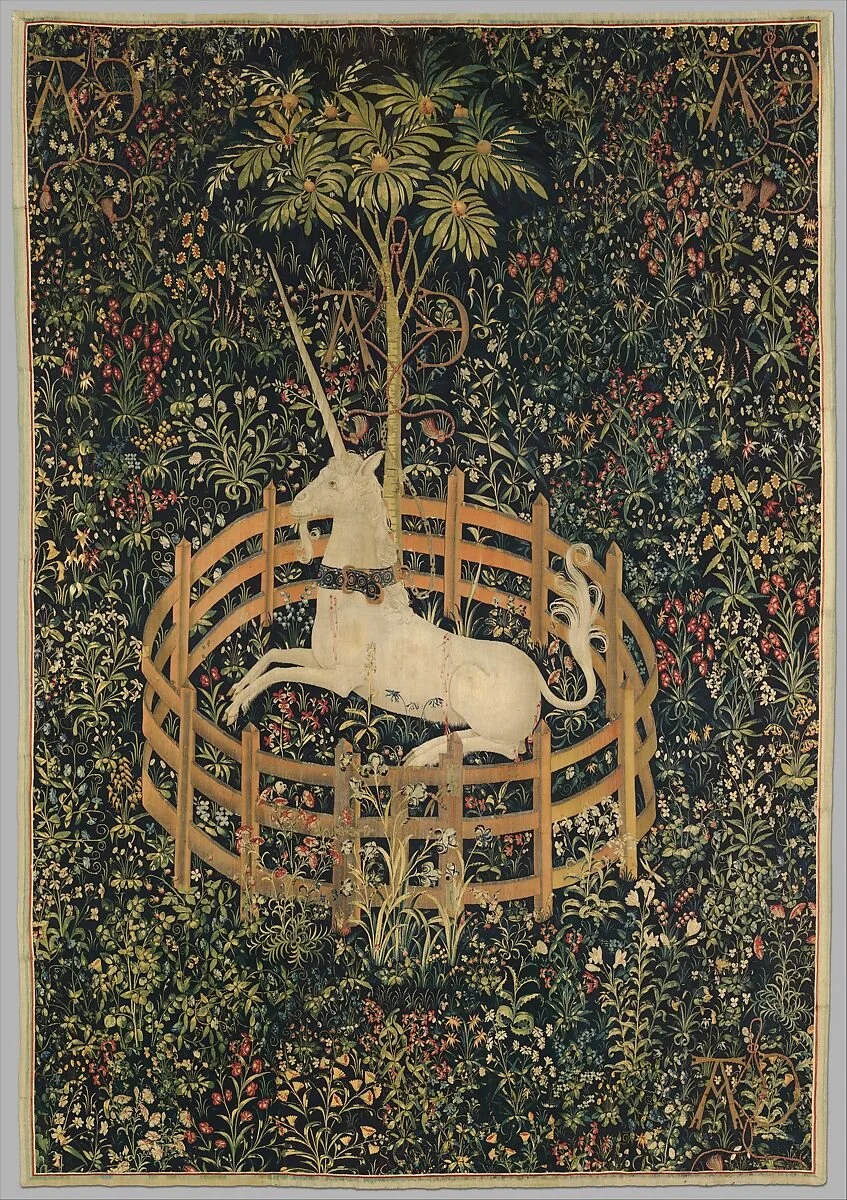

Unicorn Tapestries

ARTIST UNKNOWN

The greatest inheritance of the Middle Ages, The Unicorn Tapestries are shrouded in mystery. Their meaning and origin have been long unknown but numerous theories persist. The Unicorn has dual symbolism, representing both Christ and Virginity, and the story told in the seven works can be read as either. The Unicorn Rests in the Garden, however, is a stand-alone work. Caged and bound, surrounded by a bountiful garden and below a pomegranate tree, the Unicorn seems content. The fence is low enough to jump and the chain unsecured. The Unicorn, perhaps, is content in his confinement.

ARTIST UNKNOWN

UNKNOWN ARTIST, 1495–1505

The greatest inheritance of the Middle Ages, The Unicorn Tapestries are shrouded in mystery. Their meaning and origin have been long unknown but numerous theories persist. The Unicorn has dual symbolism, representing both Christ and Virginity, and the story told in the seven works can be read as either. The Unicorn Rests in the Garden, however, is a stand-alone work. Caged and bound, surrounded by a bountiful garden and below a pomegranate tree, the Unicorn seems content. The fence is low enough to jump and the chain unsecured. The Unicorn, perhaps, is content in his confinement.

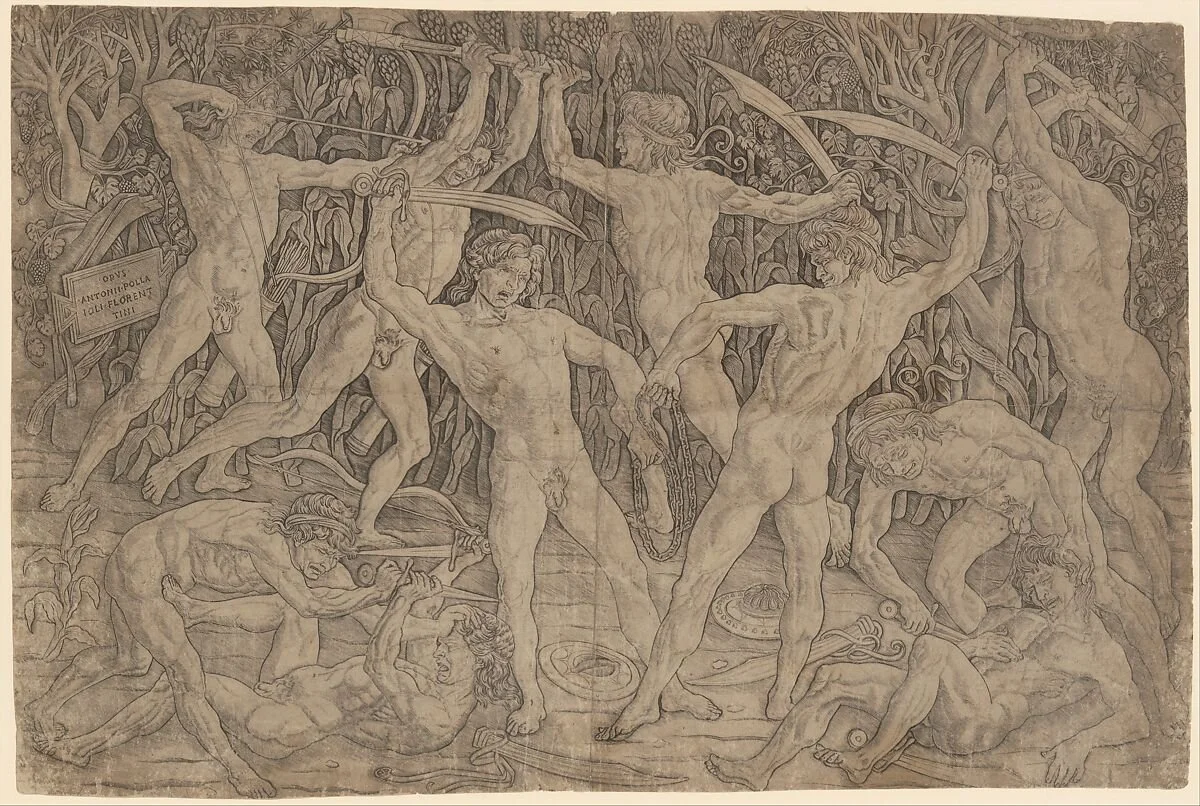

Battle of the Nudes

POLLAIUOLO

Made in the 15th Century, this work has far more questions than answers. Ten nude men, with bodies contorted in various states and shapes, fight against an impossibly fantastical background. There are no context clues here, we do not know the era nor why they are battling, the location is vague and each man seems to be fighting a mirror image of himself. Yet this small print is among the most influential works of the Renaissance for its violent depiction of the male body. The work has often been interpreted as a master document of sorts, a guide for other artists of how to draw the body in motion. The two figures standing at the front are reflections of each other, one from the front and one from behind. In harmonious aggression, these figures became a blueprint for generations of artists.

ANTONIO DEL POLLAIUOLO

ANTONIO DEL POLLAIUOLO, 1465–1475

Made in the 15th Century, this work has far more questions than answers. Ten nude men, with bodies contorted in various states and shapes, fight against an impossibly fantastical background. There are no context clues here, we do not know the era nor why they are battling, the location is vague and each man seems to be fighting a mirror image of himself. Yet this small print is among the most influential works of the Renaissance for its violent depiction of the male body. The work has often been interpreted as a master document of sorts, a guide for other artists of how to draw the body in motion. The two figures standing at the front are reflections of each other, one from the front and one from behind. In harmonious aggression, these figures became a blueprint for generations of artists.

White Painting

RAUSCHENBERG

How can an artwork be created untouched by human hands? This was the question Rauschenberg was contemplating when he created the White Paintings. Stark canvases painted completely white with no visible brush strokes, in a series of different panel numbers. For Rauschenberg, these were not one-off artworks, but instead remakeable works. They were a concept, a thought experiment that anyone could, and he hoped would, be able to reproduce. John Cage, for whom these paintings inspired his silent composition 4’33, said the paintings were ‘airports for lights, shadows, and particles’. That the artwork was the world around them, they were merely a vessel for amplification. Rauschenberg succeeded – even if the plane was made by human hands, it became simply the background for the artwork of the world that is happening around us constantly.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG, 1951

How can an artwork be created untouched by human hands? This was the question Rauschenberg was contemplating when he created the White Paintings. Stark canvases painted completely white with no visible brush strokes, in a series of different panel numbers. For Rauschenberg, these were not one-off artworks, but instead remakeable works. They were a concept, a thought experiment that anyone could, and he hoped would, be able to reproduce. John Cage, for whom these paintings inspired his silent composition 4’33, said the paintings were ‘airports for lights, shadows, and particles’. That the artwork was the world around them, they were merely a vessel for amplification. Rauschenberg succeeded – even if the plane was made by human hands, it became simply the background for the artwork of the world that is happening around us constantly.

Model in a Swimsuit

MAAR

Light and shade ripple along the bather. Clad in a two-piece swimsuit, she is quintessentially daring for 1936. Her arms raised in statuesque positioning, the figure appears to float unencumbered - the longer you look, the more it may seem like this mystery woman is drifting through a dream. But neither woman nor pool were ever actually acquainted - instead, this is one of the first true Surrealist photographs. Influenced by her romantic relationship with Pablo Picasso, Maar integrated Surrealism into her fashion photography - as Picasso said, “Inside every photographer is a painter trying to get out.” Here, Maar was ‘painting’ in the darkroom, superimposing two different negatives of model and pool to create the final surreal image. The work is an anomaly in Surrealism; its trick so well executed that it might be lost to a casual glance.

DORA MAAR

DORA MAAR, 1936

Light and shade ripple along the bather. Clad in a two-piece swimsuit, she is quintessentially daring for 1936. Her arms raised in statuesque positioning, the figure appears to float unencumbered - the longer you look, the more it may seem like this mystery woman is drifting through a dream. But neither woman nor pool were ever actually acquainted - instead, this is one of the first true Surrealist photographs. Influenced by her romantic relationship with Pablo Picasso, Maar integrated Surrealism into her fashion photography - as Picasso said, “Inside every photographer is a painter trying to get out.” Here, Maar was ‘painting’ in the darkroom, superimposing two different negatives of model and pool to create the final surreal image. The work is an anomaly in Surrealism; its trick so well executed that it might be lost to a casual glance.

New York 1979

KWONG CHI

In the suit of a Chinese dignitary, Tseng Kwong Chi travelled the world taking self-portraits against icons of Western, and later Eastern, civilisation. Part of a group of radical artists working out of New York in the late 70s and 80s, Tseng was born to parents exiled from Hong Kong but considered himself a citizen of the world. In his portraiture he is emotionless, wearing dark glasses and his ‘Mao Suit’, quick release cable in hand – an ambiguous ambassador. The images are funny, yet in their humour and in their repetition, there is an unplaceable profundity. Kwong Chi was playful and ambiguous about his work – a gay, radical young man in the suit of authoritarianism standing in front of the symbols of liberation and capitalism. They are not critiquing, nor celebrating, they are simply a way of placing himself within, and separate from, the many worlds he felt he belonged to.

TSENG KWONG CHI

TSENG KWONG CHI, 1979

In the suit of a Chinese dignitary, Tseng Kwong Chi travelled the world taking self-portraits against icons of Western, and later Eastern, civilisation. Part of a group of radical artists working out of New York in the late 70s and 80s, Tseng was born to parents exiled from Hong Kong but considered himself a citizen of the world. In his portraiture he is emotionless, wearing dark glasses and his ‘Mao Suit’, quick release cable in hand – an ambiguous ambassador. The images are funny, yet in their humour and in their repetition, there is an unplaceable profundity. Kwong Chi was playful and ambiguous about his work – a gay, radical young man in the suit of authoritarianism standing in front of the symbols of liberation and capitalism. They are not critiquing, nor celebrating, they are simply a way of placing himself within, and separate from, the many worlds he felt he belonged to.

Onement VI

NEWMAN

‘There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance,’ Barnett Newman’s show notes begin. ‘The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance.’ Known for their large, vibrant fields of colour, parted by a single vertical ‘zip’ running down the centre; Newman’s ‘Onement’ series takes its name from archaic English, meaning ‘at one’. Only close range examination will allow viewers to truly appreciate its building, enveloping washes of ultramarine blue, and in turn the hand that produced them - measuring 8.5 by 10 feet, the extravagant size of Newman’s canvases was intended to provoke this curiosity.

Barnett Newman

BARNETT NEWMAN, 1953. OIL ON CANVAS.

‘There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance,’ Barnett Newman’s show notes begin. ‘The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance.’ Known for their large, vibrant fields of colour, parted by a single vertical ‘zip’ running down the centre; Newman’s ‘Onement’ series takes its name from archaic English, meaning ‘at one’. Only close range examination will allow viewers to truly appreciate its building, enveloping washes of ultramarine blue, and in turn the hand that produced them - measuring 8.5 by 10 feet, the extravagant size of Newman’s canvases was intended to provoke this curiosity.

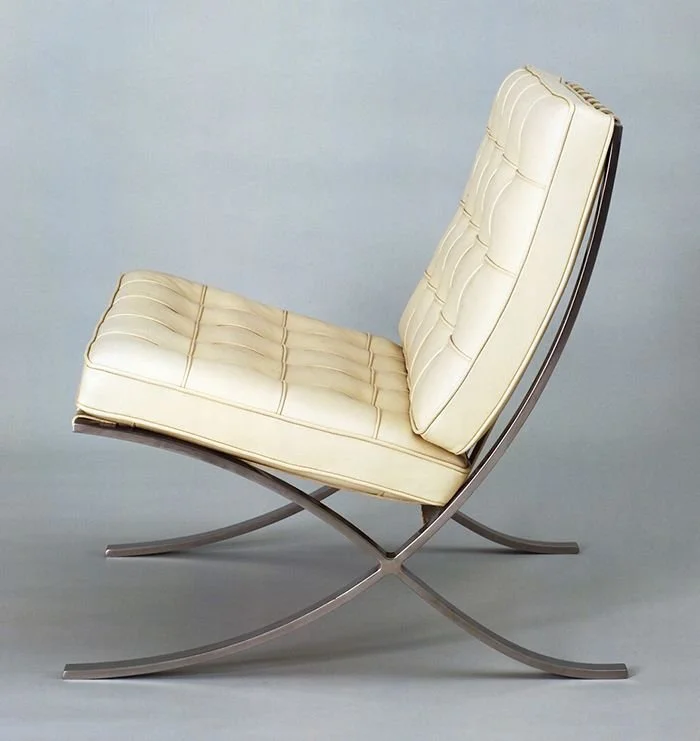

Barcelona Chair

VAN DER ROHE AND REICH

Few objects represent as much. The Barcelona Chair, so named for the Barcelona Exposition where it was designed as a seat for the Spanish King, is a culmination of Bauhaus thought, of Mies van der Rohe’s maxim of ‘Less is More’. It is testament to artisan as artistry, to the collapsing of art practice under a single title of craftsmanship, yet its luxury is an exception to Bauhaus’ commitment to accessibility. It is a literal throne of modernism, taking inspiration from folding chairs of the ancient Romans and 19th Century Neoclassical seating – 2000 years of design were required to create such a work of staggering simplicity. When perhaps no object has had as many permutations, The Barcelona Chair is as close to a Platonic Ideal as exists.

MIES VAN DER ROHE AND LILLY REICH

MIES VAN DER ROHE AND LILLY REICH, 1929

Few objects represent as much. The Barcelona Chair, so named for the Barcelona Exposition where it was designed as a seat for the Spanish King, is a culmination of Bauhaus thought, of Mies van der Rohe’s maxim of ‘Less is More’. It is testament to artisan as artistry, to the collapsing of art practice under a single title of craftsmanship, yet its luxury is an exception to Bauhaus’ commitment to accessibility. It is a literal throne of modernism, taking inspiration from folding chairs of the ancient Romans and 19th Century Neoclassical seating – 2000 years of design were required to create such a work of staggering simplicity. When perhaps no object has had as many permutations, The Barcelona Chair is as close to a Platonic Ideal as exists.

Triplets in Their Bedroom, N.J.

ARBUS

Diane Arbus’ body of work represents a census of post-war America. Roaming the streets of Manhattan armed with her camera and a keen eye for the outsiders and the idiosyncratic, she captured the unseen, the strange, and the mundane. Arbus’ world existed just below the surface of polite 20th century society but her lens was not judgmental. Instead, her images are mysterious, hiding just as much as they reveal. While she photographed people across society — those with disabilities, strippers, carnival workers and nudists — it is her images of twins and triplets that have endured the most. In their flat planes, the subjects look directly at the camera in soft confrontation. Kubrick’s twins in The Shining are undoubtedly inspired by Arbus’ images — both are characters of intrigue and unease, anomalous beauty that captivates. “A photograph”, Arbus said, “is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.”

Diane Arbus

DIANE ARBUS, 1963. SILVER GELATIN PRINT.

Diane Arbus’ body of work represents a census of post-war America. Roaming the streets of Manhattan armed with her camera and a keen eye for the outsiders and the idiosyncratic, she captured the unseen, the strange, and the mundane. Arbus’ world existed just below the surface of polite 20th century society but her lens was not judgmental. Instead, her images are mysterious, hiding just as much as they reveal. While she photographed people across society — those with disabilities, strippers, carnival workers and nudists — it is her images of twins and triplets that have endured the most. In their flat planes, the subjects look directly at the camera in soft confrontation. Kubrick’s twins in The Shining are undoubtedly inspired by Arbus’ images — both are characters of intrigue and unease, anomalous beauty that captivates. “A photograph”, Arbus said, “is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.”

Natura Morta

MORANDI

Morandi was unassuming, in life and in art. Born in Bologna, he lived on the same street, in a modest apartment with his three sisters, from the age of 19 until his death at 73, and rarely left the city. As a young man he experimented with the vogues of the day, but quickly settled into his signature style. Quiet, contemplative, subtle, his still life compositions are experiments in hue and form, as much precursors to the minimalist movement as they are informed by the Italian Old Masters he studied in art school. “I’m a painter”, he said, “of the kind of... composition that communicates a sense of tranquility and privacy, moods which I have always valued above all’.

Giorgio Morandi

GIORGIO MORANDI, 1953. OIL ON CANVAS

Morandi was unassuming, in life and in art. Born in Bologna, he lived on the same street, in a modest apartment with his three sisters, from the age of 19 until his death at 73, and rarely left the city. As a young man he experimented with the vogues of the day, but quickly settled into his signature style. Quiet, contemplative, subtle, his still life compositions are experiments in hue and form, as much precursors to the minimalist movement as they are informed by the Italian Old Masters he studied in art school. “I’m a painter”, he said, “of the kind of... composition that communicates a sense of tranquility and privacy, moods which I have always valued above all’.

Annunciation Triptych ( Merode Altarpiece)

CAMPIN

One of the fathers of the Northern Renaissance, Campin’s Annunciation Triptych is amongst the most celebrated works of Netherlandish painting. A deeply allegorical work, it is architectural in its layout with each panel a window into a different room across the same house. In the central panel, the angel Gabriel is about to tell the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of Jesus. The room Campin painted is based on the living room of the donor who commissioned the painting. This same donor kneels at the doorway in the left hand panel, his wife stood behind them and on the right-hand panel Joseph drills holes in a board in his carpentry studio. The altarpiece was intended for private prayer, a prayer for the hopes of a child for the couple. Campin’s vignettes bring the holy down to earth, the scenes are recognisable in their exquisite detail but otherworldly in their figures.

Robert Campin

ROBERT CAMPIN, c.1430. OIL ON OAK

One of the fathers of the Northern Renaissance, Campin’s Annunciation Triptych is amongst the most celebrated works of Netherlandish painting. A deeply allegorical work, it is architectural in its layout with each panel a window into a different room across the same house. In the central panel, the angel Gabriel is about to tell the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of Jesus. The room Campin painted is based on the living room of the donor who commissioned the painting. This same donor kneels at the doorway in the left hand panel, his wife stood behind them and on the right-hand panel Joseph drills holes in a board in his carpentry studio. The altarpiece was intended for private prayer, a prayer for the hopes of a child for the couple. Campin’s vignettes bring the holy down to earth, the scenes are recognisable in their exquisite detail but otherworldly in their figures.

Mappa

BOETTI

Boetti’s conceptual tapestries were woven by the same Afghan weavers he had maintained a relationship with since the early 70s. The Mappa series was his crowning achievement, a work in which Boetti ‘did nothing, chose nothing, in the sense that the world is made as it is, not as I designed it, the flags are those that exist, and I did not design them. In short, I did absolutely nothing; when the basic idea, the concept, emerges, everything else requires no choosing.’ The one element not already dictated was the color of the ocean, and for this Boetti allowed the Afghan weavers, living in a landlocked country, to choose this, with wonderfully varied results. Boetti’s works are profoundly simple and yet speak to a bigger idea, of a unified world of color and beauty.

Alighiero Boetti

ALIGHIERO BOETTI, 1991. EMBROIDERY ON COTTON

Boetti’s conceptual tapestries were woven by the same Afghan weavers he had maintained a relationship with since the early 70s. The Mappa series was his crowning achievement, a work in which Boetti ‘did nothing, chose nothing, in the sense that the world is made as it is, not as I designed it, the flags are those that exist, and I did not design them. In short, I did absolutely nothing; when the basic idea, the concept, emerges, everything else requires no choosing.’ The one element not already dictated was the color of the ocean, and for this Boetti allowed the Afghan weavers, living in a landlocked country, to choose this, with wonderfully varied results. Boetti’s works are profoundly simple and yet speak to a bigger idea, of a unified world of color and beauty.

Transfigurations

VERUSCHKA

Not all is as it seems in Veruschka's world, almost nothing in fact. Beginning her career in the 60s as the first German Supermodel and Richard Avedon's long time muse, appearing in Antioni's masterpiece Blow-Up. By the start of the 70s, she had rejected the aristocratic, high-fashion world she was born into and instead became an outsider artist, exploring nature, gender and performance in her body work. Painting her body, she hides against walls, windows, skies, trees and the world around her. She exists as a metaphor and natural organism. Many artists use their body as a medium, but Veruschka uses her body as the canvas. Her work compels you to search for her, to see her in whatever form she dictates. She is all of us and none, mother earth and dust. The aesthetic figure Veruschka refuses to be a projection of beauty’s ideals, she rejects the objectification of her past career by becoming one with the natural objects around her.

Veruschka

VERUSCHKA, c.1972

Not all is as it seems in Veruschka's world, almost nothing in fact. Beginning her career in the 60s as the first German Supermodel and Richard Avedon's long time muse, appearing in Antioni's masterpiece Blow-Up. By the start of the 70s, she had rejected the aristocratic, high-fashion world she was born into and instead became an outsider artist, exploring nature, gender and performance in her body work. Painting her body, she hides against walls, windows, skies, trees and the world around her. She exists as a metaphor and natural organism. Many artists use their body as a medium, but Veruschka uses her body as the canvas. Her work compels you to search for her, to see her in whatever form she dictates. She is all of us and none, mother earth and dust. The aesthetic figure Veruschka refuses to be a projection of beauty’s ideals, she rejects the objectification of her past career by becoming one with the natural objects around her.

Apocalypse Now

WOOL

In the shadow of the 1987 Black Monday stock market crash, Wool’s Apocalypse Now became the painting of the decade. Taking the quotation from Captain Colby’s letter home in Francis Ford Coppola's war epic, Wool distorts the phrase, removes the emotion or madness inherent in the original and presents with telegraphic urgency. By removing punctuation, correct spacing and line alignment, he forces the view to work to translate the text into a coherent phrase. Wool’s piece is cold and direct, a hiccup in the comprehension adding to a feeling of the untethered. He captures the fear and euphoria of the 1980s, and of the periods that have come after by combining a dark sense of unease with high-flying success.

Christopher Wool

CHRISTOPHER WOOL, 1987. ALKYD AND FLASHE ON STEEL AND ALUMINUM

In the shadow of the 1987 Black Monday stock market crash, Wool’s Apocalypse Now became the painting of the decade. Taking the quotation from Captain Colby’s letter home in Francis Ford Coppola's war epic, Wool distorts the phrase, removes the emotion or madness inherent in the original and presents with telegraphic urgency. By removing punctuation, correct spacing and line alignment, he forces the view to work to translate the text into a coherent phrase. Wool’s piece is cold and direct, a hiccup in the comprehension adding to a feeling of the untethered. He captures the fear and euphoria of the 1980s, and of the periods that have come after by combining a dark sense of unease with high-flying success.

Cut Piece

ONO

Sat alone on a stage robed in black, with a pair of scissors placed beside her, Yoko Ono invited the audience to come up and cut away pieces of her clothing one by one. The resulting performance piece is now regarded as a pioneering work for the genre, and one of the foundational artworks of both the Fluxus movement and contemporary performance art. In ‘Cut Piece’, the distinction between audience and artwork disappears, no longer can we passively look at a piece of art, instead we have to be an active player in its creation. In this case, Ono makes the audience engage in a violent disrobing, using shears to reveal the female body and as such questioning our passivity when looking at painted or photographed nude works. Ono challenges us to become responsible viewers across all art, to no longer see a separation between the canvas and ourselves but understand that our viewership is inherent to art's existence.

Yoko Ono

YOKO ONO, 1964.

Sat alone on a stage robed in black, with a pair of scissors placed beside her, Yoko Ono invited the audience to come up and cut away pieces of her clothing one by one. The resulting performance piece is now regarded as a pioneering work for the genre, and one of the foundational artworks of both the Fluxus movement and contemporary performance art. In ‘Cut Piece’, the distinction between audience and artwork disappears, no longer can we passively look at a piece of art, instead we have to be an active player in its creation. In this case, Ono makes the audience engage in a violent disrobing, using shears to reveal the female body and as such questioning our passivity when looking at painted or photographed nude works. Ono challenges us to become responsible viewers across all art, to no longer see a separation between the canvas and ourselves but understand that our viewership is inherent to art's existence.

Ophelia

MILLAIS

John Everett Millais sat for eleven hours a day, six days a week, for five months on the banks of the Hogsmill River in order to capture the backdrop for Ophelia, possibly the epitome of the Pre-Raphaelite ideal. The vulnerable woman was a popular subject within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), but none more so than Shakespeare’s wretched, tragic Ophelia - fated to die by her own mad hand, thanks to the actions of the despicable Prince Hamlet. Something of the madness of Ophelia’s tale presumably seized Millais, for his desire to paint her drove him to desperation - eventually building a weatherproofed hut in order to survive the winter’s painting. Using this desperation, Millais succeeded in his task - creating an immaculately detailed, brightly coloured and faithful truth of nature, contrasted sadly against the pale solemnity of the drowned Ophelia.

John Everett Millais

JOHN EVERETT MILLAIS, 1952. OIL ON CANVAS

John Everett Millais sat for eleven hours a day, six days a week, for five months on the banks of the Hogsmill River in order to capture the backdrop for Ophelia, possibly the epitome of the Pre-Raphaelite ideal. The vulnerable woman was a popular subject within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), but none more so than Shakespeare’s wretched, tragic Ophelia - fated to die by her own mad hand, thanks to the actions of the despicable Prince Hamlet. Something of the madness of Ophelia’s tale presumably seized Millais, for his desire to paint her drove him to desperation - eventually building a weatherproofed hut in order to survive the winter’s painting. Using this desperation, Millais succeeded in his task - creating an immaculately detailed, brightly coloured and faithful truth of nature, contrasted sadly against the pale solemnity of the drowned Ophelia.

Paysage Aux Végétations

DUBUFFET

Jean Dubuffet was well into middle age when his life’s work began. An occasional artist, winemaker and scholar, Dubuffet rejected anything that confined him as he strove for knowledge and traveled the world. He immersed himself in the study of noise music, of ancient languages, lost wisdom and poetry, picking up and putting down the paintbrush every decade or so. The eventual progenitor of the art brut (raw art) movement finally found his calling in painting for the first time at the age of 41. Experimenting with non-traditional new materials, he incorporated mud, sand, gravel, and, notably, plant matter into his compositions. He became a geologist of sorts, studying the vegetable/mineral representations of the organic landscapes he would have simply painted ten years earlier. From these experiments eventually came art brut; a movement born of Dubuffet's embracing of the art of children and the mentally ill. He argued that the concept of ‘culture’ both assimilated and subsequently disempowered each successive evolution in art. The only outcome could be the death of true expression, but not for art brut — only they could resist culture, because the artists themselves were unable to be assimilated.

Jean Dubuffet

JEAN DUBUFFET, 1952. OIL ON MASONITE

Jean Dubuffet was well into middle age when his life’s work began. An occasional artist, winemaker and scholar, Dubuffet rejected anything that confined him as he strove for knowledge and traveled the world. He immersed himself in the study of noise music, of ancient languages, lost wisdom and poetry, picking up and putting down the paintbrush every decade or so. The eventual progenitor of the art brut (raw art) movement finally found his calling in painting for the first time at the age of 41. Experimenting with non-traditional new materials, he incorporated mud, sand, gravel, and, notably, plant matter into his compositions. He became a geologist of sorts, studying the vegetable/mineral representations of the organic landscapes he would have simply painted ten years earlier. From these experiments eventually came art brut; a movement born of Dubuffet's embracing of the art of children and the mentally ill. He argued that the concept of ‘culture’ both assimilated and subsequently disempowered each successive evolution in art. The only outcome could be the death of true expression, but not for art brut — only they could resist culture, because the artists themselves were unable to be assimilated.