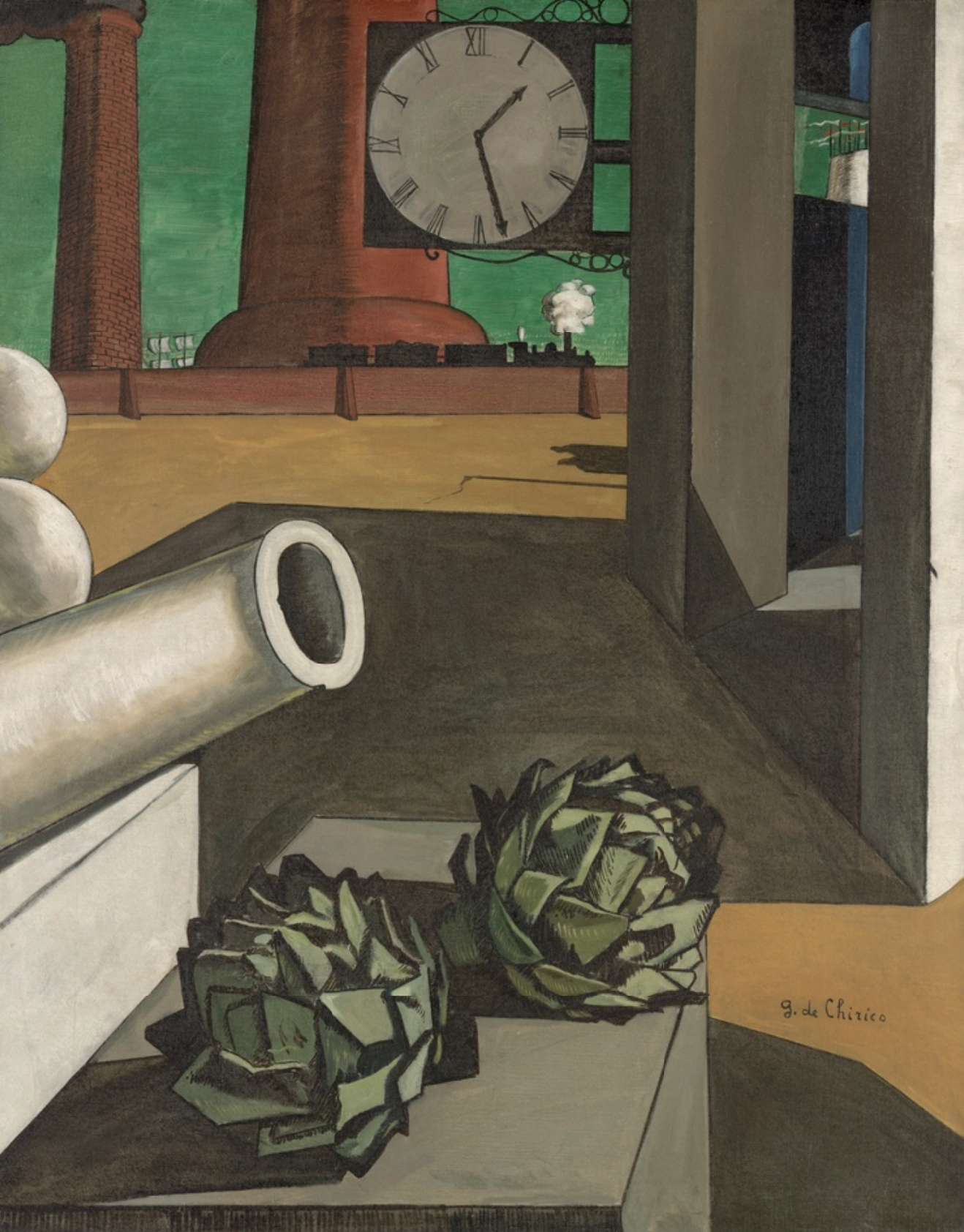

The Philosopher’s Conquest

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO

Ten years before Dalí put dreams to canvas or Magritté created works of visual and intellectual illusion, the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico was painting definitively surrealist works. His art combines classicism with the avant-garde, creating paintings that at first glance could be read as naïve landscapes or simple still lives but on further inspection become disturbing and disquieting compositions of implausible juxtaposition. Here, time and space themselves subtly warp; the clock reads 1:30, but the shadows are long as if late or early in the day. A steam train rides by in the background, it’s shape proportionate to the foreground but it is dwarfed by two pillars behind it, throwing our perspective and sense of scale into disarray. Two cannonballs emerge from the corner, and seem to be balanced perfectly atop each other with no sense of precariousness. Yet all of these oddities dwarf under the most surreal element of all - the combination of objects. This is a palazzo of dreams, populated with incongruous matter that create a connection to the subconscious, but fail to make any rational sense together.

Giorgio de Chirico

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO, 1914. OIL ON CANVAS.

Ten years before Dalí put dreams to canvas or Magritté created works of visual and intellectual illusion, the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico was painting definitively surrealist works. His art combines classicism with the avant-garde, creating paintings that at first glance could be read as naïve landscapes or simple still lives but on further inspection become disturbing and disquieting compositions of implausible juxtaposition. Here, time and space themselves subtly warp; the clock reads 1:30, but the shadows are long as if late or early in the day. A steam train rides by in the background, it’s shape proportionate to the foreground but it is dwarfed by two pillars behind it, throwing our perspective and sense of scale into disarray. Two cannonballs emerge from the corner, and seem to be balanced perfectly atop each other with no sense of precariousness. Yet all of these oddities dwarf under the most surreal element of all - the combination of objects. This is a palazzo of dreams, populated with incongruous matter that create a connection to the subconscious, but fail to make any rational sense together.

Excavation

WILLEM DE KOONING

De Kooning spent months finding the heart of an artwork. Meticulously building up thick layers of paint and then meticulously scraping them away, he worked as an excavator of beauty and truth. The title of this artwork, then, is fitting, and when it was completed it was his largest canvas to date. Inspired by an image of a woman working in a rice field from a Neo-realist Italian film, the organic forms and calligraphic lines seem to dance and flutter across the space, they’re movements revealing a hidden world of colour that lurks below. On initial viewing, the work seems wholly abstract, but as you get closer and begin to learn that language of his brushstrokes what was once a field of white becomes an orchestra of faces, objects, animals and bones. Eyes suddenly emerge out of vastness and fish swim through a squirming swathe of bodies - de Kooning forces the viewer to take on the same role as himself, and we become excavators of his vision the longer we look.

Willem de Kooning

WILLEM DE KOONING, 1950. OIL ON CANVAS.

De Kooning spent months finding the heart of an artwork. Meticulously building up thick layers of paint and then meticulously scraping them away, he worked as an excavator of beauty and truth. The title of this artwork, then, is fitting, and when it was completed it was his largest canvas to date. Inspired by an image of a woman working in a rice field from a Neo-realist Italian film, the organic forms and calligraphic lines seem to dance and flutter across the space, they’re movements revealing a hidden world of colour that lurks below. On initial viewing, the work seems wholly abstract, but as you get closer and begin to learn that language of his brushstrokes what was once a field of white becomes an orchestra of faces, objects, animals and bones. Eyes suddenly emerge out of vastness and fish swim through a squirming swathe of bodies - de Kooning forces the viewer to take on the same role as himself, and we become excavators of his vision the longer we look.

The Entombment of Christ

CARAVAGGIO

A masterpiece of falling action, the painting moves from hysteria to calm as Christ’s body is lowered. Mary of Cleophas, in the top right, gestures in desperation towards heaven, her upwards eyes filled with longing. Below her, Mary Magdalene’s open palm faces towards Christ, as if pushing him to his resting place and, at the bottom left, Christ’s limp hand touches the burial stone upon which he will be placed. For all of it aesthetic beauty, representational splendour and allegorical brilliance, perhaps most remarkable is that Caravaggio tells the story of Jesus Christ in hand placement alone - mankind comes into contact with heaven, and God comes to touch the earth. This was the altarpiece of a chapel, and each day the priest would offer sacrament in front of it. This action, raising the body and blood of christ upwards, served as a perfect mirror to the entombment happening behind him, imbuing the work and the story with new life and relevance as long as it remains on view.

Caravaggio

CARAVAGGIO, c.1603. OIL ON CANVAS.

A masterpiece of falling action, the painting moves from hysteria to calm as Christ’s body is lowered. Mary of Cleophas, in the top right, gestures in desperation towards heaven, her upwards eyes filled with longing. Below her, Mary Magdalene’s open palm faces towards Christ, as if pushing him to his resting place and, at the bottom left, Christ’s limp hand touches the burial stone upon which he will be placed. For all of it aesthetic beauty, representational splendour and allegorical brilliance, perhaps most remarkable is that Caravaggio tells the story of Jesus Christ in hand placement alone - mankind comes into contact with heaven, and God comes to touch the earth. This was the altarpiece of a chapel, and each day the priest would offer sacrament in front of it. This action, raising the body and blood of christ upwards, served as a perfect mirror to the entombment happening behind him, imbuing the work and the story with new life and relevance as long as it remains on view.

Portrait of a Living Room

DOROTHY VARIAN

Dorothy Varian was part of a group of female artists from Woodstock, New York, who despite success and prominence in their lifetime, have faded into obscurity. Classically trained in Paris, she exhibited in the capital throughout the 1920s at influential and regarded galleries, but her work was perhaps too straightforward, and not radical enough, to make significant dents in a revolutionary period. Her portrait of a living room is finely rendered in detail and elegantly composed. We are immediately situated in the domestic home, peering through an arched opening towards a room in use. It is not on airs, not trying to present itself as more than a humble home, replete with mess and life, the plants in the background imperfectly bending and the coffee table askew. Dorian’s painting is familiar, it speaks to a commonality of American home life that perhaps only a woman in this time was able to conjure. Yet this may be its downfall, it is pleasant and approachable, painted at a time when such qualities were seen within the art world as not just dull, but altogether sinful.

Dorothy Varian

DOROTHY VARIAN, 1944. OIL ON CANVAS.

Dorothy Varian was part of a group of female artists from Woodstock, New York, who despite success and prominence in their lifetime, have faded into obscurity. Classically trained in Paris, she exhibited in the capital throughout the 1920s at influential and regarded galleries, but her work was perhaps too straightforward, and not radical enough, to make significant dents in a revolutionary period. Her portrait of a living room is finely rendered in detail and elegantly composed. We are immediately situated in the domestic home, peering through an arched opening towards a room in use. It is not on airs, not trying to present itself as more than a humble home, replete with mess and life, the plants in the background imperfectly bending and the coffee table askew. Dorian’s painting is familiar, it speaks to a commonality of American home life that perhaps only a woman in this time was able to conjure. Yet this may be its downfall, it is pleasant and approachable, painted at a time when such qualities were seen within the art world as not just dull, but altogether sinful.

Landscape with Figures

MARGUERITE ZORACH

Zorach went against the grain every opportunity she could. Born into a well-to-do California, she escaped to Paris as a teenager to stay with a bohemian aunt and found herself at the centre of a new avant-garde movement that was equally enamoured with her as she was with it. She rejected traditional, academic education and even shunned orthodox art school, instead studying a post-impressionist school that allowed her to develop a unique style with little regard for tradition or societal aesthetic norms. It was there that she met her husband William, who was so beguiled by her art that it extended to her. ‘I just couldn't understand why such a nice girl would paint such wild pictures.’, he later said. Her journey back to America took her through her through Egypt, Palestine, India, Burma, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Korea, and Japan over the course of seven months, and her exposure to multiple worlds is abundantly clear in this painting. The flat planes speak to traditional Japanese art, while the landscape has hints of India, and the figures are distinctly of the Matisse school. She synthesised place and style into a unique voice that drowned out all others.

Marguerite Zorach

MARGUERITE ZORACH, 1913. GOUACHE AND WATERCOLOR ON SILK.

Zorach went against the grain every opportunity she could. Born into a well-to-do California, she escaped to Paris as a teenager to stay with a bohemian aunt and found herself at the centre of a new avant-garde movement that was equally enamoured with her as she was with it. She rejected traditional, academic education and even shunned orthodox art school, instead studying a post-impressionist school that allowed her to develop a unique style with little regard for tradition or societal aesthetic norms. It was there that she met her husband William, who was so beguiled by her art that it extended to her. ‘I just couldn't understand why such a nice girl would paint such wild pictures.’, he later said. Her journey back to America took her through her through Egypt, Palestine, India, Burma, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Korea, and Japan over the course of seven months, and her exposure to multiple worlds is abundantly clear in this painting. The flat planes speak to traditional Japanese art, while the landscape has hints of India, and the figures are distinctly of the Matisse school. She synthesised place and style into a unique voice that drowned out all others.

The Red Armchair

PABLO PICASSO

A portrait of love and deception, Picasso’s ‘The Red Armchair’ features his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter as its sole subject. Part of a series of portraits of her, and in each one her physical form takes on the workings of his mind, distorted and changed to become indicative of his emotions and feelings towards not just her but their relationship in general. She is a vessel for Picasso, and he removes her autonomy in his representations, treating her instead as an extension of himself. Here, he takes the foundations of the Cubist philosophy he developed but applies the work of multiple perspective not to still lives but to a human for nearly the first time. It is fitting that the first subject he painted in this was Walter. Her face is shown in duality, both in profile and front-on so that she becomes an embodiment of the double life that Picasso has been living during their affair. She energised the artist, brought an intensity in his colour and form and marked a significant turning point in his development. In this way, we can read her double face as exemplary of a turning point in Picasso, a move from looking one way to seeing things in a whole new light.

Pablo Picasso

PABLO PICASSO, 1931. OIL AND RIPOLIN ON PANEL.

A portrait of love and deception, Picasso’s ‘The Red Armchair’ features his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter as its sole subject. Part of a series of portraits of her, and in each one her physical form takes on the workings of his mind, distorted and changed to become indicative of his emotions and feelings towards not just her but their relationship in general. She is a vessel for Picasso, and he removes her autonomy in his representations, treating her instead as an extension of himself. Here, he takes the foundations of the Cubist philosophy he developed but applies the work of multiple perspective not to still lives but to a human for nearly the first time. It is fitting that the first subject he painted in this was Walter. Her face is shown in duality, both in profile and front-on so that she becomes an embodiment of the double life that Picasso has been living during their affair. She energised the artist, brought an intensity in his colour and form and marked a significant turning point in his development. In this way, we can read her double face as exemplary of a turning point in Picasso, a move from looking one way to seeing things in a whole new light.

Fishing Boats with Hucksters Bargaining for Fish

J. M. W. TURNER

A child prodigy from a working class family who survived an upbringing of tumult and upheaval to become one of Britain’s most celebrated painters, elevate the art of landscape painting to unseen heights and, ultimately, die alone and in squalor - John Mallord William Turner remains as intriguing, appealing, and enigmatic as ever. He is most known for his paintings of the sea, large scale, vivid, dramatic depictions of naval battles, vessels fighting against the elements, and the violent nature of a nautical life. It has been said that Turner’s paintings capture all that could be said about the sea, and his sweeping scenes play out in visceral detail. Large skies illuminate danger and fury and Turner, like so few others, captured the truthful moods of nature in their wonder and variety. This work is in some ways unusual, there is lightness to it, a drama plays out with low stakes as a bright sky appears through clouds and the sailors are engaged in commerce with a nearby peddler. Yet, behind the sails, a steam boat appears in the distance - the battle depicted here is not one of violence, but of the past reckoning with a fast approaching, modern, industrial future.

J. M. W. Turner

J. M. W. TURNER, c.1838. OIL ON CANVAS.

A child prodigy from a working class family who survived an upbringing of tumult and upheaval to become one of Britain’s most celebrated painters, elevate the art of landscape painting to unseen heights and, ultimately, die alone and in squalor - John Mallord William Turner remains as intriguing, appealing, and enigmatic as ever. He is most known for his paintings of the sea, large scale, vivid, dramatic depictions of naval battles, vessels fighting against the elements, and the violent nature of a nautical life. It has been said that Turner’s paintings capture all that could be said about the sea, and his sweeping scenes play out in visceral detail. Large skies illuminate danger and fury and Turner, like so few others, captured the truthful moods of nature in their wonder and variety. This work is in some ways unusual, there is lightness to it, a drama plays out with low stakes as a bright sky appears through clouds and the sailors are engaged in commerce with a nearby peddler. Yet, behind the sails, a steam boat appears in the distance - the battle depicted here is not one of violence, but of the past reckoning with a fast approaching, modern, industrial future.

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz

AMEDEO MODIGLIANI

Two friends shared the commonality of context, but a radical difference in philosophy. Amedeo Modigliani and Jacques Lipchitz had arrived in Paris at the same age, and were two young Jewish men frequenting the same literary circles who became very close friends. Lipchitz exemplified a industriousness, working as a sculptor he was exacting and prolific, single-minded in his ambition as he became of Cubism’s most significant sculptors. Modigliani, on the other want, was the archetypal bohemian; a terrible drunk, he lived a fast life of debauchery and worked with speed, looseness, and the confidence of his brilliance. This is a rare work of Modigliani’s, not only for being one of the few double portraits he ever painted in his career, but also for the amount of time he spent on it. Lipchitz had recently come into some money when he commissioned the work of him and his wife from this friend. Modigliani’s charged only ten francs and painted the work in a single sitting. Lipchitz, wanting to help Modigliani financially, encouraged him to keep working on the painting for two weeks, paying him for it, despite Modigliani’s objections. The finished result is a work of delicate, assured beauty, not as loose as most of his canvases but retaining all the disquiet harmony.

Amadeo Modigliani

AMADEO MODIGLIANI, 1916. OIL ON CANVAS.

Two friends shared the commonality of context, but a radical difference in philosophy. Amedeo Modigliani and Jacques Lipchitz had arrived in Paris at the same age, and were two young Jewish men frequenting the same literary circles who became very close friends. Lipchitz exemplified a industriousness, working as a sculptor he was exacting and prolific, single-minded in his ambition as he became of Cubism’s most significant sculptors. Modigliani, on the other want, was the archetypal bohemian; a terrible drunk, he lived a fast life of debauchery and worked with speed, looseness, and the confidence of his brilliance. This is a rare work of Modigliani’s, not only for being one of the few double portraits he ever painted in his career, but also for the amount of time he spent on it. Lipchitz had recently come into some money when he commissioned the work of him and his wife from this friend. Modigliani’s charged only ten francs and painted the work in a single sitting. Lipchitz, wanting to help Modigliani financially, encouraged him to keep working on the painting for two weeks, paying him for it, despite Modigliani’s objections. The finished result is a work of delicate, assured beauty, not as loose as most of his canvases but retaining all the disquiet harmony.

Untitled

TANAKA ATSUKO

Tanaka Atsuko was a member of the Gutai Art Association, amongst the most famous and significant avant-garde art movements in 20th century Japan. Their guiding credo was to explore the relationship between spirit, body, and material, and they used every medium possible to do so. They shook the artistic foundations of post-war Japan with radical interventions and performance pieces, and as part of a younger influx into the movement, Atsuko became an icon of the radical. In 1952, she created ‘Electric Dress’, a wearable garment of 200 lightbulbs of different colors that at once spoke to the beauty of modernity, the glory of advertising, and served as a metaphor for it’s dangers as the heat and weight of the dress as damaging to the wearer. It became a symbol of the movement, but the fame and celebration it brought caused Atsuko to ultimately abandon Gutai after falling out with it’s founder. The piece, with it’s dazzling concentric circles, can be seen as an interpretation of this ‘Electric Dress’, an experimental and conceptual work brought back to canvas. It loses some of the more tangible commentary but none of the aesthetic power in this translation - it is a reference to a wilder past, a pledge to uphold the philosophy but not fight against the sophistication and wisdom of age.

Tanaka Atsuko

TANAKA ATSUKO, 1964. ENAMEL ON CANVAS.

Tanaka Atsuko was a member of the Gutai Art Association, amongst the most famous and significant avant-garde art movements in 20th century Japan. Their guiding credo was to explore the relationship between spirit, body, and material, and they used every medium possible to do so. They shook the artistic foundations of post-war Japan with radical interventions and performance pieces, and as part of a younger influx into the movement, Atsuko became an icon of the radical. In 1952, she created ‘Electric Dress’, a wearable garment of 200 lightbulbs of different colors that at once spoke to the beauty of modernity, the glory of advertising, and served as a metaphor for it’s dangers as the heat and weight of the dress as damaging to the wearer. It became a symbol of the movement, but the fame and celebration it brought caused Atsuko to ultimately abandon Gutai after falling out with it’s founder. The piece, with it’s dazzling concentric circles, can be seen as an interpretation of this ‘Electric Dress’, an experimental and conceptual work brought back to canvas. It loses some of the more tangible commentary but none of the aesthetic power in this translation - it is a reference to a wilder past, a pledge to uphold the philosophy but not fight against the sophistication and wisdom of age.

Lot’s Wife

ANN BROCKMAN

In the book of Genesis, we are told the story of two angels who visit Lot, his wife, and children in the sinful city of Sodom. They warn the family of the impending disaster that the iniquity of the place will bring, and to leave right away for their own safety, and not look back in the process. As they flee, Lot’s wife turns back to look at the home she has left behind and, because this directly disobeyed the rule of the angels, she is turned into a pillar of sand. The story has its roots in many mythological tales, with the theme of turning to look back a feature of the fables of ancient cultures. Lot’s wife is never given a name further than this, she is an object of possession and her significance in Genesis is purely to serve as a reminder of the dangers of revealing that which you truly desire. Yet Brockman takes a tired story with an ignored protagonist and elevates into a work of gentle, powerful defiance with deftness and beauty.

Ann Brockman

ANN BROCKMAN, 1942. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the book of Genesis, we are told the story of two angels who visit Lot, his wife, and children in the sinful city of Sodom. They warn the family of the impending disaster that the iniquity of the place will bring, and to leave right away for their own safety, and not look back in the process. As they flee, Lot’s wife turns back to look at the home she has left behind and, because this directly disobeyed the rule of the angels, she is turned into a pillar of sand. The story has its roots in many mythological tales, with the theme of turning to look back a feature of the fables of ancient cultures. Lot’s wife is never given a name further than this, she is an object of possession and her significance in Genesis is purely to serve as a reminder of the dangers of revealing that which you truly desire. Yet Brockman takes a tired story with an ignored protagonist and elevates into a work of gentle, powerful defiance with deftness and beauty.

Sea Gazers

MILTON AVERY

The horizon almost dissolves between shades of blue so subtly different you hardly notice the transition. Two figures sit under umbrellas in serenity and we, the viewer, are voyeurs to a scene of tranquil calm, emphasised by every soft hue and gentle brushstroke. Milton Avery was a master colorist, perhaps the greatest in American history, who could wield a palette into submission and create with shade alone an overwhelming emotion. More often than not, this emotion was one of calm. His work is absent of anxiety or anger, even when showing tumultuous seas or energetic nature, every piece is underscored by a poetic tranquility. So overwhelming is this feeling, it seems as if Avery has a detachment from the world he depicts. That distance is perhaps unsurprising when put into the context of his work. His paintings are wholly figurative and yet they speaks to, and inspired, a burgeoning abstract movement. He existed between movements, to figurative for the abstracts and too abstract for the figuratives, and so Avery rose above it all, saw the world unburdened by anything other than the beauty he could find in the everyday around him.

Milton Avery

MILTON AVERY, 1956. OIL ON CANVAS.

The horizon almost dissolves between shades of blue so subtly different you hardly notice the transition. Two figures sit under umbrellas in serenity and we, the viewer, are voyeurs to a scene of tranquil calm, emphasised by every soft hue and gentle brushstroke. Milton Avery was a master colorist, perhaps the greatest in American history, who could wield a palette into submission and create with shade alone an overwhelming emotion. More often than not, this emotion was one of calm. His work is absent of anxiety or anger, even when showing tumultuous seas or energetic nature, every piece is underscored by a poetic tranquility. So overwhelming is this feeling, it seems as if Avery has a detachment from the world he depicts. That distance is perhaps unsurprising when put into the context of his work. His paintings are wholly figurative and yet they speaks to, and inspired, a burgeoning abstract movement. He existed between movements, to figurative for the abstracts and too abstract for the figuratives, and so Avery rose above it all, saw the world unburdened by anything other than the beauty he could find in the everyday around him.

Little Harbor in Normandy

GEORGES BRAQUE

Georges Braque began his career painting landscapes. Inspired by the work of Cézanne, he sought to push the great artist’s philosophy of multiple perspectives to its logical conclusion, and he took up much the same subject matter as his inspiration. That changed, however, after a meeting with Pablo Picasso in 1908, and a discovery that the two artists were approaching the same ideas, philosophies and hopes from radically different origins. Together, they created one of the most significant movements in the history of art - Cubism, and Braque’s landscapes began to be replaced by still life. “In the still-life you have a tactile, I might almost say a manual space.”, said Braque, “In tactile space you measure the distance separating you from the object, whereas in visual space you measure the distance separating things from each other”. Still-life became the subject matter of Cubism and yet the piece here, painted in 1909, and widely regarded as the first fully completed Cubist artwork, shows the artist unable to fully give up his beginnings. The sea and small boats are frenetic with energy, they dance across the canvas and hurtle towards the viewer at full speed. Braque found, early on, a way to make the landscape shrink entirely the distance between the viewer and the piece.

Georges Braque

GEORGES BRAQUE, 1909. OIL ON CANVAS.

Georges Braque began his career painting landscapes. Inspired by the work of Cézanne, he sought to push the great artist’s philosophy of multiple perspectives to its logical conclusion, and he took up much the same subject matter as his inspiration. That changed, however, after a meeting with Pablo Picasso in 1908, and a discovery that the two artists were approaching the same ideas, philosophies and hopes from radically different origins. Together, they created one of the most significant movements in the history of art - Cubism, and Braque’s landscapes began to be replaced by still life. “In the still-life you have a tactile, I might almost say a manual space.”, said Braque, “In tactile space you measure the distance separating you from the object, whereas in visual space you measure the distance separating things from each other”. Still-life became the subject matter of Cubism and yet the piece here, painted in 1909, and widely regarded as the first fully completed Cubist artwork, shows the artist unable to fully give up his beginnings. The sea and small boats are frenetic with energy, they dance across the canvas and hurtle towards the viewer at full speed. Braque found, early on, a way to make the landscape shrink entirely the distance between the viewer and the piece.

Ready-to-Wear

STUART DAVIS

The colors do not mix. There is no gentle dispersion of light, or gradual movement from brightness to darkness. The forms overlap, they interrupt and inject and each ultimately stands alone. Yet the colors and the shapes come together to create something harmonious, something beautiful, something greater than the sum of its parts. Stuart Davis was an optimist. He saw the inventions and attitudes of the modern age as things worthy of celebration, and he incorporated their language into his work. ‘Ready-to-Wear’ is an ode to mass produced fashion, to the innovation and repetition that leads to a garment that, when in the hands of the wearer, becomes almost impossible unique. The forms in the painting may even be these patterns, component parts that when stitched together create something new, and the cross of white in the corner are the scissors themselves, a makers mark hiding in the artwork. Yet ‘Ready-to-Wear’ as a title also speaks to Davis’ process - simple primary colours, painted straight from the tube, allow more freedom and energy to exist on the canvas through movement and form. Davis tells us in both concept and practice that the modern age allows a new energy, and if we harness it correctly, that energy can open new worlds.

Stuart David

STUART DAVIS, 1955. OIL ON CANVAS.

The colors do not mix. There is no gentle dispersion of light, or gradual movement from brightness to darkness. The forms overlap, they interrupt and inject and each ultimately stands alone. Yet the colors and the shapes come together to create something harmonious, something beautiful, something greater than the sum of its parts. Stuart Davis was an optimist. He saw the inventions and attitudes of the modern age as things worthy of celebration, and he incorporated their language into his work. ‘Ready-to-Wear’ is an ode to mass produced fashion, to the innovation and repetition that leads to a garment that, when in the hands of the wearer, becomes almost impossible unique. The forms in the painting may even be these patterns, component parts that when stitched together create something new, and the cross of white in the corner are the scissors themselves, a makers mark hiding in the artwork. Yet ‘Ready-to-Wear’ as a title also speaks to Davis’ process - simple primary colours, painted straight from the tube, allow more freedom and energy to exist on the canvas through movement and form. Davis tells us in both concept and practice that the modern age allows a new energy, and if we harness it correctly, that energy can open new worlds.

Forest and Sun

MAX ERNST

As a young child, Max Ernst stood in-front of German forests and felt an overwhelming sense of fear and wonder. The wood loomed over him with ‘delight and oppression and what the Romantics called ‘emotion in the face of Nature.’’, said Ernst many years later. He captures this spiritual relationship, one of feeling part of the invisible world that hides within nature, in this painting, produced during one of his most prolific and inspired periods. Using his radical technique of ‘frottage’, whereby he rubbed pencil, charcoal, or pigment creates a relief from natural matter behind the paper. Ernst created a forest out of wood. The effect of petrified trees came from bark itself, folded and adapted to form the shape that Ernst desired. In this way, as much as the painting deals with Ernst’s feelings of smallness in the face of grand nature, it also represents a conquering of the very elements that caused him feelings of such oppression as a child.

Max Ernst

MAX ERNST, 1927. OIL ON CANVAS.

As a young child, Max Ernst stood in-front of German forests and felt an overwhelming sense of fear and wonder. The wood loomed over him with ‘delight and oppression and what the Romantics called ‘emotion in the face of Nature.’’, said Ernst many years later. He captures this spiritual relationship, one of feeling part of the invisible world that hides within nature, in this painting, produced during one of his most prolific and inspired periods. Using his radical technique of ‘frottage’, whereby he rubbed pencil, charcoal, or pigment creates a relief from natural matter behind the paper. Ernst created a forest out of wood. The effect of petrified trees came from bark itself, folded and adapted to form the shape that Ernst desired. In this way, as much as the painting deals with Ernst’s feelings of smallness in the face of grand nature, it also represents a conquering of the very elements that caused him feelings of such oppression as a child.

Arlésiennes

PAUL GAUGUIN

During a brief and tumultuous stay with Vincent Van Gogh in Arles, Gaugin painted seventeen canvases of rural life. Many of them were scenes that had been painted by Van Gogh previously, and it is in the comparison between the two that we can see the true nature of each artist most clearly. Here, Gauguin paints the Yellow House, right across the road from Vincent’s residence, as four women wrapped in shawls walk the path in front. It is a remarkably deliberate work, lacking the loose spontaneity and explicit emotion of Van Gogh’s. Here, every element is considered not for its realism but for its compositional benefit. Gauguin’s only loyalty is to the final image - he warps space and time, as in the bench that curves upwards against the perspective, he changes faces and poses to create aesthetic balance and beauty, and he changes the shape and placement of objects to draw the eye where he pleases, as in the foreground bush and conical ferns here. The work is a masterpiece of charged repression, hiding mystery and emotion beneath its considered, perfect veneer as if Gauguin presents both the interior and exterior lives of his subject all at once.

Paul Gauguin

PAUL GAUGUIN, 1888. OIL ON CANVAS.

During a brief and tumultuous stay with Vincent Van Gogh in Arles, Gaugin painted seventeen canvases of rural life. Many of them were scenes that had been painted by Van Gogh previously, and it is in the comparison between the two that we can see the true nature of each artist most clearly. Here, Gauguin paints the Yellow House, right across the road from Vincent’s residence, as four women wrapped in shawls walk the path in front. It is a remarkably deliberate work, lacking the loose spontaneity and explicit emotion of Van Gogh’s. Here, every element is considered not for its realism but for its compositional benefit. Gauguin’s only loyalty is to the final image - he warps space and time, as in the bench that curves upwards against the perspective, he changes faces and poses to create aesthetic balance and beauty, and he changes the shape and placement of objects to draw the eye where he pleases, as in the foreground bush and conical ferns here. The work is a masterpiece of charged repression, hiding mystery and emotion beneath its considered, perfect veneer as if Gauguin presents both the interior and exterior lives of his subject all at once.

Weaving

DIEGO RIVERA

Hunched over a loom in total focus, Rivera’s subject balances not just her practice but the story of a nation in her lap. Rivera’s portrait is not just of any weaver but of Luz Jiménez, a master weaver, historian, and as a Nahua woman, part of the largest Indigenous group in Mexico, who became a thought leader and teacher to members of the Mexican Nationalist movement like Rivera. Practicing and passing on the traditional artworks, skills, and languages that she had learnt from her mother and other family members, she became a figure of inspiration to a group of artists who saw her as the embodiment of a pre-colonial Mexico. Many subjects of Rivera and his contemporaries’s paintings came from stories told to them and ideas explained by Jiménez, so by making her the subject and protagonist of a work, he pays a debt to the education she provided.

Diego Rivera

DIEGO RIVERA, 1936. TEMPERA AND OIL ON CANVAS.

Hunched over a loom in total focus, Rivera’s subject balances not just her practice but the story of a nation in her lap. Rivera’s portrait is not just of any weaver but of Luz Jiménez, a master weaver, historian, and as a Nahua woman, part of the largest Indigenous group in Mexico, who became a thought leader and teacher to members of the Mexican Nationalist movement like Rivera. Practicing and passing on the traditional artworks, skills, and languages that she had learnt from her mother and other family members, she became a figure of inspiration to a group of artists who saw her as the embodiment of a pre-colonial Mexico. Many subjects of Rivera and his contemporaries’s paintings came from stories told to them and ideas explained by Jiménez, so by making her the subject and protagonist of a work, he pays a debt to the education she provided.

White Crucifixion

MARC CHAGALL

Chagall’s work is most often associated with vivid color, fantastic subjects rendered in lively brushstrokes, and playful romance. His work is spiritual, drawing on folklore and mythology to explore themes of love, celebration, and, in this case, persecution. White Crucifixion is the first in a series Chagall painted drawing an allegory between the persecution of Jesus Christ and the persecution of the Jewish People under the hands of the Nazis. The color that populated Chagall’s work has all but drained away and in its place are pale greys and empty whites - flashes of fire, and the dye of traditional Jewish robes seem faded, though hanging on in a world that has lost its beauty. Chagall casts Jesus as a Jewish martyr, and in doing so reframes the Christian ideology used by the Nazi Party against them, highlighting the hypocrisy and atrocity of the persecutors, In his depiction of the destruction of villages, violent attacks, and government sanctions, he breathes new life into the most told story of the Western World, finding a pertinent and essential relevance in a time when a caring God must have seemed so far away.

Marc Chagall

MARC CHAGALL, 1938, OIL ON CANVAS.

Chagall’s work is most often associated with vivid color, fantastic subjects rendered in lively brushstrokes, and playful romance. His work is spiritual, drawing on folklore and mythology to explore themes of love, celebration, and, in this case, persecution. White Crucifixion is the first in a series Chagall painted drawing an allegory between the persecution of Jesus Christ and the persecution of the Jewish People under the hands of the Nazis. The color that populated Chagall’s work has all but drained away and in its place are pale greys and empty whites - flashes of fire, and the dye of traditional Jewish robes seem faded, though hanging on in a world that has lost its beauty. Chagall casts Jesus as a Jewish martyr, and in doing so reframes the Christian ideology used by the Nazi Party against them, highlighting the hypocrisy and atrocity of the persecutors, In his depiction of the destruction of villages, violent attacks, and government sanctions, he breathes new life into the most told story of the Western World, finding a pertinent and essential relevance in a time when a caring God must have seemed so far away.

Alka Seltzer

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

Lichtenstein elevated the everyday into the extraordinary. Taking imagery from comic books and advertising, he took the imagery of contemporary existence, often derided and ignored by the public, and by placing on canvas through rigorous and arduous work of hand applying the Benday dots that were the byproduct of mass production from screen-printing, they became works of fine art. Here, the Alka-Seltzer becomes a motif of America, and of modern life in totality. Through graphic design, the glass rendered in high contrast black and white transforms itself from the mundane to the iconic, playing with ideas of renaissance art and religion, but bringing it down into the truth of the common man, depicting an image that feels at once familiar, and through his depiction, altogether foreign. Lichtenstein’s glass brims with excitement, it fizzes and pops with promise of the new, and by isolating the image, he grasps at the universal.

Roy Lichtenstein

ROY LICHTENSTEIN, 1966. GRAPHIC ON PAPER.

Lichtenstein elevated the everyday into the extraordinary. Taking imagery from comic books and advertising, he took the imagery of contemporary existence, often derided and ignored by the public, and by placing on canvas through rigorous and arduous work of hand applying the Benday dots that were the byproduct of mass production from screen-printing, they became works of fine art. Here, the Alka-Seltzer becomes a motif of America, and of modern life in totality. Through graphic design, the glass rendered in high contrast black and white transforms itself from the mundane to the iconic, playing with ideas of renaissance art and religion, but bringing it down into the truth of the common man, depicting an image that feels at once familiar, and through his depiction, altogether foreign. Lichtenstein’s glass brims with excitement, it fizzes and pops with promise of the new, and by isolating the image, he grasps at the universal.

Sky Above Clouds IV

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

Georgia O’Keeffe transformed desert planes into abstract color-fields, turned the flowers that grew in the heat into psychedelic explorations of form and movement, and skulls that dotted the landscapes into eerie motifs of the American Southwest. She was, and remains in the popular imagination, an artist so deeply tied to the land, and particularly that of her adopted New Mexico, that to imagine her is to do in the context of the great American landscape. So it is perhaps surprising that towards the end of her life, she turned her focus to the world above. Flying in planes around the world, she gazed out the window and saw new landscapes made from billowing clouds and horizons dancing in shades of blue made visible in the thin air. Gone are the earth tones of her seminal works, replaced by whites, blues, and peaches in calming expressions of scale. Sky Above Clouds IV was a significant undertaking, measuring more than twenty four feet across. It’s monumental size engulfs and invites us to stop and look, to lean our heads against the window and stare out into the expanse.

Georgia O’Keeffe

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE, 1965. OIL ON CANVAS.

Georgia O’Keeffe transformed desert planes into abstract color-fields, turned the flowers that grew in the heat into psychedelic explorations of form and movement, and skulls that dotted the landscapes into eerie motifs of the American Southwest. She was, and remains in the popular imagination, an artist so deeply tied to the land, and particularly that of her adopted New Mexico, that to imagine her is to do in the context of the great American landscape. So it is perhaps surprising that towards the end of her life, she turned her focus to the world above. Flying in planes around the world, she gazed out the window and saw new landscapes made from billowing clouds and horizons dancing in shades of blue made visible in the thin air. Gone are the earth tones of her seminal works, replaced by whites, blues, and peaches in calming expressions of scale. Sky Above Clouds IV was a significant undertaking, measuring more than twenty four feet across. It’s monumental size engulfs and invites us to stop and look, to lean our heads against the window and stare out into the expanse.

Water Lilies

CLAUDE MONET

An image without context, without time, and without place becomes an image of everything. When Claude Monet purchased a house in the French countryside, he planned to turn the garden into an aesthetic feast for the eyes, and built a small bridge, overlooking a pond filled with water lilies. He would spend the next thirty years, the final of his life, painting this scene in variation and repetition, producing more than 250 images of water lilies. When he began, they were more conventional representations of his garden scene and included the bridge, the surrounding trees, the horizon and a sense of their time and place. Yet by 1906, when this image was painted, he had been working with this subject for a decade and the surroundings began to drop away, the surface of the water and flowers that gently rested on top taking up more and more of the canvas until, as we see here, they became the totality. Nothing else matters in this painting, it is a single instant, a moment of nature untied to a human hand or human conceptions. It is unbridled beauty, without distraction - flowers sit in perfect tension and the reflection of above ripples in abstraction to create an image of a small world existing in infinity.

Claude Monet

CLAUDE MONET, 1906. OIL ON CANVAS.

An image without context, without time, and without place becomes an image of everything. When Claude Monet purchased a house in the French countryside, he planned to turn the garden into an aesthetic feast for the eyes, and built a small bridge, overlooking a pond filled with water lilies. He would spend the next thirty years, the final of his life, painting this scene in variation and repetition, producing more than 250 images of water lilies. When he began, they were more conventional representations of his garden scene and included the bridge, the surrounding trees, the horizon and a sense of their time and place. Yet by 1906, when this image was painted, he had been working with this subject for a decade and the surroundings began to drop away, the surface of the water and flowers that gently rested on top taking up more and more of the canvas until, as we see here, they became the totality. Nothing else matters in this painting, it is a single instant, a moment of nature untied to a human hand or human conceptions. It is unbridled beauty, without distraction - flowers sit in perfect tension and the reflection of above ripples in abstraction to create an image of a small world existing in infinity.