Becoming Las Vegas

Jordan Poletti January 20, 2026

If you take the raised pedestrian bridge from the Statue of Liberty, over the 8 Lane Freeway, with the Arthurian Castle on your right, you will find yourself, after being handed a number of call cards for limo-drivers, sex workers and magicians, in the M&M World of Las Vegas Boulevard…

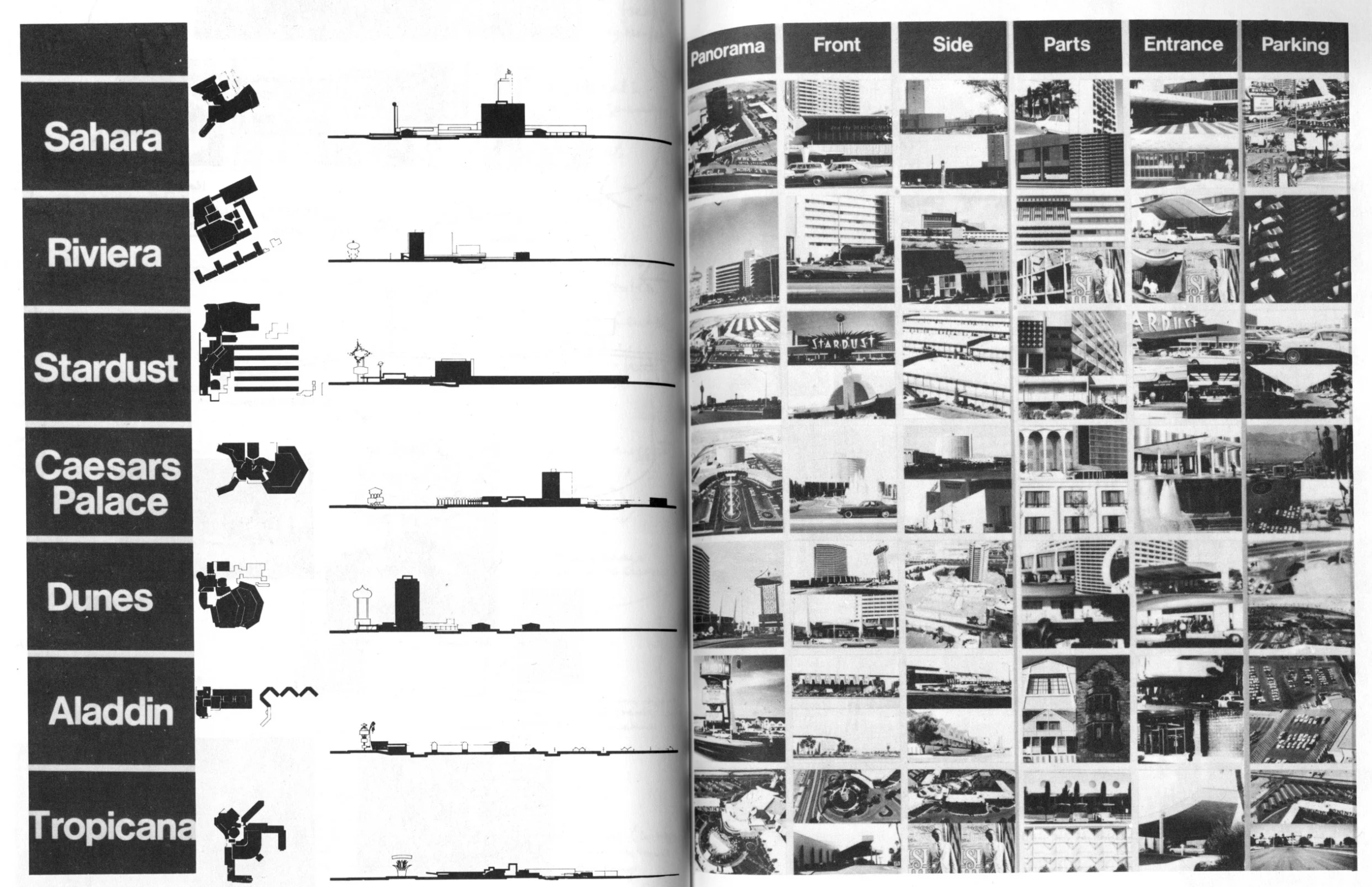

Learning From Las Vegas, Venturi, Brown, Izenous. 1977.

Jordan Poletti January 20, 2026

If you take the raised pedestrian bridge from the Statue of Liberty, over the 8 Lane Freeway, with the Arthurian Castle on your right, you will find yourself, after being handed a number of call cards for limo-drivers, sex workers and magicians, in the M&M World of Las Vegas Boulevard. Nestled neatly into the facade of the MGM Grand, right next to the world's second largest nightclub, owned and operated by a high-end Asian Fusion franchise, it is near identical to the many M&M worlds across the world. If you don't think about it for too long you can make yourself believe you are in Leicester Square, Times Square or Shanghai's People's Square. You wouldn't do this, however, because there is no place in the world you would rather be than right here, the centre of everything and nothingness and very little in between. As you walk through this temple of sugar coated chocolate, peanuts and wafer respectively, you will find yourself no longer in view of the entrance from which you arrived and as you stumble past a 10 foot tube of green candy, you will feel the soft patterned carpet of the MGM Grand Casino. Immediately your tiredness will lift as you breath in oxygenated air and are embraced by the warmth of cigarette smoke and blue-light, epileptic digital screens and the faint click-clack of a roulette ball. If you wanted to return to the M&M world you could not, because the exit has disappeared and it is a one-way porthole that serves a single destination. You will pay a 20 dollar ATM charge to take out not enough money and you will ask yourself the same question that Gorgias, Lao Zing, Descartes, Einstein, David Byrne and Little Simz have asked before you - how did I get here?

If you do not like to gamble, you may well go your whole life without ever visiting Las Vegas. If you do like to gamble, you should go your whole life without ever visiting Las Vegas. But if you have any interest in America, by which I mean modernity, then it is the most important place on Earth. Since its 20th century inception, it has been a city of popular and academic lore, used as muse and message for sin, singularity and separation. A false city who's skyline, Tom Wolfe once wrote, is made up not of buildings or mountains but signage. For the first 100 years of its existence, I suspect the mythification of Las Vegas came from its singularity and its otherness. A city built for a singular purpose of pleasure fulfilment, Versailles it's only equal, and the only legal destination of satiating an American desire for economic self-flagellation. When you arrived on the Strip for 100 years, you encountered novelty, a mirage of simulation and simulacra. Baudrillard's treatise needed no other examples that Las Vegas itself, though only in his later years did he begin to take the city as seriously as he should have. It was Chris Kraus, in her infinite prescience who organised the Chance Conference with Baudrillard in the Nevada desert, placing the father of hyper-modernity in the belly of his patricidal son. It was, he said, and architects, theorist and critics before him, a prototype of the world to come. It's designed disorientation of brash patterns and labyrinthine interiors a far cry from a world still holding onto an enlightenment structure of order and reality. As its neon farms and mob-owned tables were replaced by Eiffel Towers, Pyramids, Gondolas and conglomerates, Las Vegas continued to exist as separate from the rest of the world, updating and adapting to retain its otherness. Where Baudrillard called Disney Land 'miniaturised pleasure of real America', Las Vegas was the miniaturised pleasure of the imaged world. It existed beyond America, a universe unto itself, no longer representing a world but becoming one. It was the only true place in the world, because it cared not for truth, showed there was no truth in the first place, only belief. It offered something separate from daily existence, and this is what gave it its power.

Yet as you stand in the MGM Grand, a bag of M&Ms in your hand, there is little novelty. It feels strangely familiar. You did not get lost on your way here because somehow, the labyrinths of the city felt like you had walked them a hundred times, that the roadmap was embedded in you. This is because the world has caught up with Las Vegas, nearly 100 years later. When Nixon removed the dollar from the Gold Standard in 1971, he made money a simulacra, that which points only to itself, Las Vegas sighed, as it had been doing the same since 1931. Now, it is not just money which is the simulacra but the hyper-reality than Baudrillard talked about has taken is in full force, and Vegas was waiting. On a single junction, outside the M&M world, you can travel through space and time, every corner of the globe and time-period of history. The Statue of Liberty, the Pyramids of Giza, the Eiffel Tower, Caesar's Palace, Medieval Castles. It is no coincidence that the hotels of Vegas are always pointing to something else. They're taking us out of space and time, to a plane not inhabited by context, but a flat circle of shamelessness and instinct. Yet now, this Junction that was once the property of the Nevada desert, exists in the right hand pocket of near ever pair of trousers in the world. We scroll through our feeds and move through time and space. We see a model under the Eiffel Tower and right below it, an aunt by the Sphinx. Between the personal experience we are served ads for hard shell chocolates and pop- ups for daily spins that promise the potential of riches. Brown, Izenour and Venturi told us we must learn from Las Vegas, but instead we have become it. The city understood, long before the rest of the world, that space and time are redundant in the face of desire and satiation. It is the external facade of hyper-reality, of the dissolving of era, country, reality, into a single falsity all while you are crossing that pedestrian bridge above a six lane highway. This is where we are all right now, wavering on the precipice of the M&M World and the Casino beyond it. And we haven't even got inside to gamble yet.

Jordan Poletti is a writer and researcher, focusing on 20th century cultural theory and philosophy.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1155742722?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Filming Othello clip 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

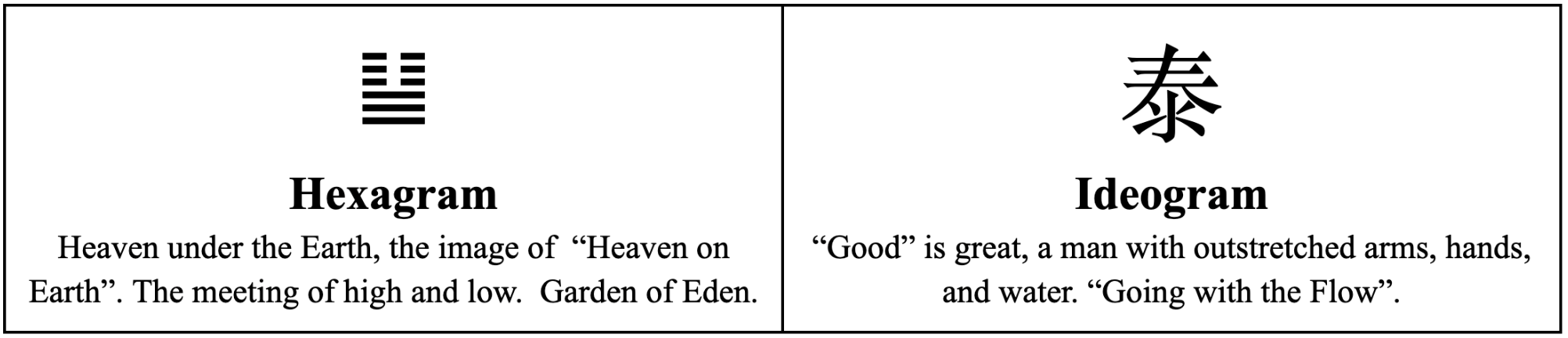

11 Yes (Good) - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 17, 2026

The Low goes and the High comes…

Chris Gabriel January 17, 2026

Judgment

The Low goes and the High comes.

Lines

1

Pull up the tares and the wheat goes with it.

2

Embrace the hard places. Crossing the river, after losing a friend I make it to the middle.

3

Without lows there are no highs. Without going there is no return. It’s tough, but it’s not a problem. Don’t stress. Eat.

4

Fluttering about without wealth. Call on your neighbors, not with demands, but with faith.

5

The Great Emperor marries a commoner.

6

The castle walls have fallen into the moat. No soldiers, so I’ll give my own orders.

Qabalah

“Malkuth is in Kether”

The Ace of Cups and the Ace of Disks.

In this Hexagram, we are once again given an image of something close to the perfection of Heaven: the Prelapsarian World, the Garden of Eden. Unusually here, Heaven, which traditionally remains high, is below the Earth. They are interwoven and unified before the Fall. This is “Heaven on Earth”, but in the text we see that the seeds of decay have been sown, and that this pleasurable condition will not last.

1 The opening line is remarkably close to Christ’s Parable of the Tares in Matthew 13.

29 But he said, Nay; lest while ye gather up the tares, ye root up also the wheat with them.

30 Let both grow together until the harvest: and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, Gather ye together first the tares, and bind them in bundles to burn them: but gather the wheat into my barn.

In this line we see the intermingling of the Low and the High, Matter and Spirit, Earth and Heaven. “Et in Arcadia ego” - even in Paradise, evil has been seeded.

2 The condition of material existence necessitates our affirmation of difficulty. We must find the balance in any situation.

3 A profoundly Solomonic wisdom, there is a time for every thing. One could say the I Ching itself is the “clock” that indicates what sort of “time” it is. As for the affirmation at the end, it is a direct mirror to Solomon’s words in Ecclesiastes 9:7 :

Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works.

4 As in previous hexagrams, we get by with a little help from our friends.

5 In a way, this is another image of the High and Low coming together - the union of the Holy Spirit and Mary, the Divine and the Mundane marrying.

6 By the final line, the condition has decayed. The divine structure has fallen, and individuals must take hold of their own fate.

Qabalistically, this Hexagram illustrates the axiom “Malkuth is in Kether”, base matter exists within the Divine. Before the Fall, God was interwoven with the world. It is the nature of things to change, and accordingly this state of Paradise could never last. Though the state is finite, the hexagram affirms that it does return time after time.

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - December 17, 2025

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Holy Face (1929)

Aldous Huxley January 15, 2026

Good Times are chronic nowadays…

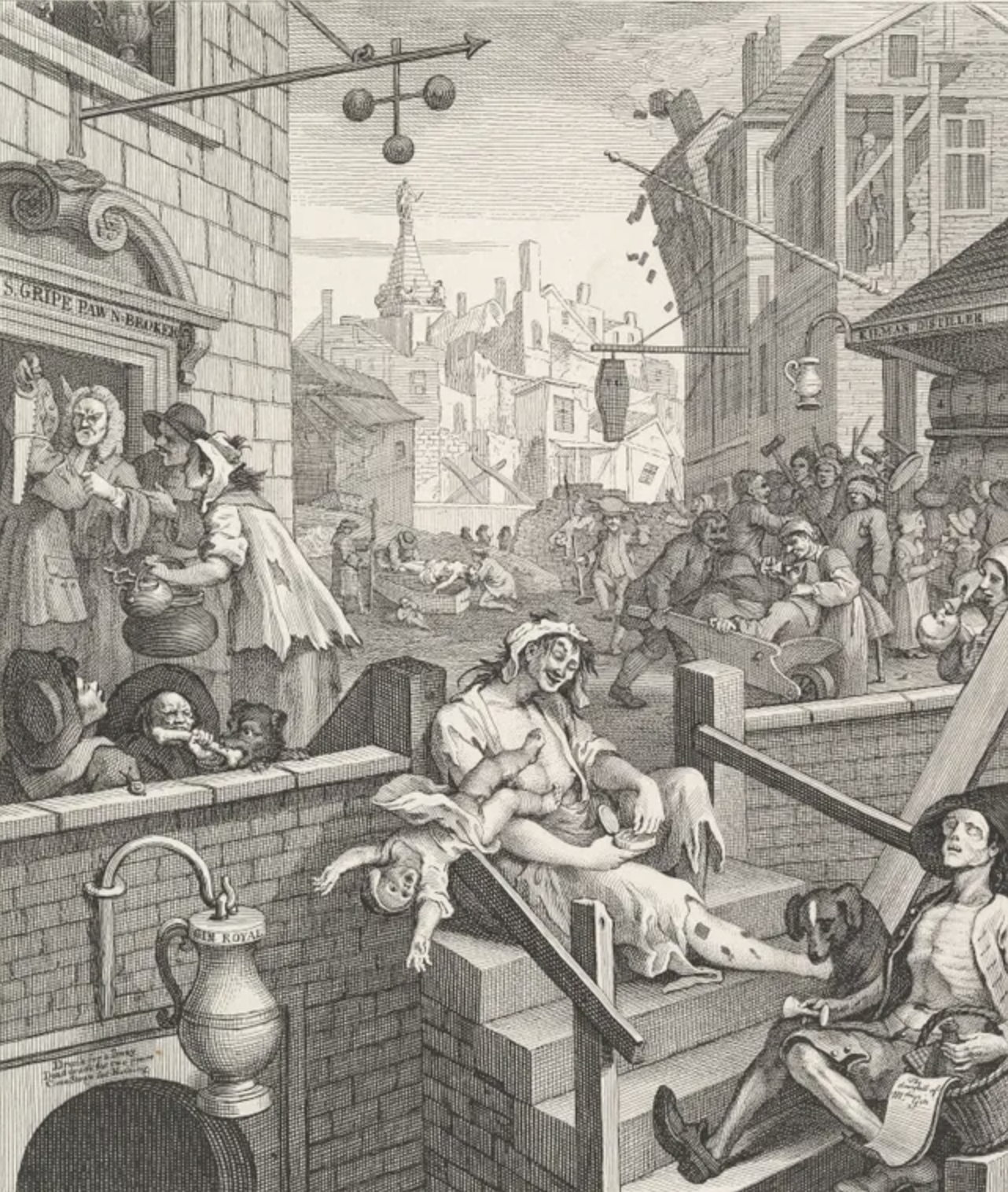

Gin Lane, William Hogarth. 1751.

Before “Brave New World”, Huxley’s seminal and prescient novel about a dystopian future where citizens willingly blind themselves to injustice in favour of ease, Aldous Huxley wrote this essay and chose it to lead one of his earliest collections of his writings. “Holy Face” is a searing critique of the pleasure seeking society, where boredom has become the enemy of existence and we fill our time with fleeting, superficial pleasure in lieu of meaningful thought. This, he argues, is exactly counter to its aim and our desire for quick thrills only creates a more bored society, that must get cheaper and cheaper pleasure to satiate its desire. Huxley, before so many others, saw the pervasiveness of a spiritual emptiness creep into every facet of existence and tried to, by identify it, urge people to reject the systems put upon them as means of control and instead take the reigns of existence, for all its pains and tribulations, as the route to a higher, better life. He uses the religious festival of the Feast of the Holy Face in Lucca, and the acts of devotion occurring around a wooden crucifix bearing the titular ‘Holy Face’, as an example of how we can find deeper meaning in confronting the uncomfortable and the unsettling. After confronting the Holy Face, people instinctively turn back to sunlight, crowds, noise, and the pleasures of the fair outside the church. Huxley sees this instinctive inconsistency as the wiser response. Ordinary people, by embracing both fear and festivity, embody a deeper, unconscious wisdom of life.

Aldous Huxley January 15, 2026

Good Times are chronic nowadays. There is dancing every afternoon, a continuous performance at all the picture-palaces, a radio concert on tap, like gas or water, at any hour of the day or night. The fine point of seldom pleasure is duly blunted. Feasts must be solemn and rare, or else they cease to be feasts. "Like stones of worth they thinly placed are" (or, at any rate, they were in Shakespeare's day, which was the day of Merry England), "or captain jewels in the carconet." The ghosts of these grand occasional jollifications still haunt our modern year. But the stones of worth are indistinguishable from the loud imitation jewelry which now adorns the entire circlet of days. Gems, when they are too large and too numerous, lose all their precious significance; the treasure of an Indian prince is as unimpressive as Aladdin's cave at the pantomime. Set in the midst of the stage diamonds and rubies of modern pleasure, the old feasts are hardly visible. It is only among more or less completely rustic populations, lacking the means and the opportunity to indulge in the modern chronic Good Time, that the surviving feasts preserve something of their ancient glory. Me personally the unflagging pleasures of contemporary cities leave most lugubriously unamused. The prevailing boredom -- for oh, how desperately bored, in spite of their grim determination to have a Good Time, the majority of pleasure-seekers really are! -- the hopeless weariness, infect me. Among the lights, the alcohol, the hideous jazz noises, and the incessant movement I feel myself sinking into deeper and ever deeper despondency. By comparison with a night-club, churches are positively gay. If ever I want to make merry in public, I go where merry-making is occasional and the merriment, therefore, of genuine quality; I go where feasts come rarely.

For one who would frequent only the occasional festivities, the great difficulty is to be in the right place at the right time. I have traveled through Belgium and found, in little market towns, kermesses that were orgiastic like the merry-making in a Breughel picture. But how to remember the date? And how, remembering it, to be in Flanders again at the appointed time? The problem is almost insoluble. And then there is Frogmore. The nineteenth-century sculpture in the royal mausoleum is reputed to be the most amazing of its amazing kind. I should like to see Frogmore. But the anniversary of Queen Victoria's death is the only day in the year when the temple is open to the public. The old queen died, I believe, in January. But what was the precise date? And, if one enjoys the blessed liberty to be elsewhere, how shall one reconcile oneself to being in England at such a season? Frogmore, it seems, will have to remain unvisited. And there are many other places, many other dates and days, which, alas, I shall always miss. I must even be resignedly content with the few festivities whose times I can remember and whose scene coincides, more or less, with that of my existence in each particular portion of the year.

One of these rare and solemn dates which I happen never to forget is September the thirteenth. It is the feast of the Holy Face of Lucca. And since Lucca is within thirty miles of the seaside place where I spend the summer, and since the middle of September is still serenely and transparently summer by the shores of the Mediterranean, the feast of the Holy Face is counted among the captain jewels of my year. At the religious function and the ensuing fair I am, each September, a regular attendant.

"By the Holy Face of Lucca!" It was William the Conqueror's favorite oath. And if I were in the habit of cursing and swearing, I think it would also be mine. For it is a fine oath, admirable both in form and substance. "By the Holy Face of Lucca!" In whatever language you pronounce them, the words reverberate, they rumble with the rumbling of genuine poetry. And for any one who has ever seen the Holy Face, how pregnant they are with power and magical compulsion! For the Face, the Holy Face of Lucca, is certainly the strangest, the most impressive thing of its kind I have ever seen.

Imagine a huge wooden Christ, larger than life, not naked, as in later representations of the Crucifixion, but dressed in a long tunic, formally fluted with stiff Byzantine folds. The face is not the face of a dead, or dying, or even suffering man. It is the face of a man still violently alive, and the expression of its strong features is stern, is fierce, is even rather sinister. From the dark sockets of polished cedar wood two yellowish tawny eyes, made, apparently, of some precious stone, or perhaps of glass, stare out, slightly squinting, with an unsleeping balefulness. Such is the Holy Face. Tradition affirms it to be a true, contemporary portrait. History establishes the fact that it has been in Lucca for the best part of twelve hundred years. It is said that a rudderless and crewless ship miraculously brought it from Palestine to the beaches of Luni. The inhabitants of Sarzana claimed the sacred flotsam; but the Holy Face did not wish to go to Sarzana. The oxen harnessed to the wagon in which it had been placed were divinely inspired to take the road to Lucca. And at Lucca the Face has remained ever since, working miracles, drawing crowds of pilgrims, protecting and at intervals failing to protect the city of its adoption from harm. Twice a year, at Easter time and on the thirteenth of September, the doors of its little domed tabernacle in the cathedral are thrown open, the candles are lighted, and the dark and formidable image, dressed up for the occasion in a jeweled overall and with a glittering crown on its head, stares down -- with who knows what mysterious menace in its bright squinting eyes? -- on the throng of its worshipers.

The official act of worship is a most handsome function. A little after sunset a procession of clergy forms up in the church of San Frediano. In the ancient darkness of the basilica a few candles light up the liturgical ballet. The stiff embroidered vestments, worn by generations of priests and from which the heads and hands of the present occupants emerge with an air of almost total irrelevance (for it is the sacramental carapace that matters; the little man who momentarily fills it is without significance), move hieratically hither and thither through the rich light and the velvet shadows. Under his baldaquin the jeweled old archbishop is a museum specimen. There is a forest of silvery mitres, spear-shaped against the darkness (bishops seem to be plentiful in Lucca). The choir boys wear lace and scarlet. There is a guard of halberdiers in a gaudily-pied medieval uniform. The ritual charade is solemnly danced through. The procession emerges from the dark church into the twilight of the streets. The municipal band strikes up loud inappropriate music. We hurry off to the cathedral by a short cut to take our places for the function.

“Oh, how desperately bored, in spite of their grim determination to have a Good Time, the majority of pleasure-seekers really are!”

The Holy Face has always had a partiality for music. Yearly, through all these hundreds of years, it has been sung to and played at, it has been treated to symphonies, cantatas, solos on every instrument. During the eighteenth century the most celebrated castrati came from the ends of Italy to warble to it; the most eminent professors of the violin, the flute, the oboe, the trombone scraped and blew before its shrine. Paganini himself, when he was living in Lucca in the court of Elisa Bonaparte, performed at the annual concerts in honor of the Face. Times have changed, and the image must now be content with local talent and a lower standard of musical excellence. True, the good will is always there; the Lucchesi continue to do their musical best; but their best is generally no more nor less than just dully creditable. Not always, however. I shall never forget what happened during my first visit to the Face. The musical program that year was ambitious. There was to be a rendering, by choir and orchestra, of one of those vast oratorios which the clerical musician, Dom Perosi, composes in a strange and rather frightful mixture of the musical idioms of Palestrina, Wagner, and Verdi. The orchestra was enormous; the choir was numbered by the hundred; we waited in pleased anticipation for the music to begin. But when it did begin, what an astounding pandemonium! Everybody played and sang like mad, but without apparently any reference to the playing and singing of anybody else. Of all the musical performances I have ever listened to it was the most Manchester-Liberal, the most Victorian-democratic. The conductor stood in the midst of them waving his arms; but he was only a constitutional monarch -- for show, not use. The performers had revolted against his despotism. Nor had they permitted themselves to be regimented into Prussian uniformity by any soul-destroying excess of rehearsal. Godwin's prophetic vision of a perfectly individualistic concert was here actually realized. The noise was hair-raising. But the performers were making it with so much gusto that, in the end, I was infected by their high spirits and enjoyed the hullabaloo almost as much as they did. That concert was symptomatic of the general anarchy of post-war Italy. Those times are now past. The Fascists have come, bringing order and discipline -- even to the arts. When the Lucchesi play and sing to their Holy Face, they do it now with decorum, in a thoroughly professional and well-drilled manner. It is admirable, but dull. There are times, I must confess, when I regret the loud delirious blaring and bawling of the days of anarchy.

Almost more interesting than the official acts of worship are the unofficial, the private and individual acts. I have spent hours in the cathedral watching the crowd before the shrine. The great church is full from morning till night. Men and women, young and old, they come in their thousands, from the town, from all the country round, to gaze on the authentic image of God. And the image is dark, threatening, and sinister. In the eyes of the worshipers I often detected a certain meditative disquiet. Not unnaturally. For if the face of Providence should really and in truth be like the Holy Face, why, then -- then life is certainly no joke. Anxious to propitiate this rather appalling image of Destiny, the worshipers come pressing up to the shrine to deposit a little offering of silver or nickel and kiss the reliquary proffered to every almsgiver by the attendant priest. For two francs fifty perhaps Fate will be kind. But the Holy Face continues, unmoved, to squint inscrutable menace. Fixed by that sinister regard, and with the smell of incense in his nostrils, the darkness of the church around and above him, the most ordinary man begins to feel himself obscurely a Pascal. Metaphysical gulfs open before him. The mysteries of human destiny, of the future, of the purpose of life oppress and terrify his soul. The church is dark; but in the midst of the darkness is a little island of candlelight. Oh, comfort! But from the heart of the comforting light, incongruously jeweled, the dark face stares with squinting eyes, appalling, balefully mysterious.

But luckily, for those of us who are not Pascal, there is always a remedy. We can always turn our back on the Face, we can always leave the hollow darkness of the church. Outside, the sunlight pours down out of a flawless sky. The streets are full of people in their holiday best. At one of the gates of the city, in an open space beyond the walls, the merry-go-rounds are turning, the steam organs are playing the tunes that were popular four years ago on the other side of the Atlantic, the fat woman's drawers hang unmoving, like a huge forked pennon, in the windless air outside her booth. There is a crowd, a smell, an unceasing noise -- music and shouting, roaring of circus lions, giggling of tickled girls, squealing from the switchback of deliciously frightened girls, laughing and whistling, tooting of cardboard trumpets, cracking of guns in the rifle-range, breaking of crockery, howling of babies, all blended together to form the huge and formless sound of human happiness. Pascal was wise, but wise too consciously, with too consistent a spirituality. For him the Holy Face was always present, haunting him with its dark menace, with the mystery of its baleful eyes. And if ever, in a moment of distraction, he forgot the metaphysical horror of the world and those abysses at his feet, it was with a pang of remorse that he came again to himself, to the self of spiritual consciousness. He thought it right to be haunted, he refused to enjoy the pleasures of the created world, he liked walking among the gulfs. In his excess of conscious wisdom he was mad; for he sacrificed life to principles, to metaphysical abstractions, to the overmuch spirituality which is the negation of existence. He preferred death to life. Incomparably grosser and stupider than Pascal, almost immeasurably his inferiors, the men and women who move with shouting and laughter through the dusty heat of the fair are yet more wise than the philosopher. They are wise with the unconscious wisdom of the species, with the dumb, instinctive, physical wisdom of life itself. For it is life itself that, in the interests of living, commands them to be inconsistent. It is life itself that, having made them obscurely aware of Pascal's gulfs and horrors, bids them turn away from the baleful eyes of the Holy Face, bids them walk out of the dark, hushed, incense-smelling church into the sunlight, into the dust and whirling motion, the sweaty smell and the vast chaotic noise of the fair. It is life itself; and I, for one, have more confidence in the rightness of life than in that of any individual man, even if the man be Pascal.

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789 – 1869) was a German painter and a founder of the Nazarene art movement.

Film

<div style="padding:59.82% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1154456989?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Purple Noon clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Joseph Nguyen

1h 4m

1.14.26

In this clip, Rick speaks with Joseph Nguyen about turning fear into a tool for motivation.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/uemh44g4/widget?token=b741677e0f8eba9f87233f8dc8217d26" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1154454527?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Firing Line clip 10"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

AI, Bauhaus and the Case for Philosophical R&D

Molly Hankins January 13, 2026

As we begin our co-evolution with AI, questions are being raised from all sectors about the existential implications of this technological quantum leap.

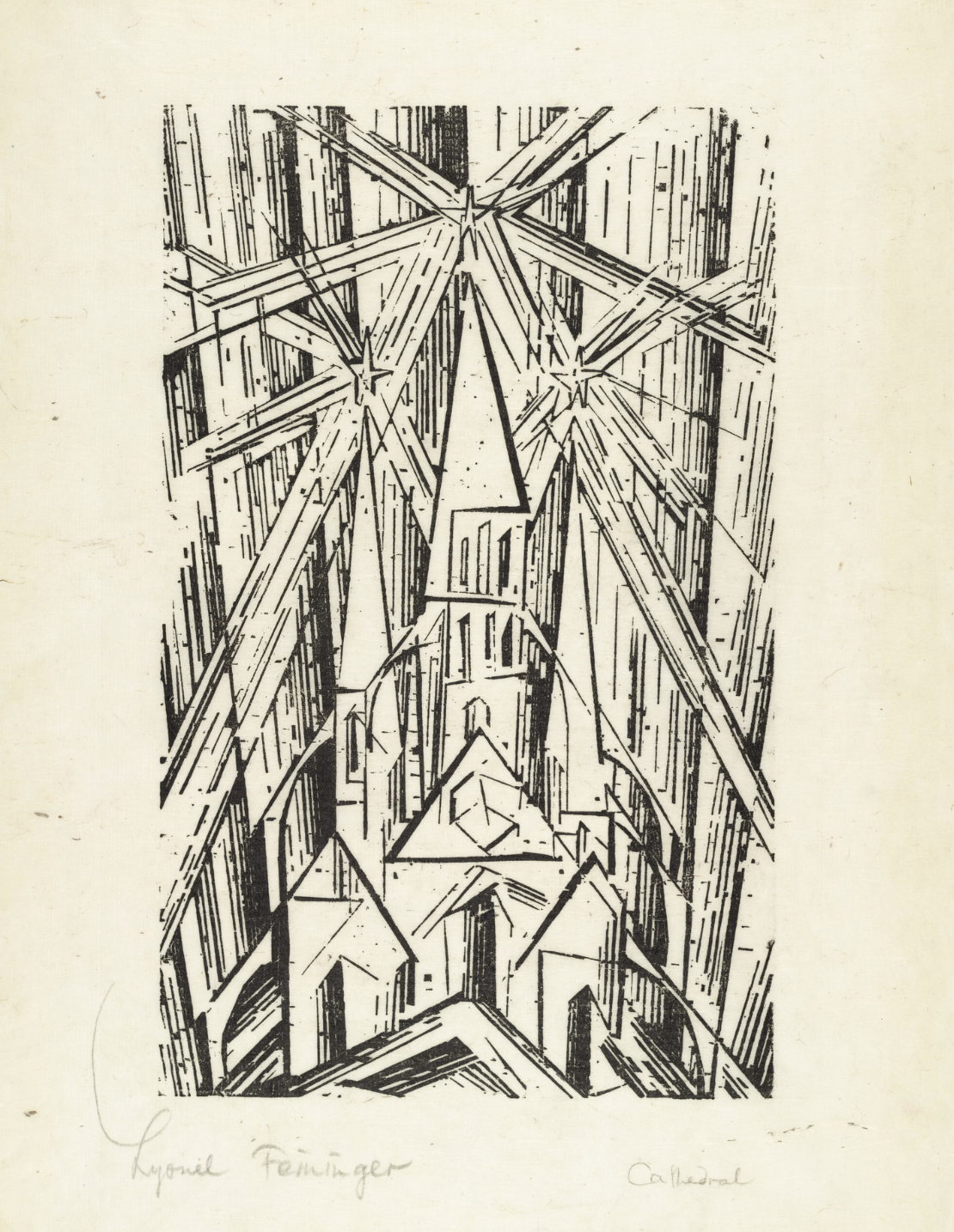

Cathedral (Kathedrale), Lyonel Feininger. 1919. Used as the cover for the Bauhaus Manifesto.

Molly Hankins January 13, 2026

As we begin our co-evolution with AI, questions are being raised from all sectors about the existential implications of this technological quantum leap. According to philosopher Tobias Rees, investment in philosophical AI R&D, and using the ideas generated to further long-term thinking when it comes to responsibleAI engagement practices, is absolutely essential. He believes the true danger of AI is the conceptual lag of humans more than the rapid progression of the tech. “I am adamant that those who build AI understand the philosophical stakes of AI,” Tobias said in an interview with Noema Magazine. “AI defies many of the most fundamental, most taken-for-granted concepts — or philosophies — that have defined the modern period and that most humans still mostly live by.” This millennium, technology has been evolving faster than our ability to learn how to responsibly use it, but the stakes have become much higher with the emergence of general intelligence.

Rees is not worried about AI being smarter than humans but he does believe it’s critical to study how to use it in complement with our human intelligence. “For example, AI has much more information available than we do and it can access and work through this information faster than we can. It also can discover logical structures in data —patterns — where we see nothing. Perhaps one must pause for a moment to recognize how extraordinary this is. AI can literally give us access to spaces that we, on our own, qua human, cannot discover and cannot access. How amazing is this?” Rees asks. The dimensions of life that open up by learning how to work with increasingly sophisticated AI are barely conceivable at this stage in our co-evolution, but awfully exciting to consider.

For instance, what would happen if we used AI to generate data about ourselves, in order to understand our patterns and how we can work on our personal development goals? Rees asks us to, "Imagine an on-device AI system — an AI model that exists only on your devices and is not connected to the internet — that has access to all your data. Your emails, your messages, your documents, your voice memos, your photos, your songs, etc. I stress on-device because it matters that no third parties have access to your data. Such an AI system can make me visible to myself in ways neither I nor any other human can. It literally can lift me above me. It can show me myself from outside of myself, show me the patterns of thoughts and behaviors that have come to define me.” These insights, if taken to heart and acted upon, could offer specific means for disrupting patterns that are often operating at an unconscious level.

“Bauhaus brought artists, engineers and designers together with the mission of elevating architecture to the 20th century and beyond. Now, 25 years into the 21st century, we are well into the most prolific technological advancement in human history, and most of us don’t even know what questions to ask about it.”

To understand why this kind of self-reflective partnership is even possible, we have to pause on what makes contemporary AI fundamentally different from earlier technology. For most of technological history, machines mirrored human logic in advance; we told them what to do and how to do it. Intelligence lived upstream in the designer’s assumptions, rules, and categories. The machine merely executed. What we are encountering now is something more strange and less predictable. “We do not give them their knowledge. We do not program them. Rather, they learn on their own, for themselves, and, based on what they have learned, they can navigate situations or answer questions they have never seen before. That is, they are no longer closed, deterministic systems. Instead they have a sort of openness and a sort of agentive behavior, a deliberation or decision-making space that no technical system before them ever had,” he explained.

Rees points to the Bauhaus School, founded in 1919 in Germany by architect Walter Gropius. He believed that the introduction of new building materials such as steel, concrete, and large-scale glass represented such a fundamental rupture to the field of architecture - which had been working with essentially the same building materials for centuries - that a multi-disciplinary educational think-tank was needed to understand how to best utilize them. Rees says, “We need philosophical R&D labs that would allow us to explore and practice AI as the experimental philosophy it is. Billions are being poured into many different aspects of AI but very little into the kind of philosophical work that can help us discover and invent new concepts — new vocabularies for being human — in the world today.” Bauhaus brought artists, engineers and designers together with the mission of elevating architecture to the 20th century and beyond. Now, 25 years into the 21st century, we are well into the most prolific technological advancement in human history, and most of us don’t even know what questions to ask about it.

AI ethics think tanks done Rees’s way, with a philosophical R&D approach and participating voices from many different disciplines, are how we prevent the future of AI from being determined solely by corporate incentives, security panic, or political agendas. If we don’t make the investment in understanding the nature of our relationship with AI, Rees predicts that people will keep trying to understand the new in terms of old paradigms, which won’t work, and we’ll get decades of turbulence as a result. Answering the question ‘how do we evolve the human concepts that will determine what AI becomes in the world?’ may spare us some of the growing pains of co-evolving with AI, particularly general artificial intelligence. Rees founded limn, a philosophical R&D lab, which has a YouTube full of elegantly simple explanations of this complex subject, and serves as an invitation to get us thinking about what’s to come with AI, and what kind of relationship we want to have with it.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1154446592?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Portrait of Jennie clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - April 4, 2025

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

10 Walking - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 10, 2026

Walking on a tiger's tail; it doesn’t bite…

Chris Gabriel January 10, 2026

Judgment

Walking on a tiger's tail; it doesn’t bite.

Lines

1

Walking on.

2

Walking the easy way on your own.

3

A blind man can see like a lame man can walk. Walking on a tiger’s tail and being bitten.

4

Walking on a tiger’s tail with a heart full of fear.

5

Walking the line.

6

Walking and watching your step. The time comes.

Qabalah

Kether to Binah: The Path of Beth. The Magician.

The Magician walks carefully along the path.

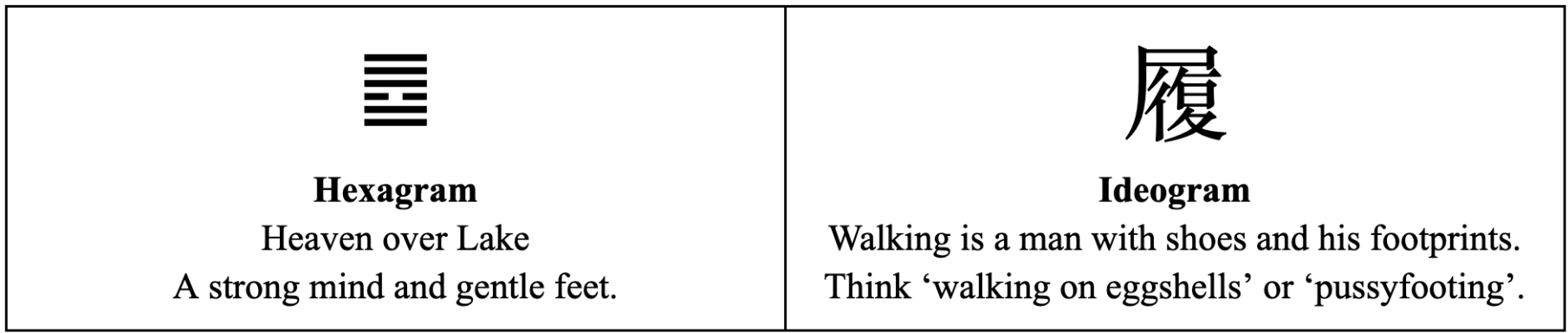

In this hexagram we see the image of caution, and of walking carefully. At times, we are confronted with dangers too great to oppose and must tread lightly. The image is pleasant, that of a calm lake under the heavens, but here we apply it to the body: the head is strong and driven, while the feet are soft and gentle.

The ideogram deepens the image, walking and watching your steps so as not to make a sound. The lines of writing show us the dynamics that form from this situation.

The Judgment gives us the danger - a tiger - we are behind it and walk over its tail, yet it doesn’t bite. When you walk gently enough, you can avoid the claws and fangs of the beast.

1

Sometimes the best thing to do is just keep walking.

2

If your path is certain and your eyes are open, trouble rarely comes. It is in erring from the path that we tend to walk into dangerous situations. Think of how walking along a main road differs from walking in a dark alley.

3

When we are distracted or uncertain, we invite trouble. One can picture a tourist in a crowded city, their uncertainty and awkwardness is immediately apparent to thieves. Or when we are walking while texting and nearly head into traffic.

4At times, fear is the proper reaction to danger. Without fear mankind would have died out long ago. This is the gift of our fight or flight response. There is no use fighting a tiger.

5

Walking the line is walking the “straight and narrow”. Take these verses from Matthew 7:13-14:

13 Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat:

14 Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

6

When we walk carefully through danger, we can often escape it entirely.

As this hexagram corresponds to the Magician, I think of the relation with Mercury, the God of Thieves, who shows how a thief who walks very carefully and quietly can achieve his ends. Or of the Magician himself, who carefully “walks the circle” and stays within it, lest he be torn asunder.

A more positive view of the dynamic here is that of gymnasts, skaters and mountain climbers, who do something very dangerous with astonishing grace and skill. With regard to “the straight and narrow” an acrobat can dance on a tightrope! It calls to mind a line from magician and mountaineer Aleister Crowley’s Book of Lies:

He leapt from rock to rock of the moraine without ever casting his eyes upon the ground.

Expertise is one form of magick, faith is another. The expert is beyond faith, their body and mind are attuned to the otherwise dangerous and difficult situations they find themselves in. Faith lets anyone walk without fear. Psalm 23 says it best:

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Therefore, let us learn what the Magician knows well: the art of walking and of faith, so no danger can assail us as we go through the world.

Numerology, Fibonacci, and Magic

Flora Knight January 8, 2026

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but to study them reveals the underlying principles that are deeply intertwined not just with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe, but with the mystical world in it’s totality…

Albrecht Durer, Melencolia I featuring a magic numerology square. (1514)

Flora Knight January 8, 2026

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but their underlying principles are deeply intertwined with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe. Two spiritual interpretations derived from the Fibonacci sequence are particularly noteworthy in our modern magical understandings, and particularly in the practice of Wicca: the concepts of twin flames and the number 33 sequence.

The spiral and golden rectangle of the Fibonacci sequence.

The idea of twin flames has long been embedded in magical traditions. Love, often symbolized by two flames, is a recurring theme in love spells and incantations, where lighting two candles side by side is believed to elevate love to a higher spiritual plane. This concept is represented by the number 11, a significant number in witchcraft. The Fibonacci sequence begins with 1 + 1, a numerical foundation that has been embraced by some modern Wicca sects as resonating with the essence of twin flames.

Another intriguing use of the Fibonacci sequence involves starting the sequence with the number 33. The number 3 represents the mind, body, and spirit, so 33 symbolizes the spiritual realization of these elements. When the Fibonacci sequence begins with 33, it leads to important numbers such as 3, 6, and 9, which are said to represent the ascension of the universe. Mapping these numbers on a grid also forms a pentagram, a powerful symbol in Wicca.

The 12th number in this modified Fibonacci sequence is 432, a number of profound significance in modern Wicca. The frequency of 432 Hz resonates with the universe’s golden mean, Phi, and harmonizes various aspects of existence including light, time, space, matter, gravity, magnetism, biology, DNA, and consciousness. When our atoms and DNA resonate with this natural spiral pattern, our connection to nature is enhanced.

The number 432 also appears in the ratios of the sun, Earth, and moon, as well as in the precession of the equinoxes, the Great Pyramid of Egypt, Stonehenge, and the Sri Yantra, among other sacred sites. While Fibonacci sequences were not commonly used in traditional magic before the 20th century, we see their presence everywhere, and they are meaningful in explanations of sacred geometry.

“This sequence, when viewed through a spiritual lens, reveals the underlying order and symmetry in nature, guiding us toward a deeper appreciation of the divine patterns that govern our existence.”

But beyond just Fibonacci, the study of numbers reveals secrets of the world, and to understand the magical perspective of the world, we must understand how different numbers carry various symbolic meanings:

William F. Warren, Illustration from Paradise Found. (1885).

1: The universe; the source of all.

2: The Goddess and God; perfect duality; balance.

3: The Triple Goddess; lunar phases; the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of humanity.

4: The elements; spirits of the stones; winds; seasons.

5: The senses; the pentagram; the elements plus Akasha; a Goddess number.

7: The planets known to the ancients; the lunar phase; power; protection and magic.

8: The number of Sabbats; a number of the God.

9: A number of the Goddess.

11: The twin flames; the number of ethereal love.

13: The number of Esbats; a fortunate number.

15: A number of good fortune.

21: The number of Sabbats and Esbats in the Pagan year; a number of the Goddess.

28: A number of the Moon; a number 101 representing fertility.

The planets are numbered as follows in Wiccan numerology:

3: Saturn

7: Venus

4: Jupiter

8: Mercury

5: Mars

9: Moon

6: Sun

Numerology has been a significant aspect of witchcraft for nearly 3,000 years, with most numbers being assigned specific meanings by various magical traditions. The most consistent sacred numbers, linked to sacred geometry, are 4, 7, and 3. These numbers represent the universe, the earthly body, and the seven steps of ascension, respectively.

The story of the Tower of Babel illustrates the ancient understanding of the universe through numbers. The tower's seven stages were each dedicated to a planet, with colors symbolizing their attributes. This concept was further refined by Pythagoras, who is said to have learned the mystical significance of numbers during his travels to Babylon.

The seven steps of the tower symbolize the stages of knowledge, from stones to fire, plants, animals, humans, the starry heavens, and finally, the angels. Ascending these steps represents the journey towards divine knowledge, culminating in the eighth degree, the threshold of God's heavenly dwelling.

The Tower of Babel.

The square, though divided into seven, was respected as a mystical symbol. This reconciled the ancient fourfold view of the world with the seven heavens of later times, illustrating the harmony between earthly and cosmic orders.

In contemporary Wicca and broader spiritual practices, the exploration of numerology and Fibonacci sequences opens new pathways to understanding the universe and our place within it. These numerical patterns and sequences are not just abstract concepts; they reflect the intricate designs of nature and the cosmos. By integrating Fibonacci sequences into spiritual practices, modern Wiccans and seekers of wisdom can tap into a profound sense of unity and harmony with the natural world.

The Fibonacci sequence, with its origins in simple arithmetic, evolves into a complex and beautiful representation of life's interconnectedness. This sequence, when viewed through a spiritual lens, reveals the underlying order and symmetry in nature, guiding us toward a deeper appreciation of the divine patterns that govern our existence.

As we continue to explore and embrace these ancient and modern numerological insights, we can uncover new layers of meaning and connection. The study of numbers in any form invites us to see the world not just as a series of random events, but as a harmonious and purposeful tapestry. This perspective encourages a more profound spiritual journey, where every number, pattern, and sequence becomes a gateway to greater wisdom and enlightenment.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1152668848?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Achooo Mr. Kerrooschev!"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Mike White

1h 22m

1.7.26

In this clip, Rick speaks with Mike White about defied expectations during the casting process.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/0etulxid/widget?token=4cd785943f5f08d1236513b475eb40e2" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:72.58% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1152023699?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Othello clip 3"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Three Ways of Art (1810)

Friedrich Overbeck January 6, 2026

Three roads traverse the Land of Art, and, though they differ from one another, each has its peculiar charm, and all eventually lead the tireless traveller to his destination, the Temple of Immortality…

Italia und Germania, Friedrich Overbeck. 1828.

At the turn of the 19th century, Neo-Classicism was at its zenith. Paintings and sculptures paid homage the newly re-discovered ancient worlds of Rome and Greece with a simple, symmetrical, and overtly moral style. At the Vienna Academy in 1809, a group of 6 artists rejected this new movement and, out of protest and belief, took up a monastic life in Rome to search for an art born out of ‘a pure heart’. This group became derisively known as the Nazarenes, and Friedrich Overbeck was one of their leaders. They found the Neoclassicist fascination with both the ancient and the modern to be paganistic and lacking in soul, so looked instead to the artists of the Middle ages and early Renaissance. They mimicked the lifestyles of these painters, valuing hard, honest work and austere, holy living in a rundown monastery. Overbeck acknowledges in his remarkable essay that he is striving for the very same goal as his contemporaries, and is generous in his acceptance that the way of the Nazarenes is not the only way to reach it. Yet his bias is clear, a middle way between the ancient and the new, the truthful and the beautiful, is the best journey.

Friedrich Overbeck January 6, 2026

Three roads traverse the Land of Art, and, though they differ from one another, each has its peculiar charm, and all eventually lead the tireless traveller to his destination, the Temple of Immortality. Which of these three a young artist should choose ought therefore to be determined by his personal inclination, guided and fortified by reflection.

The first is the straight and simple Road of Nature and Truth. An uncorrupted human being will find much to please his heart and satisfy his curiosity along this road. It will lead him, for better or for worse, through fair, productive country, with many a beautiful view to delight him, through he may occasionally have to put up with monotonous stretches of wasteland as well. But, above these, the horizon will usually be bright, and the sun of Truth will never set. Of the three roads, this is the most heavily travelled. Many Netherlanders have left their footprints on it, and we may follow the older ones among them with pleasure, observing the steadiness of their direction which proves that these travellers advanced imperturbably on their road: not one of these tracks stops short of the goal. - But the most recent footprints are another matter; most of them run in zig-zags to the right and the left, indicating that those who made them looked this way and that, undecided, wondering whether or not to turn back and take another road. Many of these tracks, in fact, disappear into the surrounding wastes and deserts, into impenetrable country. What the traveller on this road must chiefly guard against are the bogs along one side where he may easily sink into mud over his ears, and the sandy wastes on the other side which may lead him away from the road and from his destination. But if he manages to continue along the straight, marked path, he cannot fail to reach his destination. The level country makes this road agreeable to travel, there are no mountains to climb, and the walking is easy, so long as he does not stray to one side or the other, into bog or desert. Besides, there is plenty of company to be found on this road, friendly people, representing all nationalities. And the sky above this country is usually serene. The careful observer will find here everything the earth offers, he need never be bored on this road. And yet, I must warn the young artist not to raise his expectation too high, for, frankly, he will see neither more, nor less than what other people also see, every day, in every lane.

The second road is the Road of Fantasy which leads through a country of fable and dream. It is the exact opposite of the first. On it, one cannot walk more than a hundred steps on level ground. It goes up and down, across terrifying cliffs and along steep chasms. The wanderer must often dare to take frightening leaps across the bottomless abyss. If he does not have the nerve for it, he will become dizzy at the first step. Only men of very strong constitution can take this road and follow it to the end. - Strange are its environs, usually steeped in night; only sudden lightning flashes intermittently illuminate the terrible, looming cliffs. The road often leads straight to a rock face and enters into a dark crevice, alive with strange creatures. Suddenly, a ray of light pierces the darkness from afar, the light increases as one follows it through the narrow crevice, until abruptly the rocks rccede and the brightness of a thousand suns envelops the traveller. Then he is seized, as if by heavenly powers, he eagerly plunges into the bright sea of joy, drinking its luminous waters with wild desire, then, intoxicated and full of fresh ardor, he tears himself from the depths and soars upward like an eagle, his eyes on the sun, until he vanishes from sight. Thus joy and terror succeed each other in sharpest contrast. Not the faintest glimmer of the light of Truth penetrates into these chasms, insurmountable mountains enclose the land, and only rarely do fleeting shadows or dream visions which can bear the light of Truth venture to drift across the barriers, where they then seem to stride like giants from peak to peak.

“Thus sunrise and sunset, Truth and Beauty alternate here, and combine, and from their union rises the ideal.”

Just as this land is the opposite of the land of Nature in every feature, it is its opposite also with respect to population. In the other land, the road is constantly thronged with travellers; here it is usually empty. Few dare to enter this region, and even these few have little in common with one another, they go their separate ways, each sufficient to himself, none paying attention to the others. Michelangelo's luminous trace shines above all in this darkness. What distinguishes this road from the other is the colossal and sublime. Never is anything common or ordinary seen here, everything is rare, new, unique. Never is the wanderer's mind at peace: wild joy and terror, fear and expectation beset him in turn.

Let those who love strong emotion and lawless freedom travel this road, and let them walk boldly, it is sure to take them most directly to their destination. But those who love gentler impressions, who can neither grasp the colossal, nor bear the humdrum, and who like neither the bright midday light of the land of Nature, nor the stormy night of the land of Fantasy, but would prefer to walk in the gentle twilight, my advice to them is to take the third road which lies midways between the other two: the Road of the Ideal or of Beauty. Here he will find a paradise spread before him where the flower-fragrance of spring combines with autumn's fruitfulness. - To his right rise the mountains of Fantasy, to his left the view sweeps across fertile vineyards to the beautiful plain of the Land of Nature. From this side, the setting sun of Truth sheds its light; from the other, the morning light of Beauty rises from behind the golden mountains of Fantasy and bathes the entire countryside in its rosy haze. Thus sunrise and sunset, Truth and Beauty alternate here, and combine, and from their union rises the ideal. Here even Fantasy appears in the light of Truth, and naked Truth is clothed in the rose-fragrance of Beauty.

This road, besides, is neither so populous as the first, nor so deserted as the second, and the travellers on it differ from those of the second road by their sociability. One sees them walking in pairs, and friendship and love, their constant companions and guides, strew flowers on their way. Then, too, this road is neither so definitely marked as the first, nor so unkempt as the second. It runs, in beautiful variety of setting, from hill to meadow, from lake shore to orange grove. Every imaginable loveliness contributes to this variety. But in the very charm of this road there lies a danger to the traveller, for it may cause him to forget his destination, and cause him to lose all desire for the Temple of Immortality. Thus it happens that some of the travellers are overtaken by death before they reach the Temple. A loving companion may then carry their body to the Temple's threshold, where it will at once return to life and everlasting youth.

These then, dear brothers in art, are the three roads; choose between them according to your inclination, but test your powers first, by using reason. Whichever road you choose, I should advise you to go forward on it without looking too much to the left or right. The proof that each of the three roads leads to the goal is given three men who went separate ways and whose names are equally respected by posterity: Michelangelo took the road of Fantasy, Raphael the road of Beauty, and Dürer that of Nature, though he not infrequently crossed over into the land by Beauty.

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789 – 1869) was a German painter and a founder of the Nazarene art movement.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1152020135?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Alabama Highlands (1937)"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - December 15, 2025

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

9 The Small (Nurturing) - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 3, 2026

Dark clouds, but no rain in the Western Lands…

Chris Gabriel January 3, 2026

Judgment

Dark clouds, but no rain in the Western Lands.

Lines

1

Go your own way, what could go wrong?

2

Lead the way back.

3

A noisy ride where husband and wife can’t see eye to eye.

4

Have faith and the fear of blood goes.

5

With entwined faith we are rich in neighbors

6

The rain came down. Still virtue grew. A woman in danger, the Moon is almost full. The Sage’s journey will be unfortunate.

Qabalah

Chokmah, the Paternal. The 4 Twos. The 2 of Swords and the 2 of Disks.

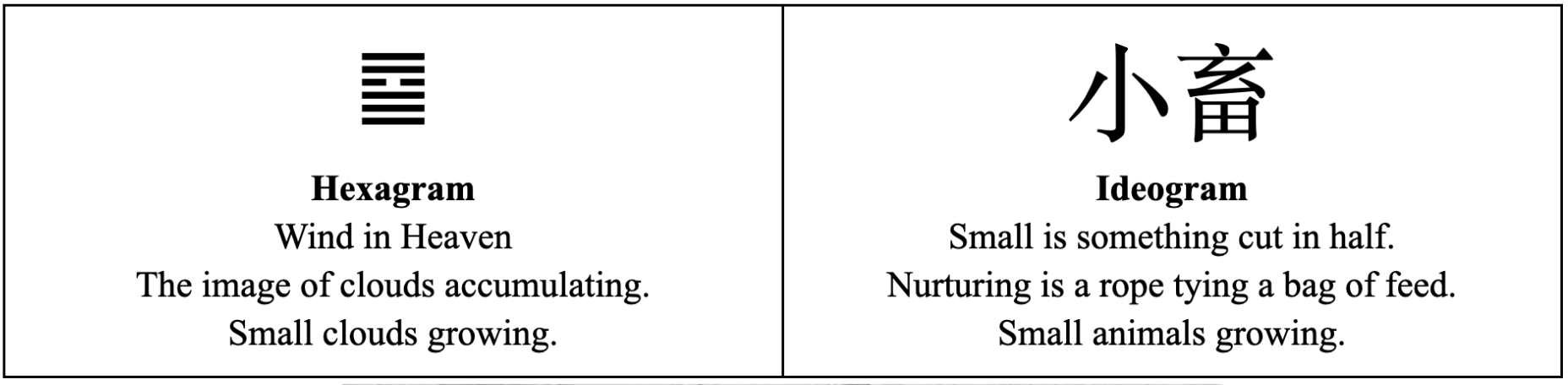

In hexagram 9, we are given the image of accumulation: the process of making a mountain out of a molehill, of turning something little into something big. This can be the growth of a great storm cloud from a small bit of moisture, or the growth of a baby into an adult. This can be applied to social dynamics too, as written in the lines. It is also the phenomena of perspective and proportion, how something large and distant looks small. Thus the hexagram is a cloud far up in the heavens, looking very small from the ground.

We are shown dark clouds that bring no rain, for they are still growing.

1

One must follow their own path to grow. Each vine, flower, and tree fights for its own sunlight, and contorts itself to do so. They follow their own way to survive.

2

At times, growth requires retreat, though it may appear as regression. No matter how far one goes, we still need to sleep.

3

This is the social form of making a mountain out of a molehill. If a couple is driving and they get a flat tire, it can elicit an argument fantastically out of proportion to the minor inconvenience they’ve experienced. The little problem grows into a drama representing the problems of the whole relationship.

4

When we have faith in the ultimate goal of growth, our anxieties fade and the hard work necessary to achieve such a thing becomes light.

5

When we show a little kindness and goodwill to those around us, we will often find they are willing to support us in times of need. Bringing flowers or gifts to a new neighbor can invite a friendship and reciprocal kindness.

6

When things have grown, we see their fruits. When things reach their fullness, so too does the danger of spilling. A cloud which accumulates enough water soon bursts forth and pours out the rain it has accumulated.

Nietzsche expresses this dynamic well in Zarathustra:

“Indeed, who was not defeated in his victory!

Indeed, whose eye did not darken in this drunken twilight!

Indeed, whose foot did not stagger and forget how to stand in victory!

– That I may one day be ready and ripe in the great noon; ready and ripe

like glowing bronze, clouds pregnant with lightning and swelling udders of milk –”

As we grow, things become more treacherous and the stakes become higher. At the final moment, we can slip, and spill all that we’ve made. Consider children playing with blocks or sandcastles, or building a house of cards; we can keep these things steady as we build them up, but as we prepare to finish them, it can all come tumbling down. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra prays to his Will that he will be able to maintain this state of growth and height, that his accumulated energy can be directed properly at the right time, not lost in pride.

Pride comes before a Fall.