Helene’s Florist

RICHARD ESTES

Perfectly empty, eerily perfect - Estes’ worlds are devoid of people and rendered in such remarkable detail as to almost appear as photographs. Yet it is their perfection that belies their truth, for no camera at the time would have been able to capture such even focus across such a vast depth of field as Estes could do with oil and a brush. His works are uncanny and uncomfortable, the abandoned spaces give us nothing to grab onto. He paints the visual complexity of urban life and reveals it for its difficulties by removing the human, leaving us only able to stare in aesthetic appreciation or horror at the world we inhabit. In this way, Este asks us to slow down with his work, to show that all around us there is room for visual appreciation for those with the eyes to see. To see through the noise of city life, details begin to emerge everywhere - the beauty of typography on a sign, the arrangement of flowers and paving stones, the subtle architecture of storefronts. In Estes’ hands, the mundane comes to life on the page and in the viewers mind.

Richard Estes

RICHARD ESTE, 1932. OIL ON CANVAS.

Perfectly empty, eerily perfect - Estes’ worlds are devoid of people and rendered in such remarkable detail as to almost appear as photographs. Yet it is their perfection that belies their truth, for no camera at the time would have been able to capture such even focus across such a vast depth of field as Estes could do with oil and a brush. His works are uncanny and uncomfortable, the abandoned spaces give us nothing to grab onto. He paints the visual complexity of urban life and reveals it for its difficulties by removing the human, leaving us only able to stare in aesthetic appreciation or horror at the world we inhabit. In this way, Este asks us to slow down with his work, to show that all around us there is room for visual appreciation for those with the eyes to see. To see through the noise of city life, details begin to emerge everywhere - the beauty of typography on a sign, the arrangement of flowers and paving stones, the subtle architecture of storefronts. In Este’s hands, the mundane comes to life on the page and in the viewers mind.

Summer #2

ADOLF GOTTLIEB

A floating orb glows with searing intensity. It is the summer sun that brings with it joys and dangers in equal measure, that enforces a regularity and order to life dictated by its rising and falling. Below, a violent, calligraphic, abstract form grounds us in entropy, chaos, and the fallibility of humans. “I feel that I use color in terms of an emotional quality... a vehicle for the expression of feeling.”, said Gottlieb, “Now what this feeling is, is something I probably can't define, but since I eliminated almost everything from my painting except a few colors and perhaps two or three shapes, I feel a necessity for making the particular colors that I use, or the particular shapes, carry the burden of everything that I want to express, and all has to be concentrated within these few elements. Therefore, the color has to carry the burden of this effort”. And carry the burden, his colors do: soft pink hues, electric scarlet, dark blood reds, and the brown of earth speak to apocalypse as much as to connection and human flesh. Gottlieb represents summer as something that engulfs us, that we long for and fear, and mustn’t look at too long in case it damages our eyes.

Adolf Gottlieb

ADOLF GOTTLIEB, 1964. OIL ON LINEN.

A floating orb glows with searing intensity. It is the summer sun that brings with it joys and dangers in equal measure, that enforces a regularity and order to life dictated by its rising and falling. Below, a violent, calligraphic, abstract form grounds us in entropy, chaos, and the fallibility of humans. “I feel that I use color in terms of an emotional quality... a vehicle for the expression of feeling.”, said Gottlieb, “Now what this feeling is, is something I probably can't define, but since I eliminated almost everything from my painting except a few colors and perhaps two or three shapes, I feel a necessity for making the particular colors that I use, or the particular shapes, carry the burden of everything that I want to express, and all has to be concentrated within these few elements. Therefore, the color has to carry the burden of this effort”. And carry the burden, his colors do: soft pink hues, electric scarlet, dark blood reds, and the brown of earth speak to apocalypse as much as to connection and human flesh. Gottlieb represents summer as something that engulfs us, that we long for and fear, and mustn’t look at too long in case it damages our eyes.

Agony in the Garden

EL GRECO

As the Last Supper finished, Jesus retreated to the Garden of Gethsemane. He brought with him Peter, John, and James, and asked them to stay awake and pray, while he went further ahead, alone and began to ask his father for salvation. "My Father,”, he said, “if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Nevertheless, let it be as You, not I, would have it. If this cup cannot pass by, but I must drink it, Your will be done!” Knowing his fate, that he was destined for the cross, and the agony of death, his humanness shows. He fears what is ahead of him, and bargains one last time for a world in which his fated end may be escaped. Yet, despite it all, he is adamant that if this really is what is required, he will do it willingly. Leaving the garden, he finds the three apostles who had accompanied him fast asleep, and declares them strong in spirit but weak in flesh. One of the most important stories in the Passion of Jesus, El Greco renders this moment in perfect duality. Christ exists in the centre, flanked by humanity and divinity, caught between worlds with dignity and fear.

El Greco

EL GRECO, 1590. OIL ON CANVAS.

As the Last Supper finished, Jesus retreated to the Garden of Gethsemane. He brought with him Peter, John, and James, and asked them to stay awake and pray, while he went further ahead, alone and began to ask his father for salvation. "My Father,”, he said, “if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Nevertheless, let it be as You, not I, would have it. If this cup cannot pass by, but I must drink it, Your will be done!” Knowing his fate, that he was destined for the cross, and the agony of death, his humanness shows. He fears what is ahead of him, and bargains one last time for a world in which his fated end may be escaped. Yet, despite it all, he is adamant that if this really is what is required, he will do it willingly. Leaving the garden, he finds the three apostles who had accompanied him fast asleep, and declares them strong in spirit but weak in flesh. One of the most important stories in the Passion of Jesus, El Greco renders this moment in perfect duality. Christ exists in the centre, flanked by humanity and divinity, caught between worlds with dignity and fear.

Antibes Seen from La Salis

CLAUDE MONET

Even the great master of Impressionism himself, who had taught the world how to capture nature, light, color, and form in all of its beauty and translate the splendour of the environment into oil and canvas, felt humbled by the view ahead of him. Spending the summer in France’s southern coast in the old town of Antibes, Claude Monet would walk the landscapes along the Azure Coast with his easel and canvas, setting up to paint en plein air, wherever the beauty struck him. Yet, unusually, he laboured over the works here. The sun, the trees, the sea, all were, as he wrote in letters to friends and contemporaries, almost too beautiful to bear - ‘In order to paint here one would need gold and precious stones’, he wrote to the sculptor Auguste Rodin. He saw Antibes as a fairy-tale town, one that existed as much in the imagination as it did in reality, and so his usually deftness of capturing the impression, the feeling of a moment was further out of reach. Yet his work here is some of the most delicate and beautiful of his career, the dazzling sweetness of the landscape is abundant and intoxicating.

Claude Monet

CLAUDE MONET, 1888. OIL ON CANVAS.

Even the great master of Impressionism himself, who had taught the world how to capture nature, light, color, and form in all of its beauty and translate the splendour of the environment into oil and canvas, felt humbled by the view ahead of him. Spending the summer in France’s southern coast in the old town of Antibes, Claude Monet would walk the landscapes along the Azure Coast with his easel and canvas, setting up to paint en plein air, wherever the beauty struck him. Yet, unusually, he laboured over the works here. The sun, the trees, the sea, all were, as he wrote in letters to friends and contemporaries, almost too beautiful to bear - ‘In order to paint here one would need gold and precious stones’, he wrote to the sculptor Auguste Rodin. He saw Antibes as a fairy-tale town, one that existed as much in the imagination as it did in reality, and so his usually deftness of capturing the impression, the feeling of a moment was further out of reach. Yet his work here is some of the most delicate and beautiful of his career, the dazzling sweetness of the landscape is abundant and intoxicating.

Blue Jay

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

“A line is a line, but is [also] a color. It does this here, but that there. The canvas surface is flat and yet the space extends for miles.” This is at the very heart of Helen Frankenthaler’s work. In every corner of the canvas, there is the opportunity for change, for deception, and for interpretation. Developing a technique known as ‘soak-staining’, whereby she loosed oil paint and allowed the natural flow of a viscous matter to guide the formal shapes of the work, Frankenthaler’s process was open to the chaos of the world. Oil paints take on the quality of watercolour, and what would once be considered mistakes become acts of deep intention. For all of its aesthetic beauty and apparent simplicity, in her hand the artwork becomes a vehicle for painterly deception. Perhaps, then, Frankenthaler is simply making explicit that which we have always known about painting; that we are willing tricked in each instance we engage with it.

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN FRANKENTHALER, 1963. OIL ON CANVAS.

“A line is a line, but is [also] a color. It does this here, but that there. The canvas surface is flat and yet the space extends for miles.” This is at the very heart of Helen Frankenthaler’s work. In every corner of the canvas, there is the opportunity for change, for deception, and for interpretation. Developing a technique known as ‘soak-staining’, whereby she loosed oil paint and allowed the natural flow of a viscous matter to guide the formal shapes of the work, Frankenthaler’s process was open to the chaos of the world. Oil paints take on the quality of watercolour, and what would once be considered mistakes become acts of deep intention. For all of its aesthetic beauty and apparent simplicity, in her hand the artwork becomes a vehicle for painterly deception. Perhaps, then, Frankenthaler is simply making explicit that which we have always known about painting; that we are willing tricked in each instance we engage with it.

Lac Laronge IV

FRANK STELLA

Restless forms are constrained by their canvas. Arcs and circles push against their geometric home, straining their boundaries and compressing against the confinement of the rectangle. Stella had, in the period before this series of works was executed, been using canvases of irregular shapes, defined by the forms of the painting themselves. The same ideas are at play here, namely those of the relationship between the surface and the image upon it, but the surface now takes precedence. Stella’s forms, made by a protractor and paint, seem to fight against each other for prominence; as you stare into the flat expanse of the image the colors dance between the foreground and background. Despite it’s pleasing, almost gentle appearance, there is a fight happening in every aspect of the painting, a battle for visual priority between forms and right of space between surface and image. The painting, in this way, transcends its abstract forms to become something tangibly real - Stella imbues visual forms with a life-force quite unlike any other.

Frank Stella

FRANK STELLA, 1969. ACRYLIC POLYMER ON CANVAS.

Restless forms are constrained by their canvas. Arcs and circles push against their geometric home, straining their boundaries and compressing against the confinement of the rectangle. Stella had, in the period before this series of works was executed, been using canvases of irregular shapes, defined by the forms of the painting themselves. The same ideas are at play here, namely those of the relationship between the surface and the image upon it, but the surface now takes precedence. Stella’s forms, made by a protractor and paint, seem to fight against each other for prominence; as you stare into the flat expanse of the image the colors dance between the foreground and background. Despite it’s pleasing, almost gentle appearance, there is a fight happening in every aspect of the painting, a battle for visual priority between forms and right of space between surface and image. The painting, in this way, transcends its abstract forms to become something tangibly real - Stella imbues visual forms with a life-force quite unlike any other.

Reclining Woman

FERNAND LÉGER

Cubism, war, and industrialism - these were the three muses of Léger’s career in the early 1920s. One of the first artists to join Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s new movement of Cubism, he exhibited in all of the early shows and helped define the new art language to the public. While his contemporaries cubist forms were rigid and angular, Léger’s style came to be known as “Tubism”, so named for the tubular, pipe like mechanical structures that served as the subjects or motifs for so much of his early work. Yet experiences fighting at the front in World War I softened his allegiances to industrial forms, and by 1922 he had swapped metal for flesh, and abstracted still lives had been replaced by figurative forms, still retaining his ‘Tubist’ influences. Léger felt that art was more important than ever in the post-war period, and that the work he had been doing before the war was academic, restrictive and inaccessible to most save for the privileged, educated few. His movement toward portraiture and nudes was an attempt to show the poetry of the everyday experience, to take images and scenes familiar to the masses and elevate them into something unusual, thought-provoking and beautiful.

Fernand Léger

FERNAND LÉGER, 1922. OIL ON CANVAS.

Cubism, war, and industrialism - these were the three muses of Léger’s career in the early 1920s. One of the first artists to join Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s new movement of Cubism, he exhibited in all of the early shows and helped define the new art language to the public. While his contemporaries cubist forms were rigid and angular, Léger’s style came to be known as “Tubism”, so named for the tubular, pipe like mechanical structures that served as the subjects or motifs for so much of his early work. Yet experiences fighting at the front in World War I softened his allegiances to industrial forms, and by 1922 he had swapped metal for flesh, and abstracted still lives had been replaced by figurative forms, still retaining his ‘Tubist’ influences. Léger felt that art was more important than ever in the post-war period, and that the work he had been doing before the war was academic, restrictive and inaccessible to most save for the privileged, educated few. His movement toward portraiture and nudes was an attempt to show the poetry of the everyday experience, to take images and scenes familiar to the masses and elevate them into something unusual, thought-provoking and beautiful.

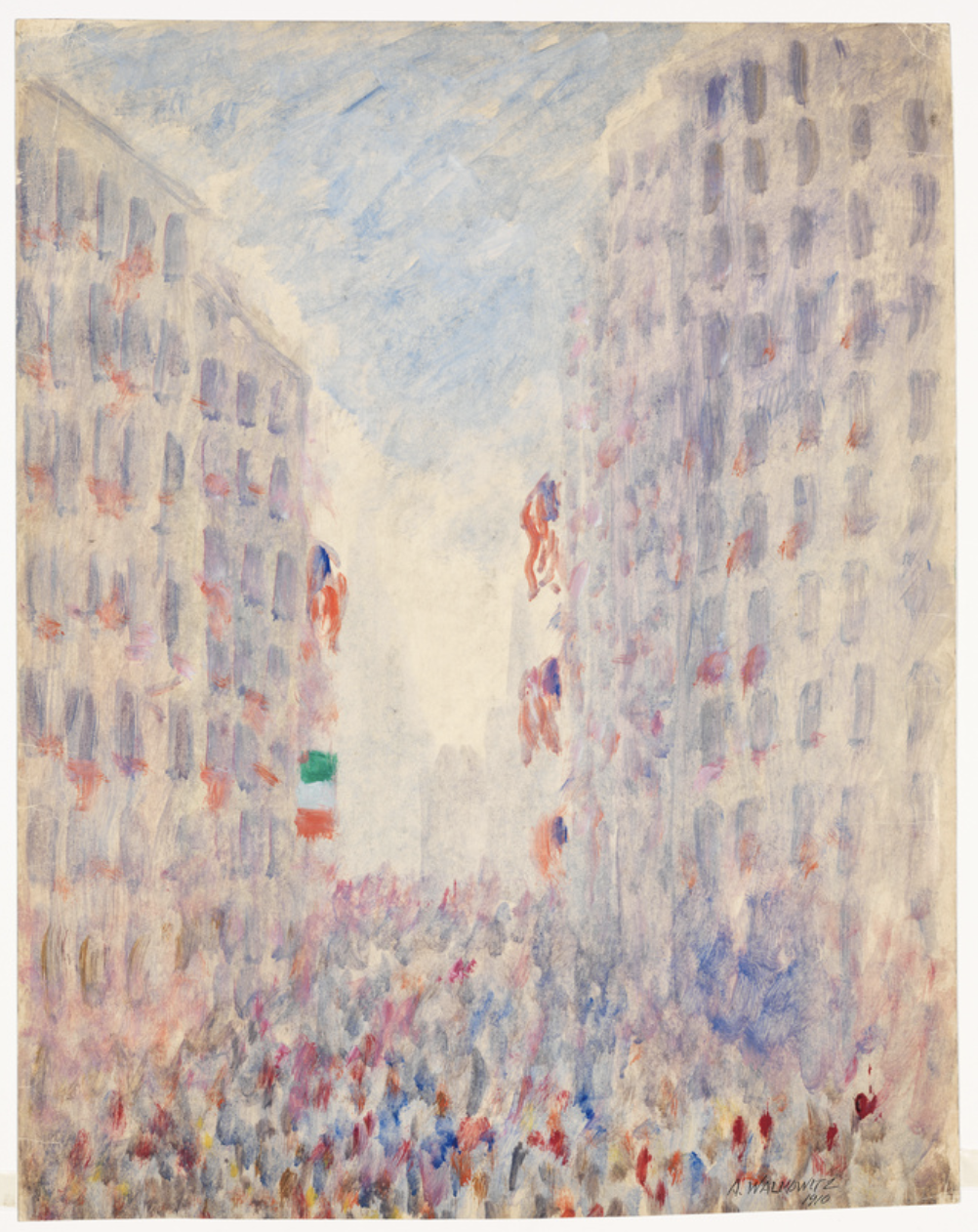

Parade

ABRAHAM WALKOWITZ

The intensity of simple, human experiences - this is what Abraham Walkowitz strove for in his work. Part of the first wave of American Moderists who brought the European ideals and philosophies to the United States, Walkowtiz interpreted these ideas in a uniquely American way. Where the European leading figures, such as Kandinsky, Klee, and Braque, were pushing the boundaries of thought and making art that was intentionally intellectual, laden with concepts as much as beauty that challenged and inspired, Walkowtiz digested these same progressions but approached them with what the artist and critic Oscar Bluemner called ‘an inner necessity.’ This is clear in his parade scene. The work is a masterful display of early abstraction, loose, sparing brushstrokes and vivid, varied colours give the suggestion of a scene without rigid focus of detail. Yet, for all the revolution in the technique and composition, the work is brimming with life and with joy. The essence of the parade is captured, the excitement of the human experience bounds across the paper. The viewer does not need education or information to understand the heart of Walkowtiz’s work, it exists for all to see.

Abraham Walkowitz

ABRAHAM WALKOWITZ, 1910. OIL ON PAPER.

The intensity of simple, human experiences - this is what Abraham Walkowitz strove for in his work. Part of the first wave of American Moderists who brought the European ideals and philosophies to the United States, Walkowtiz interpreted these ideas in a uniquely American way. Where the European leading figures, such as Kandinsky, Klee, and Braque, were pushing the boundaries of thought and making art that was intentionally intellectual, laden with concepts as much as beauty that challenged and inspired, Walkowtiz digested these same progressions but approached them with what the artist and critic Oscar Bluemner called ‘an inner necessity.’ This is clear in his parade scene. The work is a masterful display of early abstraction, loose, sparing brushstrokes and vivid, varied colours give the suggestion of a scene without rigid focus of detail. Yet, for all the revolution in the technique and composition, the work is brimming with life and with joy. The essence of the parade is captured, the excitement of the human experience bounds across the paper. The viewer does not need education or information to understand the heart of Walkowtiz’s work, it exists for all to see.

The Postman

VINCENT VAN GOGH

A chance meeting in a train station cafe led to the most fruitful sitter relationship of Van Gogh’s career. Joseph-Éttiene Roulin was the post master at the Arles train station, and a heavy drinker in the neighbouring bar. He was, by all accounts, a kindly man, towering in stature with a long beard and a soft, ‘socratic face’, according to Van Gogh. The two men became drinking buddies, and then as Van Gogh fell into his most severe depressive episode, leading to the mutilation of his ear, Roulin became his carer and a big brother figure to the struggling artist. It was Roulin, in fact, who cleaned the Yellow House of the blood, who brought Van Gogh to hospital, visited him in his months long stay in the asylum, and updated his brother Theo about Vincent’s state. Van Gogh felt indebted to Roulin, and over a six month period he painted six portraits of the postman, and 17 of his family, including his wife and all of his children. No other subject besides Van Gogh himself was depicted so frequently by his brush, and he brings a nobility to his humble friend, painting him against an ornate background that speaks to the portraiture of royalty.

Vincent Van Gogh

VINCENT VAN GOGH, 1889. OIL ON CANVAS.

A chance meeting in a train station cafe led to the most fruitful sitter relationship of Van Gogh’s career. Joseph-Éttiene Roulin was the post master at the Arles train station, and a heavy drinker in the neighbouring bar. He was, by all accounts, a kindly man, towering in stature with a long beard and a soft, ‘socratic face’, according to Van Gogh. The two men became drinking buddies, and then as Van Gogh fell into his most severe depressive episode, leading to the mutilation of his ear, Roulin became his carer and a big brother figure to the struggling artist. It was Roulin, in fact, who cleaned the Yellow House of the blood, who brought Van Gogh to hospital, visited him in his months long stay in the asylum, and updated his brother Theo about Vincent’s state. Van Gogh felt indebted to Roulin, and over a six month period he painted six portraits of the postman, and 17 of his family, including his wife and all of his children. No other subject besides Van Gogh himself was depicted so frequently by his brush, and he brings a nobility to his humble friend, painting him against an ornate background that speaks to the portraiture of royalty.

Christ in the Sepulchre, Guarded by Angels

BLAKE

William Blake was steeped in the Bible. A deeply spiritual man who rejected organised religion, he found endless inspiration in the Testaments contained within and understood them as works to be interpreted -“Both read the Bible day and night”, he wrote, “But thou readst black where I read white”. It was not, for him, a prescriptive book but an inspiring one, the stories told were not historical fact or laws for life, but ways to understand oneself and the world around them. In every medium Blake worked in, from poetry and scholarship to watercolour and sculpture, the Bible played a part in his process and creation. The work here was commissioned as part of an enormous series depicting 80 subjects from the Bible. ‘The Whole Bible is filld with Imaginations & Visions from End to End”, he said, “And not with Moral virtues that is the baseness of Plato & the Greeks & all Warriors. The Moral Virtues are continual Accusers of Sin & promote Eternal Wars & Domineering over others”.

William Blake

WILLIAM BLAKE, 1805. WATERCOLOR ON PAPER.

William Blake was steeped in the Bible. A deeply spiritual man who rejected organised religion, he found endless inspiration in the Testaments contained within and understood them as works to be interpreted -“Both read the Bible day and night”, he wrote, “But thou readst black where I read white”. It was not, for him, a prescriptive book but an inspiring one, the stories told were not historical fact or laws for life, but ways to understand oneself and the world around them. In every medium Blake worked in, from poetry and scholarship to watercolour and sculpture, the Bible played a part in his process and creation. The work here was commissioned as part of an enormous series depicting 80 subjects from the Bible. ‘The Whole Bible is filld with Imaginations & Visions from End to End”, he said, “And not with Moral virtues that is the baseness of Plato & the Greeks & all Warriors. The Moral Virtues are continual Accusers of Sin & promote Eternal Wars & Domineering over others”.

Madame Monet Embroidering

CLAUDE MONET

For a brief moment, the beauty of domesticity was greater than that of nature. Monet mostly painted outside, bringing his canvas out for long days in the fresh air, working en plein air to capture waterlilies, sunsets, rivers, and fields. The great father of modernism, and the creator of the painting for which Impressionism took its name, wanted to capture the world not as it necessarily was, but as he saw it. Here, however, he brought his easel and brushes inside, and painted this delicate, beautiful work of his wife quietly absorbed in her embroidery loom. Light remains a focus, it ebbs through the large windows and dances off her dress and her face. There is such tenderness in every brush stroke, the whole painting seems to exude a powerful, understated romance. It is not wild with passion or energy, nor is it attempting at objectivity. Instead it is a quiet ode to love and marriage, and to the beauty of co-habitation as Monet saw it.

Claude Monet

CLAUDE MONET, 1875. OIL ON CANVAS.

For a brief moment, the beauty of domesticity was greater than that of nature. Monet mostly painted outside, bringing his canvas out for long days in the fresh air, working en plein air to capture waterlilies, sunsets, rivers, and fields. The great father of modernism, and the creator of the painting for which Impressionism took its name, wanted to capture the world not as it necessarily was, but as he saw it. Here, however, he brought his easel and brushes inside, and painted this delicate, beautiful work of his wife quietly absorbed in her embroidery loom. Light remains a focus, it ebbs through the large windows and dances off her dress and her face. There is such tenderness in every brush stroke, the whole painting seems to exude a powerful, understated romance. It is not wild with passion or energy, nor is it attempting at objectivity. Instead it is a quiet ode to love and marriage, and to the beauty of co-habitation as Monet saw it.

Paris Abstraction

ISAMU NOGUCHI

Born in Los Angeles to a Japanese poet father and am American writer mother, by the age of 24 Isamu Noguchi had lived many lives across multiple continents and found himself apprenticing for the great sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi in Paris. The two could hardly communicate - Noguchi spoke almost no French and Brâncuşi little English - but for two years he learnt from this master of modernism not just how to render wood, stone, and steel, but how to appreciate the ‘value of a moment’. Noguchi would go on to become one of the most significant sculptors and furniture designers of the 20th century, combining a Japanese design aesthetic with a western modernist philosophy, but in the summer of 1927, the young man was learning how to reduce the world to it’s most elegant, pure, and beautiful forms. Brâncuşi’s mastery was in finding the platonic ideal of a given subject, discovering the fewest elements that could be combined to create a truthful likeness and it was this quality that Noguchi was learning from. His drawing here, a medium he felt he lost mastery of as he aged, shows both the influence of his teacher and omens of his career to come.

Isamu Noguchi

ISAMU NOGUCHI, c.1927. WATERCOLOUR, INK, AND GRAPHIC ON PAPER.

Born in Los Angeles to a Japanese poet father and am American writer mother, by the age of 24 Isamu Noguchi had lived many lives across multiple continents and found himself apprenticing for the great sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi in Paris. The two could hardly communicate - Noguchi spoke almost no French and Brâncuşi little English - but for two years he learnt from this master of modernism not just how to render wood, stone, and steel, but how to appreciate the ‘value of a moment’. Noguchi would go on to become one of the most significant sculptors and furniture designers of the 20th century, combining a Japanese design aesthetic with a western modernist philosophy, but in the summer of 1927, the young man was learning how to reduce the world to it’s most elegant, pure, and beautiful forms. Brâncuşi’s mastery was in finding the platonic ideal of a given subject, discovering the fewest elements that could be combined to create a truthful likeness and it was this quality that Noguchi was learning from. His drawing here, a medium he felt he lost mastery of as he aged, shows both the influence of his teacher and omens of his career to come.

Keepsake from Corsica

DORA BOTHWELL

A deep, lifelong passion for travel defined Dora Bothwell’s life, far more than her art or relationships. A native San Franciscan, she trained as a dancer while a teenager but, following the death of her father in her early 20s, she used a small inheritance to travel to Samoa where she was adopted by a village chief and his family. There, she learn the Samoan language, dance practices, traditional ceremonies and the artistry of the local textile designers and manufactures. For the two years she spent in Samoa, she developed a visual language and art practice that would stay with her for the rest of her life. Incorporating rigorous training and European avant-garde influences, she made work that spoke to the place she was in with insight and reverence but remained recognisably hers. Her art, then, serves as a kind of scrapbook of her travels, a visual record of the way that movement changed, informed, and inspired her. This ‘Keepsake from Corsica’ immediately conjures blue seas and iridescent shells, and the dance of sunlight as it dapples across the land.

Dora Bothwell

DORA BOTHWELL, 1950. OIL ON CANVAS.

A deep, lifelong passion for travel defined Dora Bothwell’s life, far more than her art or relationships. A native San Franciscan, she trained as a dancer while a teenager but, following the death of her father in her early 20s, she used a small inheritance to travel to Samoa where she was adopted by a village chief and his family. There, she learn the Samoan language, dance practices, traditional ceremonies and the artistry of the local textile designers and manufactures. For the two years she spent in Samoa, she developed a visual language and art practice that would stay with her for the rest of her life. Incorporating rigorous training and European avant-garde influences, she made work that spoke to the place she was in with insight and reverence but remained recognisably hers. Her art, then, serves as a kind of scrapbook of her travels, a visual record of the way that movement changed, informed, and inspired her. This ‘Keepsake from Corsica’ immediately conjures blue seas and iridescent shells, and the dance of sunlight as it dapples across the land.

Portrait of Ephraim Bueno

REMBRANDT VAN RIJN

For most artists of the 17th century, the oil painting was the final form of any image. Preparatory sketches, drawings, and small paintings were all standard elements of the process, used to refining the composition and formal elements of a picture before taking oil to panel or canvas. This piece, then, is unusual in the canon of art history - an oil painting with a primary purpose of preparation for an etching, a medium at the time that was just over a century old. Rembrandt’s focus here was on the facial features of his subject and the interplay of light and dark. We can see in his rendering of Ephraim Beuno’s hands and garments, composed with loose, thick brushstrokes, that this work was not intended as a finished piece fit for display. Instead, in the delicate rendering of his facial features and the subtle changes in light, we get an insight into the artist at work, working through specific details ahead of a finer, more exacting work in a different medium. Yet, despite it’s function, the work still contains some of Rembrandt’s magic, capturing emotion, dignity, and humanity in oil.

Rembrandt Van Rijn

REMBRANDT VAN RIJN, c.1647. OIL ON PANEL.

For most artists of the 17th century, the oil painting was the final form of any image. Preparatory sketches, drawings, and small paintings were all standard elements of the process, used to refining the composition and formal elements of a picture before taking oil to panel or canvas. This piece, then, is unusual in the canon of art history - an oil painting with a primary purpose of preparation for an etching, a medium at the time that was just over a century old. Rembrandt’s focus here was on the facial features of his subject and the interplay of light and dark. We can see in his rendering of Ephraim Beuno’s hands and garments, composed with loose, thick brushstrokes, that this work was not intended as a finished piece fit for display. Instead, in the delicate rendering of his facial features and the subtle changes in light, we get an insight into the artist at work, working through specific details ahead of a finer, more exacting work in a different medium. Yet, despite it’s function, the work still contains some of Rembrandt’s magic, capturing emotion, dignity, and humanity in oil.

White Squares

LEE KRASNER

As a child in an Orthodox Jewish family, Lee Krasner looked upon the Hebrew texts with awe. Unable to read the language, she nonetheless studied the characters religiously, removing them from their context they took on purely abstract, aesthetic forms. It was this experience that Krasner credits with her lifelong fascination with calligraphy, ancient languages, and hieroglyphics. The rigidity of the structure and evenness of placement within the canvas lend this work a textual feeling. It is communicating a message we cannot read, requiring us to dissasociate the forms from meaning and interpret them purely emotionally. She herself described it as ‘hieroglyphic’, and it was her goal to merge the organic and the abstract together in formalism. The abstraction is clear, but the organic forms emerge as much in the sense of process as the subjects. Shards of yellow, green, and blue emerge out of the dense black background as if stones glistening at the bottom of a sea. We fall into the work, down the rectangular spiral into a natural world, familiar and yet altogether alien.

Lee Krasner

LEE KRASNER, 1948. ENAMEL AND OIL ON CANVAS.

As a child in an Orthodox Jewish family, Lee Krasner looked upon the Hebrew texts with awe. Unable to read the language, she nonetheless studied the characters religiously, removing them from their context they took on purely abstract, aesthetic forms. It was this experience that Krasner credits with her lifelong fascination with calligraphy, ancient languages, and hieroglyphics. The rigidity of the structure and evenness of placement within the canvas lend this work a textual feeling. It is communicating a message we cannot read, requiring us to dissaciate the forms from meaning and interpret them purely emotionally. She herself described it as ‘hieroglyphic’, and it was her goal to merge the organic and the abstract together in formalism. The abstraction is clear, but the organic forms emerge as much in the sense of process as the subjects. Shards of yellow, green, and blue emerge out of the dense black background as if stones glistening at the bottom of a sea. We fall into the work, down the rectangular spiral into a natural world, familiar and yet altogether alien.

J-1952

JAMES BROOKS

James Brooks fought the Second World War with his paintbrush as an official combat artist for the US military, and on his return home, fought a battle with his self through radical, abstract expression. Stationed in Cairo, but deployed across the Middle East and Northern Africa, Brooks would head to the front line of battle, take photographs, and then create paintings, collages, and drawings from these photographs to be submitted to and filed by the military for posterity. The role was not quite that of a documentarian, but it was, by necessity, figurative. So, when he returned to New York and reconnected with his old friend Jackson Pollock, he found freedom and catharsis in distancing himself from the military style of his past. Brooks developed a technique of staining the canvas from the underside, letting the chance operations of thinned oil serve as a basis for his work, and then drawing deliberately atop these stains to create artworks with dual authors - entropy and himself. These painterly accidents provided Brooks with the freedom to explore the repressed and hidden parts of himself in collaboration with a sort of higher power.

James Brooks

JAMES BROOKS, 1953. OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON COMPOSITION BOARD.

James Brooks fought the Second World War with his paintbrush as an official combat artist for the US military, and on his return home, fought a battle with his self through radical, abstract expression. Stationed in Cairo, but deployed across the Middle East and Northern Africa, Brooks would head to the front line of battle, take photographs, and then create paintings, collages, and drawings from these photographs to be submitted to and filed by the military for posterity. The role was not quite that of a documentarian, but it was, by necessity, figurative. So, when he returned to New York and reconnected with his old friend Jackson Pollock, he found freedom and catharsis in distancing himself from the military style of his past. Brooks developed a technique of staining the canvas from the underside, letting the chance operations of thinned oil serve as a basis for his work, and then drawing deliberately atop these stains to create artworks with dual authors - entropy and himself. These painterly accidents provided Brooks with the freedom to explore the repressed and hidden parts of himself in collaboration with a sort of higher power.

The Virgin in Prayer

SASSOFERRATO

In the 17th Century, the Virgin Mary in prayer had come into vogue, aided by the Roman Catholic Reformation that placed personal, solitary worship as one of its central tenets. Wealthy patrons, churches, and religious orders began to collect images of this scene and Sassoferrato, a committed follower of Raphael’s style, became widely regarded as the master of the genre. Looking at this work, one of many that he painted and sold over his life, it is easy to see why. There are no distractions from the subject and the action at hand. The Virgin Mary is framed by a black background, and depicted in three colours: red, blue, and white. He skin is rendered with such exacting delicacy that she seems to come to life, and the lighting offer such clarity as to seem almost hyperreal. For all the technical mastery and compositional genius on show, the star of the work is something far simpler - the Lapus Lazuli blue of her robes. A pigment made from rare stone sourced in contemporary Afghanistan, it brims with life and energy, drawing the eye in and framing the scene with infectious splendour.

Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato

GIOVANNI BATTISTA SALVI DA SASSOFERRATO, c.1645. OIL ON CANVAS.

In the 17th Century, the Virgin Mary in prayer had come into vogue, aided by the Roman Catholic Reformation that placed personal, solitary worship as one of its central tenets. Wealthy patrons, churches, and religious orders began to collect images of this scene and Sassoferrato, a committed follower of Raphael’s style, became widely regarded as the master of the genre. Looking at this work, one of many that he painted and sold over his life, it is easy to see why. There are no distractions from the subject and the action at hand. The Virgin Mary is framed by a black background, and depicted in three colours: red, blue, and white. He skin is rendered with such exacting delicacy that she seems to come to life, and the lighting offer such clarity as to seem almost hyperreal. For all the technical mastery and compositional genius on show, the star of the work is something far simpler - the Lapus Lazuli blue of her robes. A pigment made from rare stone sourced in contemporary Afghanistan, it brims with life and energy, drawing the eye in and framing the scene with infectious splendour.

Arrival of the Normandy Train

CLAUDE MONET

For the last time, Monet lent his brush to the urban, man-made world. Almost every painting Monet was to make after this would be a natural landscape that sung the praises or showcased the power of nature. He had spent the last decade or more paying tribute to a new landscape of Paris, its grand boulevards, metal structures, glass exhibition spaces, and towering bridges, but now all of that modernity had lost its allure. It is fitting, then, that the subject of his swan song to the city and the industrialised world it represented would be this particular train. This was the terminal that linked Paris and Normandy, where Monet honed his en plein air landscapes, and the terminal that took the Impressionists to rural villages north and west of the city to escape and practice. The subject of Monet’s goodbye is the very means of his escape, and he paints it with such tenderness, as it to thank the train itself, or the invention of the steam engine, for what it has provided him: peace, solitude, and a way to connect with himself by connecting to the world around him.

Claude Monet

CLAUDE MONET, 1877. OIL ON CANVAS.

For the last time, Monet lent his brush to the urban, man-made world. Almost every painting Monet was to make after this would be a natural landscape that sung the praises or showcased the power of nature. He had spent the last decade or more paying tribute to the new landscape of Paris, its grand boulevards, metal structures, glass exhibition spaces, and towering bridges but all of that modernity had lost its allure. It is fitting, then, that the subject of his swan song to the city and the industrialised world it represented would be this particular train. This was the terminal that linked Paris and Normandy, where Monet honed his en plein air landscapes, and the terminal that took the Impressionists to rural villages north and west of the city to escape and practice. The subject of Monet’s goodbye is the very means of his escape, and he paints it with such tenderness, as it to thank the train itself, or the invention of the steam engine, for what it has provided him: peace, solitude, and a way to connect with himself by connecting to the world around him.

Inventions of the Monsters

SALVADOR DALI

Spain was in the midst of a civil war, and Salvador Dalí was hiding out in the Semmering mountains near Vienna painting this work, unaware that the city below him was months away from the Anschluss, whereby Nazi Germany was to annexe Austria. “According to Nostradamus the apparition of monsters presages the outbreak of war”, wrote Dalí about this painting, “Horse women equal maternal river monsters. Flaming giraffe equals masculine apocalyptic monster. Cat angel equals divine heterosexual monster. Hourglass equals metaphysical monster. Gala and Dalí equal sentimental monster. The little blue dog is not a true monster.” The canvas is ripe with omens, every inch brings with it foreboding and terror, even in the depiction of the love between the artist and his wife. The great Catalonian, despite his comfort with the subconscious world, was in touch with the frequencies of his culture and in this work he did not invent the monsters, only showed their approach towards a world increasingly willing to have them.

Salvador Dalí

SALVADOR DALÍ, 1937. OIL ON CANVAS.

Spain was in the midst of a civil war, and Salvador Dalí was hiding out in the Semmering mountains near Vienna painting this work, unaware that the city below him was months away from the Anschluss, whereby Nazi Germany was to annexe Austria. “According to Nostradamus the apparition of monsters presages the outbreak of war”, wrote Dalí about this painting, “Horse women equal maternal river monsters. Flaming giraffe equals masculine apocalyptic monster. Cat angel equals divine heterosexual monster. Hourglass equals metaphysical monster. Gala and Dalí equal sentimental monster. The little blue dog is not a true monster.” The canvas is ripe with omens, every inch brings with it foreboding and terror, even in the depiction of the love between the artist and his wife. The great Catalonian, despite his comfort with the subconscious world, was in touch with the frequencies of his culture and in this work he did not invent the monsters, only showed their approach towards a world increasingly willing to have them.

Monologue

JOHN STORRS

An architectural sculptor who, late in his career, began to translate three dimensions into two. John Storrs arrived at a style we would now firmly understand as Art Deco almost entirely independently, predating the widespread consolidation of the movement by nearly a decade. Abandoning his family business and forsaking his inheritance to seek new physical forms in Europe, he studied under Rodin, fraternised with Brancusi, Duchamp, and Man Ray. He translated these ideas and education into sculptural forms that incorporated Native American patterns, Gaelic structures, and Babylonian ziggurats. His work has an architectural eye, and uses the material of American industrialism; steel, brass and vulcanite replace stone in small sculptures that seem to speak to the soaring scale of the skyscrapers he grew up around. Though different in medium, his later paintings manage to bring the same philosophies of sculpture to linen. Interlocking forms and sharply defined colors create a sense of depth and scale that elevates them out of flatness and into a modernist world of dimensionality.

John Storrs

JOHN STORRS, 1932. OIL ON LINEN.

An architectural sculptor who, late in his career, began to translate three dimensions into two. John Storrs arrived at a style we would now firmly understand as Art Deco almost entirely independently, predating the widespread consolidation of the movement by nearly a decade. Abandoning his family business and forsaking his inheritance to seek new physical forms in Europe, he studied under Rodin, fraternised with Brancusi, Duchamp, and Man Ray. He translated these ideas and education into sculptural forms that incorporated Native American patterns, Gaelic structures, and Babylonian ziggurats. His work has an architectural eye, and uses the material of American industrialism; steel, brass and vulcanite replace stone in small sculptures that seem to speak to the soaring scale of the skyscrapers he grew up around. Though different in medium, his later paintings manage to bring the same philosophies of sculpture to linen. Interlocking forms and sharply defined colors create a sense of depth and scale that elevates them out of flatness and into a modernist world of dimensionality.